Jas Obrecht: Jeff Beck the Fusion Years, Part 1 – A Guitar Hero Reinvents Himself

by Jas Obrecht

Update 1/11/23: We at Line 6 are deeply saddened at the passing of Jeff Beck. He was a hero to many of us, as well as a source of endless inspiration—and we hope that these articles spotlighting a critical period in his musical journey, posted just weeks before his passing, will contribute to the appreciation of his singular legacy. RIP Geoffrey Arnold Beck!

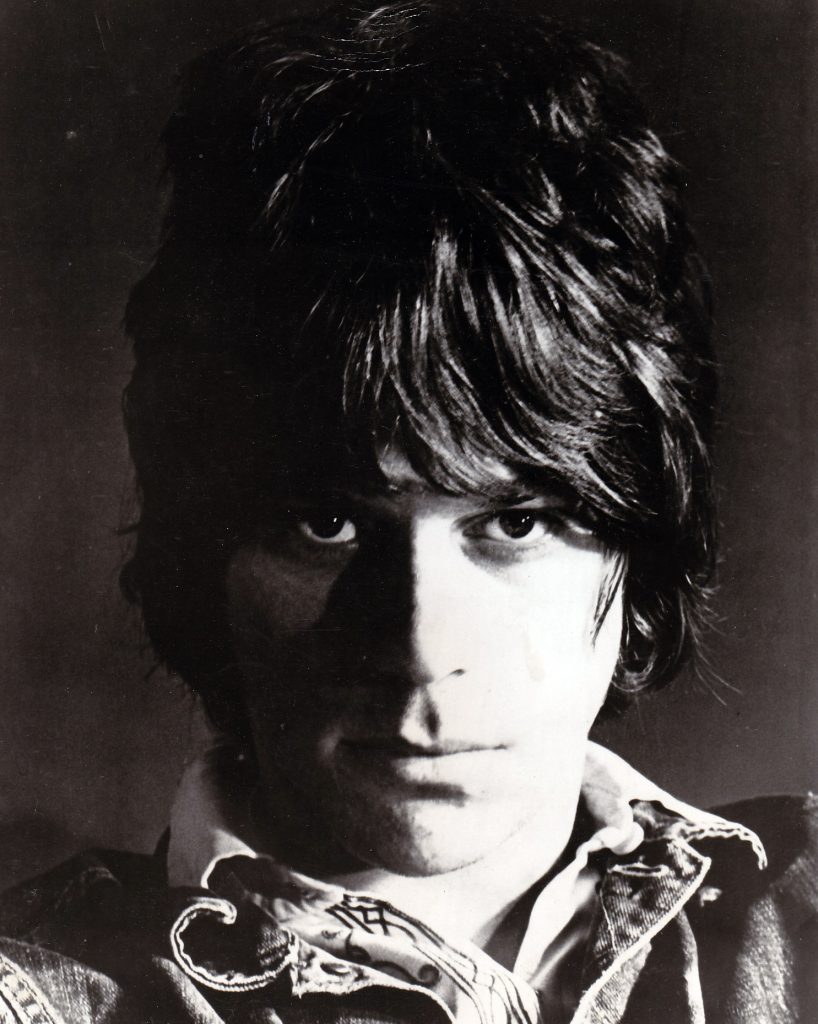

When it came to 1960s blues-rock guitar playing, England’s “big three” were Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, and Jeff Beck. They had all come to prominence with the Yardbirds, with Beck making his first indelible imprint on pop music with the sitar-like hook of “Heart Full of Soul.” Clapton, who preceded him in the band, went on to play in Cream and have a stellar career as a solo artist. Page used his blues-rock savvy, sonic inventiveness, and uncanny sense of the riff and guitar orchestration to fuel Led Zeppelin. While Clapton and Page found wealth and fame by staying close to their blues-rock roots, Beck has continually pushed boundaries, recording everything from bluesy rock and psychedelia to fusion, rockabilly, metal, pop, techno, and electronica.

Besides his stylistic interests, another factor that sets Jeff Beck apart from his peers—then and now—is his unabashed approach to the guitar. From the beginning, Beck has emphasized manual dexterity over the use of sound-shaping devices. As Eric Clapton once quipped, “With Jeff, it’s all in his hands.” Calloused from years of working on car engines, Beck’s workingman hands are capable of precise and powerful string bends far beyond the skill of most players. For greater control of his tone and speed, he typically uses his fingers instead of a pick and continually reshapes his sound by twisting his guitar’s volume and tone knobs. He has an unparalleled approach to the whammy. “I play the way I do because it allows me to come up with the sickest sounds possible—that’s the point now isn’t it?” Beck explained. “I don’t care about the rules. In fact, if I don’t break the rules at least ten times in every song, then I’m not doing my job properly. Emotion is much more important than making mistakes, so be prepared to look like a chump. If you become too guarded and too processed, the music loses its spontaneity and gut feeling.”

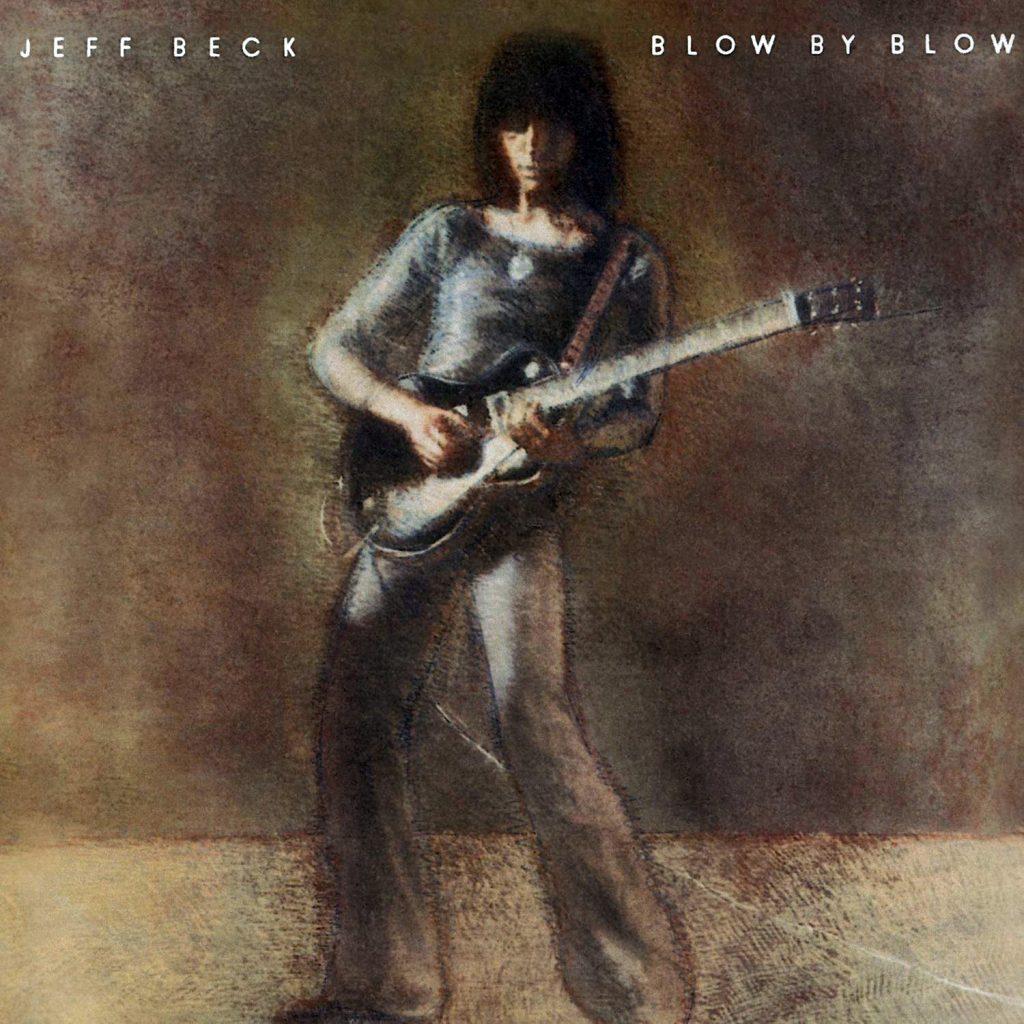

Jeff Beck began his celebrated foray into fusion with the magnificent Blow By Blow album. While this LP routinely makes it onto lists of “The Greatest Guitar Albums,” it was controversial when first released, as was the genre which it represented.

The Birth of Fusion

Exhilarating and innovative instrumental music, fusion first emerged in the United States. Originally, the style was termed “jazz-rock,” since it fused jazz’s improvisational freedom with rock’s rhythms, tones, and energy. As with swing music decades earlier, fusion bands emphasized the soloing prowess of each instrumentalist. Some historians claim its moment of birth occurred in 1959, when Ray Charles played the jazzy Wurlitzer electric piano line in his hit “What’d I Say.” Others point to 1966, when Larry Coryell shook up the jazz world with his band Free Spirits and subsequent work with Gary Burton’s quartet. The Charles Lloyd Quartet, featuring drummer Jack DeJohnette and pianist Chick Corea, was soon playing an exploratory mix of jazz and rock to hippie crowds. Across the Atlantic, Brian Auger was forging jazz-rock hybrids with his band Trinity.

By decade’s end, Miles Davis had become a key influence in fusion, due to his groundbreaking albums Miles in the Sky, Filles de Kilimanjaro, and especially 1969’s In a Silent Way. John McLaughlin, whose spiritual, spidery, spectacular solos were highlights of this landmark album, recalled in Guitar Player magazine, “One would normally think of ‘style’ as something someone picks up and uses, but Miles is the originator of that style. I loved his simplicity, his directness, the authority of his music from a rhythmic, harmonic, and melodic point of view. His conceptualizations were revolutionary. Everything I could see in Miles touched me.” McLaughlin was soon playing clubs with Tony Williams’ Lifetime and recording his first solo albums. He was invited back to play on Miles Davis’ classic fusion albums Bitches Brew, Live-Evil, and A Tribute to Jack Johnson. “Miles was amazing to work with,” McLaughlin recalls, “because he’d never say, ‘I don’t really want that.’ He’d just say, ‘play long,’ or ‘play short.’ Once he told me, ‘Play like you don’t know how to play guitar.’ That’s Miles, and you just go along with it.”

McLaughlin launched the era’s most successful fusion band, the Mahavishnu Orchestra. The original—and, arguably, best—lineup featured Billy Cobham, Jerry Goodman, electric bassist Rick Laird, and Jan Hammer, who was at the forefront of keyboard synthesizer technique in a rock setting. With its furious energy, Indian influences, and mystical jazz, the Mahavishnu Orchestra’s 1971 Inner Mounting Flame album was an immediate success. Their follow-up, Birds of Fire, was even more inventive, with its precise, rapid-fire solos and explosions of musical creativity. The album reached #15 on the charts, but the Mahavishnu Orchestra soon imploded, due in part to disagreements over composer credits. After recording Love Devotion Surrender with Carlos Santana, McLaughlin re-emerged with a new Mahavishnu Orchestra featuring violinist Jean-Luc Ponty. The group’s 1974 Apocalypse album was produced by former Beatles producer George Martin, who’d soon be back in the studio recording Jeff Beck.

Enter Jeff Beck

The Mahavishnu Orchestra’s success set the stage for Jeff Beck’s 1974 Blow By Blow album. Its release surprised many of his fans, since most of Beck’s post-Yardbirds records had been pop and rock oriented. He had briefly tried being a singer on the 1967 single “Hi-Ho Silver Lining,” and then recruited Rod Stewart, drummer Mickey Waller, and bassist Ronnie Wood for the first Jeff Beck Group. “When Rod said he was interested in singing with me,” Beck recalled, “I was genuinely thrilled. I loved his voice. I loved the idea of him singing for my band.” Their chemistry proved electrifying on record and stage, but after the acclaimed Truth and Beck-Ola albums, the group disintegrated in 1969 due to clashing temperaments. While Rod Stewart and Ronnie Wood formed the Faces, Beck put in motion plans to form a new group with former Vanilla Fudge bassist Tim Bogert and drummer Carmine Appice. These plans were scrapped when Beck suffered a fractured skull in a car crash.

In 1971, Beck was ready to play again. Bogert and Appice, though, were committed to a new band, Cactus. Beck formed a second incarnation of the Jeff Beck Group with keyboardist Max Middleton, drummer Cozy Powell, bassist Clive Chaman, and singer Bobby Tench. Lacing Memphis funk with traces of metal and blues, they issued Rough and Ready in 1971 and the Steve Cropper-produced The Jeff Beck Group in 1972. Middleton, in particular, had a profound impact on Beck’s playing. “Max was the first musician I had played with who didn’t make me feel embarrassed that I didn’t know the names of the chords he was playing,” Beck recalled. “He would go through the notes in the chords and I would learn them. That period simmered me down because when you become musically aware to that degree, it’s harder to make a wild rock and roll sound!” Between tours, Beck made a guest appearance on Stevie Wonder’s Talking Book album, playing a brief, jazzy solo on “Lookin’ for Another Pure Love.” His admiration for Stevie’s songwriting would lead him to cover two Wonder songs on Blow By Blow, but first Beck had to express himself in the heaviest band of his career.

With the breakup of Cactus in late 1972, Beck disbanded his group and formed Beck, Bogert & Appice. The power trio first recorded its self-titled album in England, but deemed the sound unsatisfactory and re-recorded it at Chess Studios in Chicago. They then embarked on a much-hyped international tour, which produced the tracks issued on Live in Japan. Attending the trio’s concert in Cleveland, Ohio, I, like many others in the audience, was shocked by the band’s extraordinary volume. My ears rang for days afterward, and I was disappointed by Beck’s reliance on Bogert for many of the solos. It later came out that BB&A’s onstage volume was the start of the serious tinnitus that has plagued Beck for decades.

In an interview during the 1973 tour, Beck expressed his admiration for the Mahavishnu Orchestra: “I try to incorporate dazzling playing into something that at the same time can be commercial. But I can understand Mahavishnu because they’ve already done what I wanted to do, really. McLaughlin is far more technically knowledgeable than me—I mean, I don’t know half of what he knows. I just never had to worry about those kinds of chords, though, because they weren’t usable in what I was playing. McLaughlin wouldn’t come and watch me with the group I have now—let me tell you that!”

Ultimately, Beck says, he was frustrated by the BB&A experience: “I know that Carmen and Tim were frustrated guys, and they wanted me to lead them to new pastures. But we were existing in the wake of bands like Cream and Jimi Hendrix, which made it difficult to find those pastures. We overextended ourselves—we were the answer to the question, ‘What kind of music would these crazed guys make without any chastisement?’” After folding the band in early 1974, Beck went into seclusion for several months. His only major studio appearance—on jazz saxophonist Eddie Harris’ In the U.K. album—hinted at his upcoming move to jazz-rock fusion.

Beck Goes Fusion

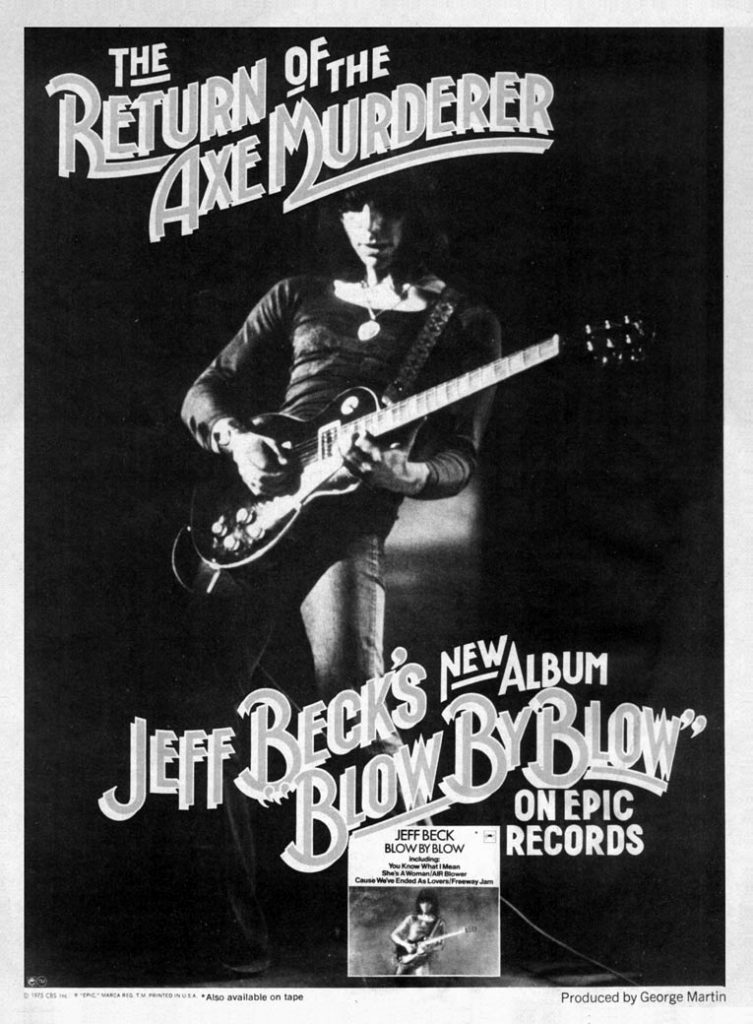

During the summer of 1974, Led Zeppelin seemed omnipresent on the FM airwaves. After BB&A, most fans expected Beck to work in a similar hard rock/heavy metal format. The success of his old Yardbirds bandmate Jimmy Page frustrated Beck: “When Led Zeppelin started doing huge concerts, I was just sitting in my garage listening to the radio. I was like, ‘What’s going on? I started this shit and look at me!’” Consciously deciding not to complete with Led Zeppelin, Beck delved instead into an all-instrumental format. This risky decision paid off with the best-selling and highest-charting Beck album of his career, Blow By Blow.

For the October 1974 sessions at London’s AIR Studios, Beck assembled a stripped-down band with Max Middleton, bassist Phil Chenn, and drummer Richard Bailey. To produce, he chose George Martin, who’d manned the helm for all of the Beatles albums. Martin recalls being surprised when he got the invitation from Jeff: “I’d never worked with him before,” Martin said in a 1978 interview posted on the Gibson company’s website, “but I’d always admired his playing enormously, and I knew his work well. He was always very much a sort of heavy rock, heavy metal guy, but a hip guy—he wasn’t just a basher. But I was quite surprised he approached me because I’d been doing much more soft work, like the group America, than the kind of things he was used to. And for that reason, I thought it was a surprising choice on his behalf. When he did approach me, I was very excited about it. I thought it was a great idea and I looked forward to working with him. In fact, it did work out extremely well.

“Of course, when we started talking about it, the material still had not been formed. And one of the good things about our relationship was meeting up with Max Middleton, who was the keyboard man in the group. He wrote a lot of the tunes with Jeff and a lot of the tunes by himself. It was kind of a three-way partnership, really, because Max had the patience to spend a long time with Jeff, which I couldn’t do, and he was able to translate my thoughts into Jeff’s medium. He was a good go-between between Jeff Beck and myself. The surprising thing for me was that Jeff sort of put up with everything I had to say; there were no arguments at all. He accepted direction extremely well. The idea of putting strings behind his playing was a fairly radical one, and I thought he’ll probably blow his top when he hears it. But he sort of smiled and said, ‘Well, if you say so, it should be alright.’ And when I finished the stuff, he was knocked out with it. He was really thrilled. So, I was quite chuffed about that.”

Beck, in turn, appreciated Martin’s to-the-point input on his playing: “George Martin brought a certain Beatles-like lightheartedness which made it easier to play in the studio. I would be trying to do these really difficult bits and he would say, ‘Jeff, you played like an angel this morning but now you suck. Just take a break!’ I love that because I hate to be patronized about my playing. I like to have input from Joe Public or from someone I respect if they can explain what they don’t like about what I’m doing. What’s lacking in a lot of musicians is that they live in a vacuum in their own little world and eventually the door slams shut and they freeze to death.”

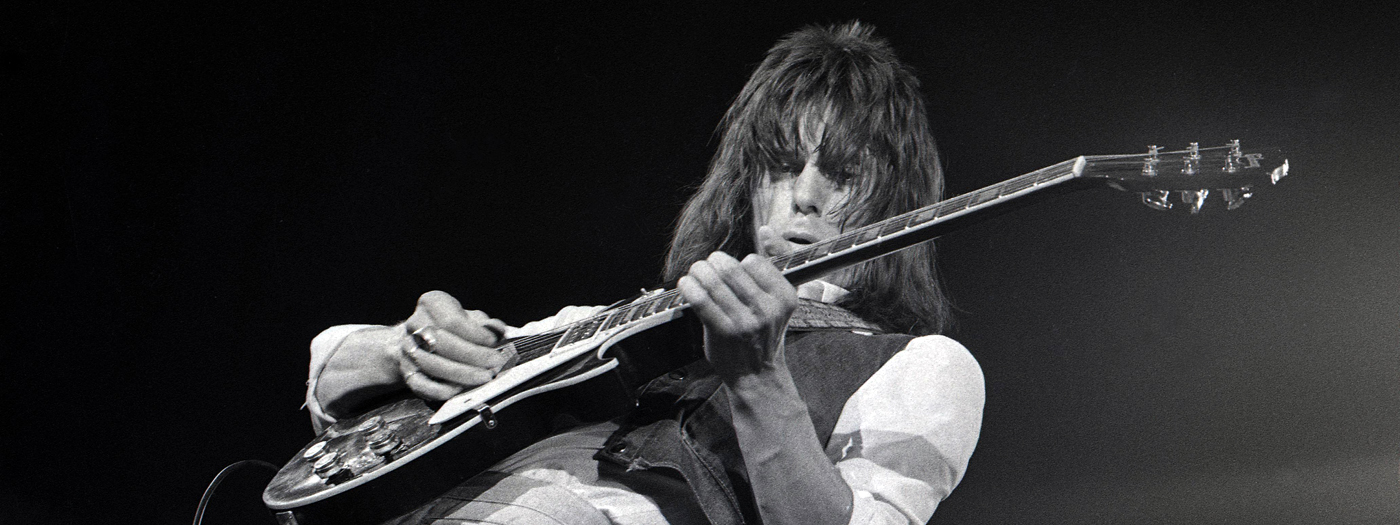

With Blow By Blow, Beck delivered a fusion masterpiece. Asked to describe the music, he said, “It crosses the gap between white rock and Mahavishnu, or jazz-rock. It bridges a lot of gaps. It’s more digestible, the rhythms are easier to understand than Mahavishnu’s. It’s more on the fringe.” With its clipped guitar chords, Herbie Hancock-inspired piano, and multi-tracked guitars, the album’s opener, the Jeff Beck-Max Middleton composition “You Know What I Mean,” clearly announced that Beck was exploring new territory. During his cover of “She’s a Woman,” Beck used a voice box—an invention that had only recently been applied to electric guitar—to approximate the Beatles’ lyrics. “Constipated Duck,” the only track credited solely by Beck, owed as much to Miles Davis’ funkier side as it did to Mahavishnu, and Beck made innovative use of chords during his solos. With its fiery guitar-keyboard lines and high-drama soloing, the Beck-Middleton composition “Scatterbrain” and band-composed “Air Blower” paid tribute to the early Mahavishnu Orchestra. (In retrospect, both of these tracks sound similar to Todd Rundgren’s recordings with Utopia around the same time.)

Beck described the album’s achingly beautiful cover of Stevie Wonder’s “’Cause We’ve Ended as Lovers” as “one of the most beautiful tunes I’ve ever played.” Soloing with warm sustain above Max Middleton’s sparse electric piano, Beck infused the song with volume swells, dramatic bends, and side-of-the-pick harmonics reminiscent of Roy Buchanan, to whom he dedicated the song. With its flurry of trills and raw emotion, the song’s climax was Jeff Beck at his best. Beck followed with another Stevie Wonder composition, “Thelonious,” once again using a voice box. The high drama of “Freeway Jam” provided Beck an on-ramp for whammy-and-Octavia-infused soloing, and brought him an enduring concert staple. (Listening to this track, it’s easy to hear where Steve Morse and the Dixie Dregs derived inspiration.) Beck concluded the album with the lyrical “Diamond Dust,” its orchestral score courtesy of George Martin.

Jeff described his guitar lineup during the Blow By Blow sessions as “late-model” Fender Stratocasters and a 1954 Les Paul Standard with two humbuckers. In this 1974 video, Jeff demonstrates the Les Paul, as well as his effects devices, voice box, Ampeg stage amp, and techniques. (As near as I can tell, the pedals are a Cry Baby wah-wah, ZB Custom volume pedal, and Color Sound Power Boost.)

With its cover painting of a heroic-looking Beck playing the Les Paul, Blow By Blow reached #14 in the pop album charts in April 1975 and went on to become one of the best-selling instrumental albums in history. “Blow By Blow was a major change in my life, really,” Beck told me six years later, “but that was an accident. The album was sort of put together naturally.” In another interview, he described it as “the best guitar playing I’ve done since Truth.”

Jeff took his show on the road, sharing a double-bill with the Mahavishnu Orchestra. John McLaughlin spoke about the tour soon after its completion: “Jeff Beck is number one in that style, a killer. He plays that guitar, man, like nobody I know. We had a lot of gigs together. I had a quartet with Narada Michael Walden, Ralphe Armstrong, and Stu Goldberg, and Jeff had a great band with Bernard Purdie, Wilbur Bascomb, and Max Middleton. And every night we’d get the two bands to finish the gig, and it was great.” Beck welcomed the freedom of fusion, telling an interviewer, “I love jazzing around onstage. There’s no sense in restricting yourself in music. It’s supposed to be there to give you freedom.” On the road, Beck hauled along a box of cassettes and immersed himself in the music of Billy Cobham and Stanley Clarke. He was thrilled when bassist Clarke invited him to Electric Ladyland Studios to play on his Journey to Love album, including on a track affectionately called “Hello Jeff.”

Read Jeff Beck: The Fusion Years, Part 2

Main photo: Robert Knight Archives, Getty Images Redfern Collection

Additional photos courtesy of Jas Obrecht

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Thank you for posting