Jas Obrecht: Jeff Beck the Fusion Years, Part 2 – Keep Your Ears Wide Open or Music Will Pass You By

by Jas Obrecht

Update 1/11/23: We at Line 6 are deeply saddened at the passing of Jeff Beck. He was a hero to many of us, as well as a source of endless inspiration—and we hope that these articles spotlighting a critical period in his musical journey, posted just weeks before his passing, will contribute to the appreciation of his singular legacy. RIP Geoffrey Arnold Beck!

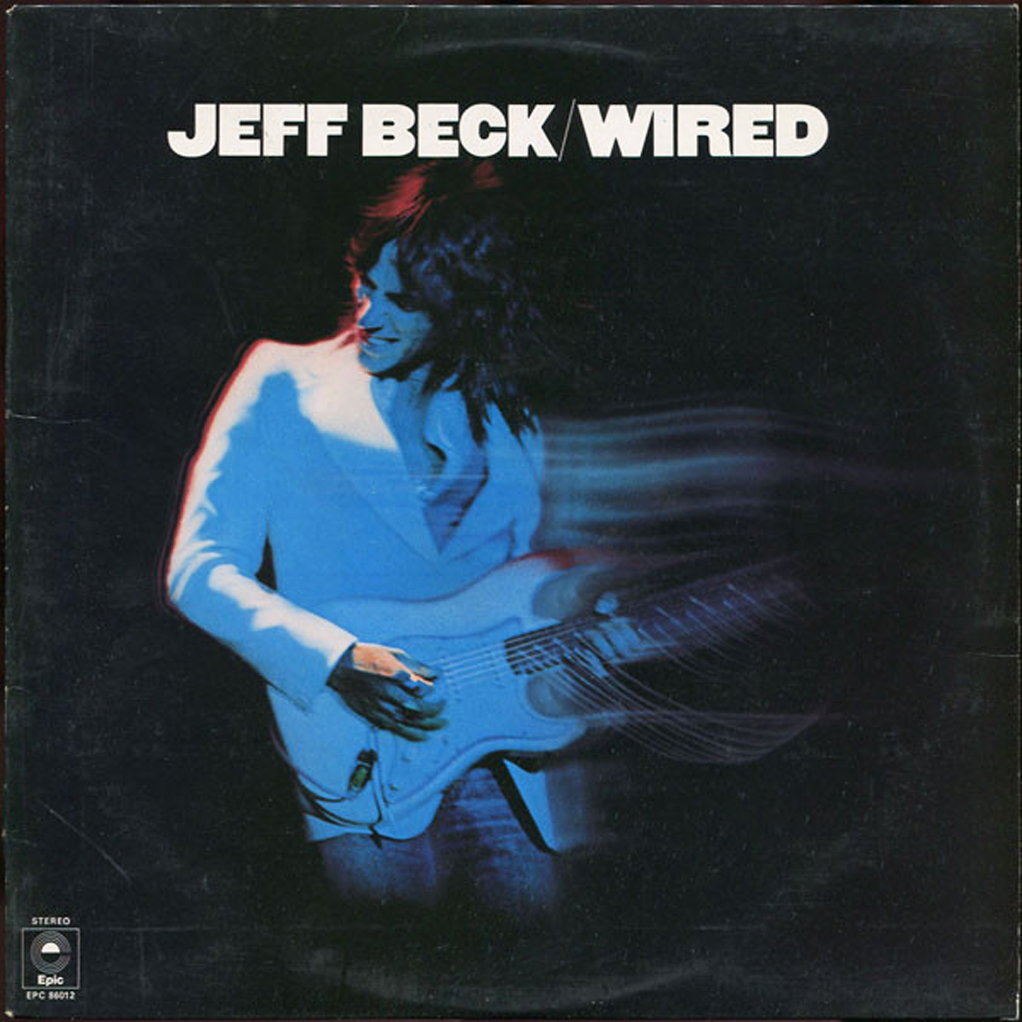

Wired

Beck changed his studio lineup for 1976’s Wired, bringing in Wilbur Bascomb on bass, Max Middleton on clavinet and Fender Rhodes, Jan Hammer on Minimoog synthesizer, and Narada Michael Walden, Richard Bailey, and Ed Green on drums. “I’d listened a lot to Jan with the previous Mahavishnu Orchestra,” Beck explained during our 1980 Guitar Player cover story interview. “He also used to be with Billy Cobham and had played on Billy’s [1973] Spectrum album. That gave me a new, exciting look into the future. He plays the Moog a lot like a guitar, and his sound went straight into me. So, I started playing a lot like him. I mean, I don’t sound like him, but his phrases influenced me immensely. Sometimes I think he plays better guitar than I do! The way Jan used technology really turned my head around and opened up a new world for me. He made me realize that things are always changing and you can’t sit still. You have to keep your ears wide open to hear what’s going on or the music will pass you by.”

Once again, the feedback and distortion that were trademarks of Beck’s early career were largely missing. Instead, he emphasized technical virtuosity and harmonic variety on the eight instrumentals. The group’s jazzy leanings were evident in the funky rhythms and complex chord sequences, but when the tempo and volume cranked up, Beck showcased his blues-rock virtuosity.

The album kicked off with the Max Middleton’s high-energy “Led Boots,” reportedly composed as an homage to Led Zeppelin. Narada Michael Walden wrote four of the LP’s other seven songs: the groove-heavy “Come Dancing”; “Sophie,” which takes listeners on an epic 6:30 journey; the winsome “Play With Me”; and the let’s-chill “Love Is Green,” which featured Walden on piano. On his sole contribution to Wired, Wilbur Bascomb soloed on bass through the first half of “Head for Backstage Pass.”

For most listeners, yours truly included, Wired’s standout track was Jeff’s heart-rending reading of Charlie Mingus’ jazz standard, “Goodbye Pork Pie Hat.” Other tracks featured Jan Hammer’s synthesizer. Some guitar-obsessed critics faulted Wired for the expanded role of the keyboards, which Beck later confessed was accurate: “I probably subconsciously played the keyboards up in order to rule out any accusations that I might be stealing any limelight.” Nevertheless, Hammer’s soaring synthesizer lines and drumming on “Blue Wind” (the only Wired track composed by Hammer and not produced by George Martin) hinted at the direction Beck would take on his upcoming world tour, during which he engaged in nightly solo-swapping with Jan Hammer.

George Martin remembered the Wired sessions as being more challenging than Blow By Blow: “Our first album together, Blow By Blow, was such a big success that in a way it made life difficult for Jeff because he’s not the most secure of people, and he thought, ‘Well, having done that one, how can I follow it up?’ So, Wired became a much more difficult album. Jeff became much more introspective and concerned about it and worried all the time.” Beck acknowledged this conflict in the liner notes to the Beckology box set: “George Martin was a gentleman in every sense of the word. And he was a middleman to stop the musicians from wrangling. It worked really well on Blow By Blow. But by Wired I’d gotten the power bug back again. I wanted more vicious power, but with more concise playing—the way Jan plays, that spitfire thing, a million notes but concise. I wanted to take a chance with Mahavishnu-type blasts. I just lost George with that. ‘I don’t know where the hell you’re going,’ he’d say.”

During a 1978 interview, George Martin was asked about his recording techniques with Beck. Martin responded, “I’m essentially a simple person when it comes to recording, which is not what people believe, but it’s true. I really didn’t do anything special. I think that the sounds that you get are 99% of what you get in the studio rather than what you get in the control room. Of course, you have to use good mikes and good EQ and good studio techniques, but that’s something I kind of take for granted. And with Jeff Beck in particular, the sounds on his guitar had to be up to him, you know? At the outset, I said, ‘I’m not going to give you any magic, if you’re thinking of that. I’m not going to give you sounds that you’ve never had before. The sounds are going to have to come from your guitar and you’re going to have to work on them.’ And we worked on them together, you know. He would make the sounds himself in the studio, and then we would translate them into recording. And, of course, then we would add a little gloss here and there, but there were no particular tricks on the album. The tracks were fairly straightforward.

“I did find that Jeff is an extraordinary person because he seems to have an awful contempt for his guitars. His greatest hobby in life is hot rod cars, and he’s got quite a few of them in his large house down in Kent. And there’s nothing he likes better than to get under his car and change the oil and get himself all greasy. He loves playing about with mechanics and things. And he tends to look upon his guitars like a lump of old iron. It’s amazing to me how he brings in a battered old Fender, says, ‘This bloody thing is no good,’ and I say, ‘Well, haven’t you got another one?’ And he says, ‘No, it’s all I’ve got.’ And then he proceeds to pick it up and make the most incredible, beautiful, heavenly sounds imaginable.”

In his November 1975 Guitar Player interview, Jeff was asked about his amplification and effects during this period: “I’m still using the same wattage output—200 watts. Two Fender speaker cabinets and two Marshall tops. I have the amp miked, though. I used to use Sunn amps with Beck, Bogert & Appice, , but the Marshall tops give you the right sort of gritty sound. The Sunn is a bit too clean. The Fender speakers are a bit more reliable than the Marshall speakers, but the Marshall top is better, I think. I also have a booster and wah-wah. It’s an overdrive booster. It’s just a preamp that distorts, not a fuzz box. It gives you instant power, sustain, and distortion.”

Beck’s 1977 live album was titled Jeff Beck with the Jan Hammer Group. During our first Guitar Player cover story interview, in 1980, I asked Jeff how his views on soloing had changed over the years. He centered his response on the 1977 tour: “Playing with Jan Hammer sort of knocked all the soloing out of me. I mean, a three-week tour, taking exchange solos with a person like Jan can take you to your limit on soloing, so I’ve got no particular desire to play ten-minute solos. Those were never valid anyway, in my book—never! It was just a cheap way of building up a tension in the audience. A solo should do something; it shouldn’t just be there as a cosmetic. It should have some aim, take the tune somewhere. I’m not saying I can do it, but I try and take the tune somewhere. You know, you never get people saying any more, ‘Ah, listen to this guitar solo! Wait till this part comes!’ They talk over it.”

I asked Beck about using the guitar in dialog, such as he did with Rod Stewart’s voice in the 1960s and with Jan Hammer on tour. “That just comes naturally,” he responded. “Sounds corny, but it’s just sort of like putting icing on a cake or holding a conversation with somebody. Really, that’s all you’re doing. You’re saying something through the guitar or whatever it is you’re playing. I just try to say it as clearly as possible, because there’s no prizes for speaking double-Dutch. Nobody can understand you. There’s nothing worse than a boring sermon that you know already, or you don’t know and aren’t interested in. It’s as simple as that, really.”

After his tour with Jan Hammer, Beck stayed out of the public eye and mostly devoted himself to working on his cars. As he explained, “I like the studio because it’s delicate; you’re working for sound. I like the garage because chopping up lumps of steel is the exact opposite of delicate. The garage is a more dangerous place, though. I’ve never almost been crushed by a guitar, but I can’t say the same about one of my Corvettes.

There and Back

Jeff Beck returned to the studio in 1980 for his final pure fusion outing of the era. The core studio band on There and Back consisted of bassist Mo Foster and drummer Simon Philips. Beck was joined on “Star Cycle,” “Too Much to Lose,” and “You Never Know” by Jan Hammer, their musical symbiosis still intact. With one musician pressing notes on a keyboard synth and the other pushing and pulling electric guitar strings, they reached a level in their tradeoffs where their instruments become nearly indistinguishable in shared attacks, bent notes, and tone. During our interview a few weeks before the album’s release, I mentioned this to Jeff. “Oh, great!” he responded. “That’s a compliment. I suppose it’s a similarity in approach, but only mentally. I haven’t got anything like the same setup Jan has. Plus, his is purely electronic, and mine’s guitar. But there is a certain attack on bending the notes and certain basic understandings of the way the tone is. There was no concerted effort on any part to sound the same or dial in any trick thing and make it sound the same.”

The other half of There and Back featured keyboardist Tony Hymas. In “The Pump,” Beck explored his guitar’s vocal qualities, while “El Becko” journeyed from acoustic piano-guitar interplay into a metallic rocker with stellar slidework. “The Golden Road” captured Beck at his most ethereal, and “Space Boogie” provided him the opportunity to push his playing to its screaming limits. “The Final Peace,” the only track composed by Beck, surrounded his bluesy, sensitive Strat lines with Hymas’ lush synth orchestrations.

Asked how he worked out the material for the album, Beck said, “I ripped myself apart, and I ripped Tony Hymas apart. I tried to get him to understand where I was at because Tony came in as an emergency player back in ’78 when we had a tour of Japan lined up and had a problem with another keyboard player. And Tony picked up so quickly and had such a good ear and his musical training and understanding was so superb, I couldn’t see any reason why it wouldn’t be a good idea to start schooling him in my ways. Sounds insulting to say ‘school him’ when he knows more about music than I do, but that doesn’t mean what I’m doing is not valid. In the first two weeks he had already begun to see what I wanted without me saying anything. So, most of the music on There and Back evolved through our playing together. Tony writes everything down. He just scribbles on the backs of pieces of paper. And then when we run through it, I say, ‘Well, here I can’t get along with this framework that I’ve got to solo over. Let’s change that—take this chord out of there and put it somewhere else.’ It’s just custom-building music between us. Of course, if it’s his song to start with, whatever happens to it, it’s still his song. I’ve reached the point where I need to be led somewhere—on a melody level, not so much on the technique or guitar trickery level. The stuff pours out of me when I’ve got the right tune. I can’t help it—it just pours out! But if the tune isn’t right, then I’ve got to push it a bit. If it’s totally wrong, I’ve got to drag it.”

By the time of the There and Back sessions, Beck had pretty much retired his Gibson Les Paul. “You just wind up sounding like someone else with a Les Paul,” he explained. “I think I can sound more like me with a Strat. In fact, I think my Strat was the only guitar I used on the new album. It’s a ’50s Strat. It’s just terrible, but it looks at me and challenges me every day, and I challenge it back. It has the vibrato, and it’s difficult to play. It goes out of tune and all that, but when you use it properly, it sings to you. I’ve had it for two years.”

I asked Beck if he did anything special to stay in tune while using a stock Fender whammy. “I don’t use any special bridge or tailpiece,” he responded. “I like the way Fender makes them. I’ve got it pretty much sewn up now by using a very light graphite on the bridge and on the nut. When the strings rock backwards and forwards and slide lengthwise along the neck, you minimize the chance of a string hang-up over the nut, which is the killer. This can leave you sharp or flat, according to where you’ve left the bar or how you’ve bent the strings. I kept breaking first and second string every single night, and I wouldn’t have it—I just thought there was something wrong here. The string was chafing backwards and forwards back inside the tremolo setup, where it comes out through the block. So, I took a piece of piping—plastic stripped off a piece of wire—and slid the outer casing down the string and put it behind the bridge so that the string was resting in plastic. I never break a string now unless I really, really wind it up. And my action’s pretty high. It has to be because if you have it too low on a Strat, it plunks like a banjo.”

Asked about the rest of his There and Back sound chain, Beck responded, “I’ve got a booster—a modified tiny yellow box that was made by Ibanez. This gives me the same sound on the guitar, but louder. I don’t like to have the tone changed too much because, hey, the guitar sounds great clean! But you want it to sustain and sound the same with a little more volume to it. And I have a Tychobrahe Paraflanger. It’s amazing—I’ve still got basically the same top to the Marshall amp that I had with Rod Stewart. It’s the same chassis, same valves. One or two things may have blown up, but it’s basically the same thing. In fact, some of the valves [tubes] have rusted into their sockets and you can’t take them out!”

Ultimately, I asked Beck, how much does equipment really matter? “It doesn’t really matter. Sometimes you might pick up someone else’s guitar and play a lot more inspired on that because it’s just nice. And yet, having just said that, if you play it long enough and go back on your own guitar, you might be inspired by that. It’s change—variety—that keeps things from kicking over.” Beck, of all people, would know.

Aftermath

Jeff Beck has returned to the instrumental format many times during the ensuing years, such as on Jeff Beck’s Guitar Shop, Who Else, and You Had It Coming. But nowhere does he come closer to the heart of fusion than on Blow By Blow, Wired, and There and Back. In the process, he shattered preconceptions about what rock guitar is supposed to sound like. As Jeff’s website, jeffbeck.com, pointed out, “By merging the attitude and complexity of progressive rock and improvisatory freedom of jazz with intergalactic guitar tones and a sense of humor, Beck opened up the horizon for future guitar instrumentalists like Steve Vai and Joe Satriani.”

Read Jeff Beck: The Fusion Years Part 1.

Thanks to Joe Holesworth for his help with identifying Beck’s fusion-era gear.

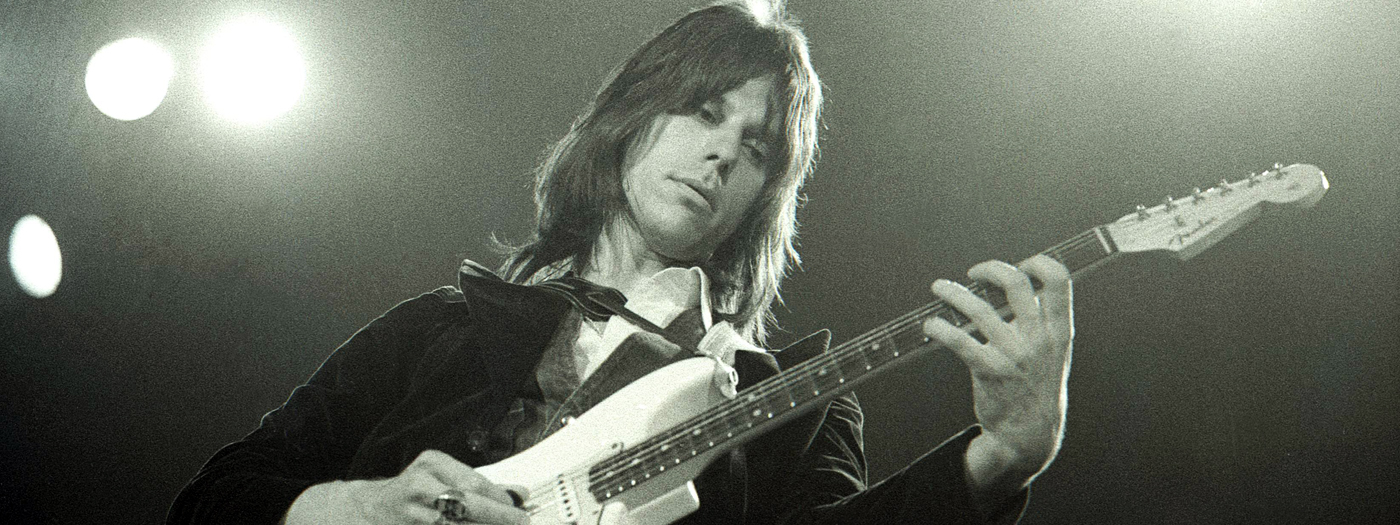

Main photo: Robert Knight Archive/Redferns, Getty Images.

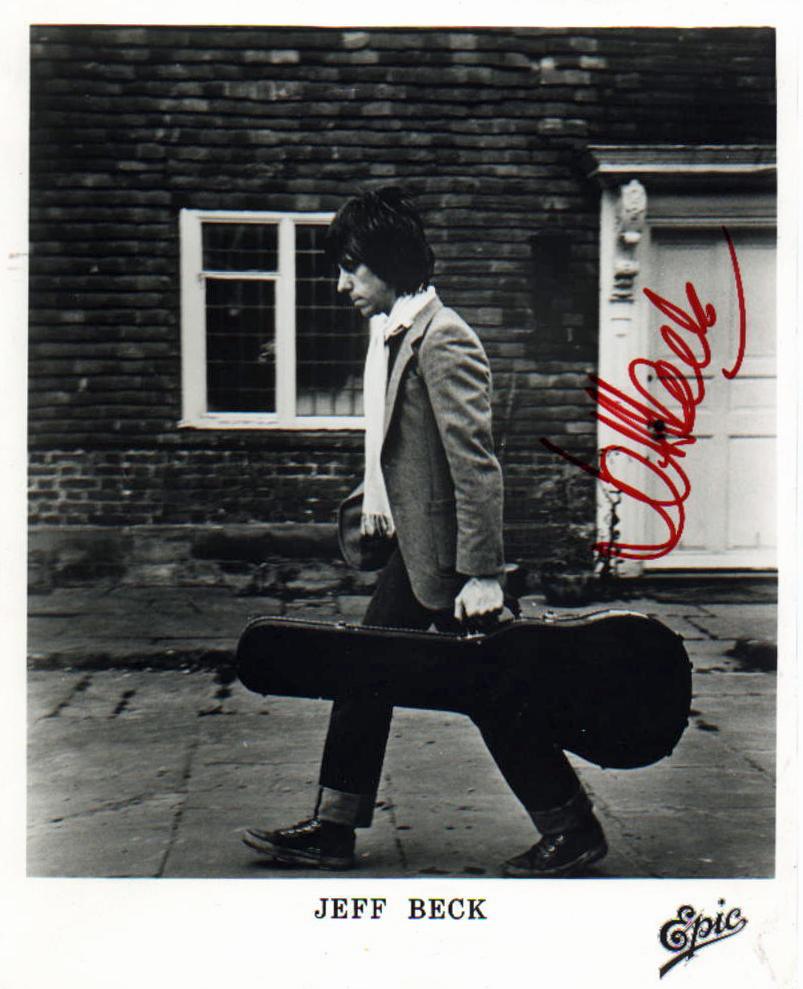

Autographed promo photo courtesy of Jas Obrecht.

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Very enjoyable trip down one of electric guitar’s enduring legends’ memory lane. Jeff Beck’s quotes and the YouTube clips along with all relevant story background bits are golden. Thank you for this blog!