Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 1 – Earliest Music, First Guitars

by Jas Obrecht

Jimi Hendrix never took formal lessons, learned to read music, or cracked open an instruction book. Yet in the course of four years beginning in September 1966, he established himself as a rock’s most iconic guitarist. What accounted for this phenomenal flowering of talent? Of course, only Jimi himself could have provided the full answer to this question, since much of the essence of creativity comes from within. But through the recollections of those who knew him best, we can uncover the origins of his interest in the instrument and the steps that led to his becoming a transformational musician.

Like Louis Armstrong, Billie Holiday, Bob Marley, and many other musical luminaries, Jimi Hendrix grew up in acute poverty. Born in Seattle on November 27, 1942, he spent most of World War II living with a foster family in Oakland, California, while his father, James “Al” Hendrix, served in the Pacific. Upon his discharge from the Army, Al brought Jimi back to Seattle. He reunited with his wife, Lucille Jeter Hendrix, who’d given Jimi up soon after he was born. For a while the three of them lived together in the Rainer Vista housing project. Jimi slept in the closet. “He’d go in there while Lucille and I were fighting too,” Al recalled in the book we co-wrote, My Son Jimi. “When it came to tempers, Lucille and I were about equalized, and she’d get mad and bang things around. He was old enough to see all the hassles we were having.” Jimi, who hid behind his mother’s skirt when introduced to others, developed a stutter and invented an imaginary friend he named “Sessa.”

Al’s mother, Zenora Hendrix, with whom Jimi was close, had danced in Black vaudeville reviews before World War I. Al, a skilled tap dancer and jitterbugger, had a good singing voice and enjoyed singing at home. Jimi’s interest in music showed up early in life: “He would usually pat his foot to music or bang on pans,” his dad remembered. “Then I got him a couple of sticks and a box to beat on instead of the pans, because he’d knock dents in them. I also made him a little guitar-like instrument out of a cigar box. I cut a hole in the top and sealed the lid to keep it from flopping open, and then I pasted on a wood neck and used elastic bands for strings. He couldn’t get a whole lot of music out of it, but it was a great imaginary piece, and he played a lot with it.” Jimi also had a harmonica, but apparently never learned any songs on it. His next stringed instrument was a ukulele Al found while clearing out someone’s basement.

Jimi’s mother, plagued by alcoholism and other demons, began disappearing for days at a time, sometimes in the company of another man. “I’m quite sure that Jimi was aware Lucille was running around,” Al confessed with sadness, “and it must have affected him. The situation with Lucille always felt like a time bomb.” Al filed for divorce in 1950, and Lucille had four more children with other men. The first of these, Leon, six years younger than Jimi, was the only one to grow up around Jimi. During the 1950s, Al’s financial situation was so dire he occasionally had to leave Jimi and Leon in the care of relatives.

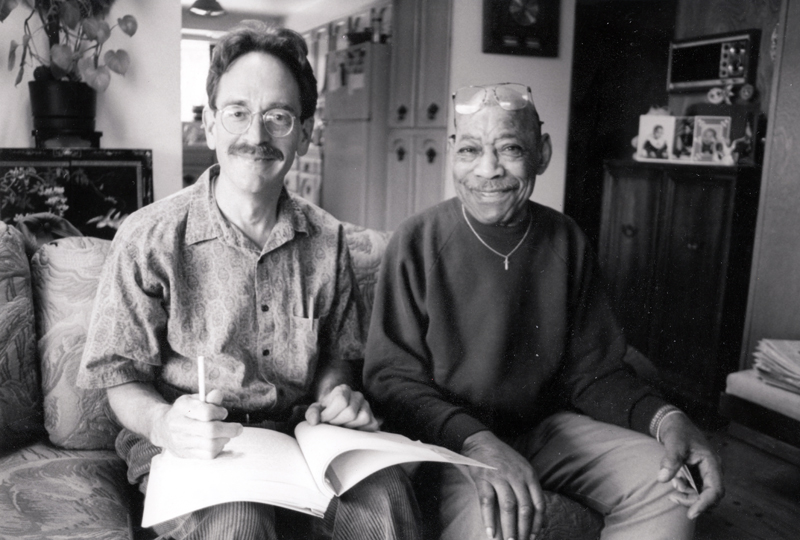

Jas Obrecht and James “Al” Hendrix in 1998.

Jimi Hendrix attended Leschi Elementary School in Seattle. His grade school classmates remember that he wore hand-me-down clothes and shoes with holes in them. He was pigeon-toed, mumbled when he spoke, and was so shy he could scarcely look anyone in the eye. To save money, Al cut Jimi’s hair and fed him horsemeat. Since Jimi never mentioned his mother, even his closest friends assumed she was dead. On Sundays, his grandmother regularly took him to the Church of God in Christ. “I don’t know if Jimi did any singing in church,” Al recalled, “and he was never in the choir that I know of. I don’t know how Jimi did in music at school, either, but I know he didn’t have a voice. He probably couldn’t sing the scales.”

Jimi’s main expressions of creativity before he took up the guitar came in the form of speaking in funny voices and creating artwork. He sketched and painted dozens of scenes of sports events, horses, dragons, cars, World War II battles, knights in armor, abstracts, landscapes, and images of 1950s rock bands performing onstage. Among the artworks Al saved was a notebook-paper sketch Jimi made while staying with his Uncle Frank, Aunt Pearl, and cousins Diane and Bobby Hendrix. Surrounding the image of a young Elvis Presley, acoustic guitar in hand, were song titles in Jimi’s handwriting and spelling: “Rip It Up,” “Don’t Be Cruel,” “My Baby Left Me,” “Love Me Tender,” “Heart Break Hotel,” “Peace in the Valley,” “Blue Suede Shoes,” “Hound Dog,” “I Want You, I Need You, I Love You,” “Parilized,” “Honey Don’t,” “I’m Playing for Keeps,” “Be Bop a Lu-La,” “I Need Your Lovin’,” and “Too Much.” “They had a record player,” Al recalled, “and Bobby remembers that’s when Jimi became really interested in music. Jimi liked to listen to a 45 of Elvis Presley’s ‘Hound Dog,’ and he liked Little Richard’s 45s. When he was around 14, Jimi went to an Elvis concert to see what it was all about. Jimi liked Elvis, so he sketched a picture or two of him.” Elvis’ first appearance in Seattle, the concert Jimi attended, took place on September 1, 1957.

According to Al, Jimi showed no interest in playing the guitar until after his mother’s death on February 2, 1958. At the time, Al and Jimi were sharing a room in a boarding house on 29th Avenue. The most heartrending of all Jimi’s surviving artwork is a drawing of Al, reclining on a couch with his arm over his eyes. Jimi captioned it “Daddy Sleeping” and dated it February 7, 1958, which was on or near the day of Lucille’s funeral. Neither Al nor Jimi attended the funeral, and it’s a profoundly sad work of art. “Oh, Jimi felt sorrow over his mother’s death, and he cried,” Al said as he examined the drawing. “I know her death affected him deeply, but I don’t know what went on in his mind. He might have been a little mad at his mother for living the kind of life she led. Lucille just cut her life short. Who knows—playing guitar could have been his way of working through some of his feelings about his mother.”

Soon after Lucille’s funeral, Al came home and found broom straws on the floor of the single room he and Jimi shared in the boarding house. When asked about them, Jimi replied, “I was sitting there making believe the broom was a guitar.” James McKay, the grown-up son of their landlady, often sat on the porch and played blues on an acoustic guitar, with Jimi listening in. When Jimi told his father he wanted to learn to play, Al purchased McKay’s guitar for five dollars. A lefty, Jimi tried playing the guitar right-handed, then restrung it and flipped it over. Al, who’d insisted that Jimi eat and write right-handed, asked him about it: “Jimi said, ‘I find I can play left-handed easier than I can right-handed.’ ‘Well,’ I said, ‘do your own thing.’ I didn’t even question it. I just let it go on.” From the start, Al said, Jimi concentrated on teaching himself easy riffs, “just like a person plunking away with one finger on the piano. One of the first things that he learned how to play was the theme song from Peter Gunn, so even when he was just starting, he could make music out of the guitar.”

With its easy-to-play, hard-driving hook, Henry Mancini’s “Peter Gunn Theme” was a natural starting place for a beginner guitarist in the late 1950s. Studio guitarist Bob Bain had played the part on a Fender Telecaster he’d modified by installing a humbucker pickup in the neck position and adding a Bigsby vibrato tailpiece:

Even before he began playing, though, Jimi was drawn to blues records featuring heavily amplified electric guitar. During a 1968 interview with Rolling Stone, he revealed that “the first guitarist I was aware of was Muddy Waters. I heard one of his old records when I was a little boy and it scared me to death, because I heard all of those sounds. Wow, what is that all about? It was great.” Jimi picked up other musical influences by tuning in Seattle’s R&B and rock radio stations and from his small circle of friends. “Jimi would pick up a little bit here and there,” his dad remembered, “and he learned a lot of stuff on his own. I never did get him a guitar book or lessons. He liked to play his guitar out in the yard. Sometimes a kid up the street would come down and they’d play music out in the back yard together. He played guitar behind his friend James Williams too, because James wanted to be a crooner. One time before Jimi got a guitar, he and James Williams performed together at a talent show the school put on for parents. They were practicing around the house, working out what they were going to sing – it might have been an Ink Spots tune. They were laughing, because Jimi had taken after his mother when it came to his voice—when Lucille would try to sing, she’d hit all those sour notes.”

Jimi’s former high school classmate, Mary Willix, interviewed dozens of people who knew him during his youth in Seattle. Published in her 1995 book Jimi Hendrix: Voices From Home, an essential reference, these interviews provide a wealth of details about Jimi’s earliest explorations on guitar. Terry Johnson, who was learning the piano and had been friends with Jimi since third grade, described their approach during the months after Jimi got his acoustic guitar: “In the back of our house is a room we call the playroom, where my mom has an old upright piano with a few keys missing. For me and Jimi, it was our sanctuary when we were kids. Jimi had a little turquoise guitar that he’d restrung. Since he was left-handed, he turned the strings around in the opposite direction. He’d tune it up, and we’d start playing. Neither of us could sing, but we’d howl and get enough words out to make the song go along. We played by ear, listening to 45s on that old record player.

“First of all, we learned how to figure out what key the song was in. Then we’d let it play for a while, and then we’d take it off and start all over again. Jimi would listen to the guitar part until he had it figured out and memorized. As rock and roll progressed, Jimi and I started picking out our favorite recording artists. We listened to James Brown, Fats Domino, Little Anthony, and Little Richard. Little Richard was one of the best at that time. He had a lot of piano in his songs, like Jerry Lee Lewis, and a lot of guitar lines, which was the big thing in rock and roll then. So, some of our favorite artists were piano players with guitar backgrounds, or guitar players with piano backgrounds. One of the songs we’d play back in those days was ‘What’d I Say,’ by Ray Charles. Other favorites that we did were ‘Lucille,’ ‘Good Golly Miss Molly,’ ‘Slippin’ and Slidin’,’ ‘Blueberry Hill,’ ‘Long Tall Sally,’ ‘Johnny B. Goode,’ ‘I’m Walking,’ ‘Doin’ the Stroll,’ and ‘Walkin’ to New Orleans.’ Jimi was trying, even then, to find sounds to express what he was feeling. He identified with rhythm and blues guitar players, especially Albert King, Freddie King, B.B. King, and Bobby Blue Bland.

“One of our favorite songs was ‘Let the Good Times Roll’—Earl King, I think—because it had a really neat guitar part in there where Jimi could do the lead and I would come in and do the background. We worked really hard on that one. Later on, I heard that song on one of his albums and I couldn’t help but think it was like a tribute to when we were young kids playing that song. In fact, we would sing it all the way home from school. I’d do the piano with my mouth on the way home, and he’d simulate the guitar part until we got home and did it on our instruments.” Released by King Records as a two-part 45, Earl King’s original version of “Let the Good Times Roll” straddled blues and R&B:

King’s 45 had a lasting influence on Jimi. On August 27, 1968, needing a final track for Electric Ladyland, the Jimi Hendrix Experience recorded fourteen takes of “Let the Good Times Roll” at the Record Plant in New York City. Bassist Noel Redding recalled that they did not rehearse the song in advance, and at least six of the takes were marred by false starts: “Jimi said, ‘It’s in E,’ and we just recorded it. We just played it live and they took it, thank you.” The final take was chosen for Electric Ladyland, where it was retitled “Come On (Let the Good Times Roll).” In this outtake from the session, Jimi extended his solo:

Around 1959 Al found steady employment, and he and Jimi moved to 1314 East Terrace. Their two-room apartment was infested with mice and cockroaches, their neighbors often got drunk, and prostitutes plied their trade in front of the building. “There was very little of anything right about that ramshackle old apartment,” Al said. “There wasn’t any use in complaining about it, though. We just said, ‘Well, we’ll have to live here. This is the best we can do right now.’” Jimi’s beloved dog, Prince, disappeared while they were staying there.

But one fortuitous event did occur while the Hendrixes were living on East Terrace: Jimi Hendrix got his first electric guitar. Al purchased the white, right-handed Supro Ozark solidbody at Myers Empire Music Exchange on 1st Avenue. He also bought himself a used C-melody saxophone. Since the neighborhood was so loud, no one complained when he and Jimi began playing with the windows open. “I didn’t know anything about a sax,” Al explained, “so I was just tootin’ around trying to find the scale. Jimi would tease me that I was playing the same way you’d see a person trying to play piano with one finger—ding, ding. That’s the way we both would do it. We were blasting, though Jimi didn’t have an amplifier. I never did get him an amplifier, although I’d planned on it. But he got music out of his guitar as it was. When he went over to some of those friends’ places, he’d use their amps. He didn’t complain about it.” When Al fell behind in his monthly payments, Myers asked him to return one of the instruments. Al figured Jimi would do more with the guitar, so he brought back the sax.

His Supro Ozark in hand, Jimi began practicing almost to the point of obsession. “Once he got that electric guitar, every day he would be plunking on it,” Al said. “Jimi tried playing lead guitar right away, and he always said, ‘Oh, boy, if I could get to doing it like So-and-so on the guitar,’ and he just worked at it and worked at it, practicing night and day. He played the guitar every day. He carried it around with him at all times, although I don’t believe Jimi ever took it to high school, like some people have claimed, unless they had some special class or event where he needed it.” Leon, who occasionally stayed with Jimi and Al during this time, had similar memories of Jimi’s devotion to his instrument: “He’d wake up in the morning with a guitar on his chest. So, the first thing he’d do in his bedroom, before he’d brush his teeth or take a piss, he’d be playing licks. So, it was inevitable that he would become a master and a maestro one day.”

To hear his guitar amplified, Jimi began visiting the local Rotary Boys’ Club. “They had an amplifier that you could check out,” Terry Johnson recalled. “So Jimi would check it out, plug in his guitar, and hear what he sounded like amplified. Jimi would fool around with amplifiers to create new sounds. In the late ’50s amplifiers had two devices for altering the timbre and tempo of songs—an echo chamber, or reverb, and a tremolo switch. Jimi liked to use the reverb to get a faraway effect.” Overhearing Jimi and Terry practicing, the Boys’ Club supervisors encouraged them to form a band.

Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 2 – Seattle Bands, Betty Jean, and The Blues

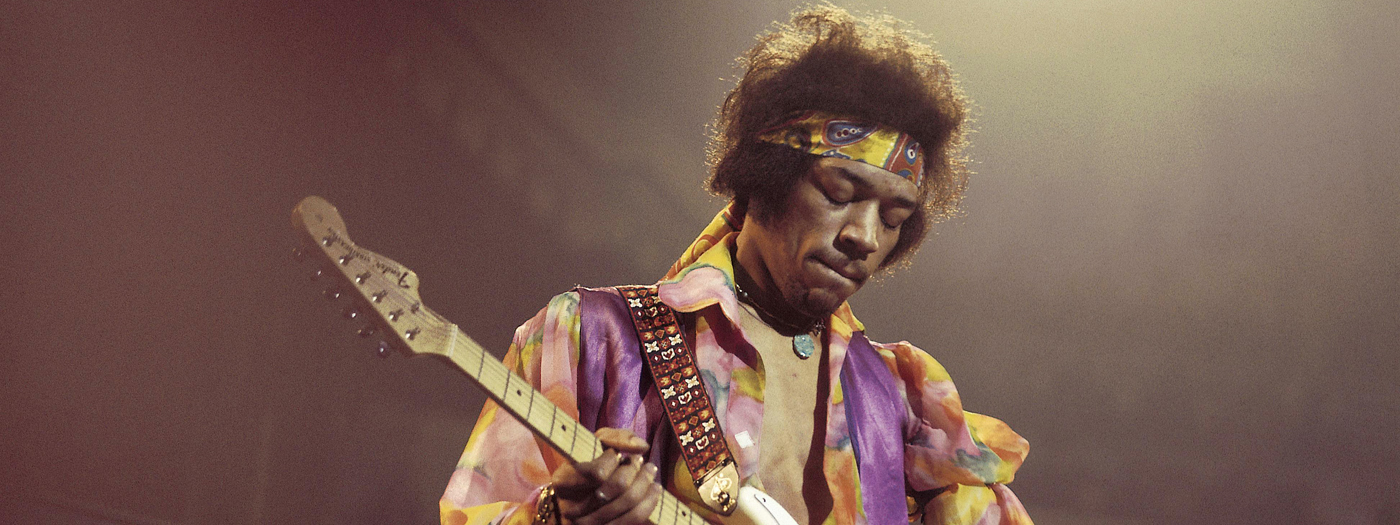

Jimi Hendrix photo: David Redfern, Getty Images Redfern Collection

Jas Obrecht and James “Al” Hendrix photo: Saroyan Humphrey

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

No mention of his time in Vancouver?

So, Jas…if you’re reading this…I’m really interested in how Jimi learned to harness a cranked Marshall.

It seem like one day he was playing R&B fills, and the next, he had totally mastered the raging beast od=f a dimed amp.

Did he go to the crossroads?