Jas Obrecht: Lonnie Johnson – The Most Influential Blues Guitarist Ever

by Jas Obrecht

Whenever you play a bluesy guitar solo with precision, finesse, and unabashed emotion, you’re carrying forward a tradition begun by Lonnie Johnson nearly a century ago. While no longer a household name, Lonnie Johnson was the most advanced guitarist of the Roaring Twenties. Extraordinarily adept at blues and jazz, he left an indelible imprint on the playing of Robert Johnson, T-Bone Walker, Charlie Christian, B.B. King, Chuck Berry, Buddy Guy, and countless others who fell under his spell. In many ways, it’s fair to say that Lonnie Johnson was the originator of modern blues guitar playing.

As John Lee Hooker put it, “Oh, boy! I love that man. He got that style! He’s blues and he’s pop. There’s some of everything, the way he plays it. Oh, I just can’t say enough about the man. He was a genius. And he had his own style too. He didn’t sound like everybody that pick up a guitar. Nobody sound like Lonnie Johnson. You could tell it was Lonnie Johnson every time he picked it up. Oh, he could play a lot of notes, but you know who he was because he had his own style. Everybody loved him—black and white, wherever you are, they loved Lonnie Johnson.”

B.B. King was likewise quick to offer praise: “There’s only been a few guys that if I could play like them I would. T-Bone Walker was one, and Lonnie Johnson was another. I was crazy about Lonnie Johnson…. It took a minute longer to appreciate Lonnie than someone like Blind Lemon Jefferson. Lonnie was definitely a bluesman, but he took a left turn where Blind Lemon went right. Where Blind Lemon was raw, Lonnie was gentle. Lonnie was more sophisticated. His voice was lighter and sweeter—more romantic, I’d say. He had a dreamy quality to his singing and a lyrical way with the guitar. Unlike Blind Lemon, Lonnie sang a wide variety songs. I liked that. I guess he found the strict blues form too tight. He wanted to expand.”

And expand he did! During his first decade as a recording artist, Johnson recorded unsurpassed jazz guitar duets with Eddie Lang, classic jazz with Louis Armstrong and Duke Ellington, delightfully salacious hokum duets with Victoria Spivey and Clara Smith, field-holler blues with Texas Alexander, and plenty of blues, ballads, and pop under his own name. He was a superior singer and prolific songwriter, and endured to have one of the longest careers in blues history.

What made Johnson’s musicianship so striking? For starters, he had a great touch on both 6- and 12-string guitars and an extraordinarily fertile imagination. He could make his instrument thump like a country blues “starvation box” or comp-and-fill like a piano. His crisp rhythms revealed a vast chord vocabulary. His solos provided textbook examples of flawless articulation and superlative string bends. With his brilliant right-hand flatpicking technique and one-of-a-kind left-hand vibrato, he could approximate the sounds of a mandolin or bottlenecked guitar. At his best, his long, beautiful solos conveyed a sense that his hands were hardwired to his very heart and soul. Few guitarists—then or now—have achieved such an instantly recognizable style.

Alonzo “Lonnie” Johnson hailed from the Storyville section of New Orleans. Born into a family of musicians on February 8, 1894, he began on violin and then learned guitar, mandolin, banjo, string bass, and piano. By age 14 he was performing at social events with his family’s string band. His travels around town exposed him to a wide array of styles, including blackface minstrelsy, ragtime piano, brass bands, symphonic orchestras, opera, voodoo chanting, street cries, and especially first-generation jazz and blues. Legendary jazz bassist Pops Foster recalled that “Lonnie Johnson and his daddy and his brother used to go all over New Orleans playing on street corners. Lonnie played guitar, and his daddy and brother played violin. Lonnie was the only guy we had around New Orleans who could play jazz guitar. He was great on guitar. They’d really take off on a number. Lonnie was tough to follow.” For about five years Lonnie played in the French Quarter at the Iroquois Theater and Frank Pineri’s club, which featured blues music.

Lonnie Johnson “Playing With the Strings (1928)

Lonnie was rumored to have travelled to Great Britain with a musical revue during World War I. In 1920 he left New Orleans for good, moving to St. Louis with his brother James. For a while he played violin in a jazz band aboard a Mississippi steamboat. Between voyages, he labored in a steel mill. In search of a better future, he entered a 1925 blues talent contest hosted at the Booker T. Washington Theater. Playing violin and singing, Johnson won week after week, finally capturing the grand prize—an OKeh Records recording contract. In November 1925 he made the first 78 released under his own name. “Mr. Johnson’s Blues” featured the groundbreaking guitar playing and smooth, clear vocal delivery that would become his stylistic hallmarks. On the 78’s flipside, “Falling Rain Blues,” Johnson simultaneously sang and played fiddle.

Johnson’s lyrics on the records that followed often dealt with loneliness, insecurity, and the capriciousness of love and commitment. In Lonnie’s songs, images like gambling, bedbugs, and assorted natural disasters became metaphors for the disillusioned:

“Love is just like playing the numbers,

You got one chance out of a million time,

You’ll put your money on one-ninety-eight, and out pops one-ninety-nine”

Lonnie Johnson “Blues in G” (1928)

Along with his vocal selections, Johnson recorded some of the finest blues instrumentals on record. “Playing with the Strings,” “Away Down in the Alley Blues,” “Blues in G,” and “Stompin’ ’Em Along Slow,” from 1928, are prime examples. Because of the color of Johnson’s skin, his early 78s, like those of Mamie Smith, Rev. J.M. Gates, Louis Armstrong, and dozens of other Black artists, were issued as part of OKeh’s 8000 “race” series. We have no record of how Johnson, a literate, sensitive man who dressed sharply, had wonderful diction, and got along well with record company execs and musicians alike, felt when he saw the blatantly racist ads OKeh used to promote some of his 78s.

With his uncanny skills as a multi-instrumentalist, Lonnie quickly became an in-demand studio guitarist. He backed many singers—Luella Miller, Helen Humes, Bertha “Chippie” Hill, Irene Scruggs, and Alger “Texas” Alexander among them. In jazz circles, he was highly regarded for his guest appearances with Louis Armstrong and His Hot Five. His unusual tremolo and superior string bending on 1928’s “I’m Not Rough” and his exhilarating call-and-responses with Armstrong on “Hotter Than Hot” helped elevate these recordings to “classic jazz” status. Not long afterward, Johnson played his newly acquired 12-string guitar on Duke Ellington’s “The Mooche,” “Move Over,” and “Hot and Bothered,” more than holding his own alongside the great horn men Bubber Miley, Johnny Hodges, and Barney Bigard.

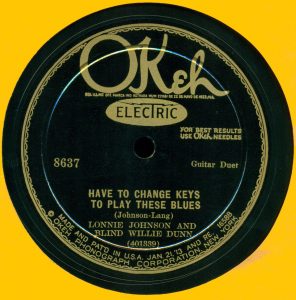

In November 1928 Lonnie Johnson and Eddie Lang recorded the first of a series of guitar duets that would exert a profound influence on jazz guitar, then in its formative stage. The idea to team Lang, a studio sharpshooter who understood harmony better than any other jazz guitarist of the era, and Johnson, who had the finest technique in blues, originated with T.J. Rockwell, artist manager for OKeh Records. Their sparking interplay on selection such as “Two Tone Stomp,” “Have to Change Keys to Play These Blues,” and “A Handful of Riffs” sound as fresh today as on the days they were recorded. To mask the fact that the 26-year-old Lang was white, the labels on the American releases of their original 78s credited him as Blind Willie Dunn. Decades later, Lonnie would remember Lang as “the nicest man I ever worked with. We made many sides together with just two guitars. I valued those records more than anything in the world. Eddie was a fine man. He never argued. He didn’t tell me what to do. He would ask me. Then, if everything was okay, we’d sit down and get to jiving. I’ve never seen a cat like him since. He could play guitar better than anyone I know. And I’ve seen plenty in my day. The sides I made with Eddie Lang were my greatest experience.”

Eddie Lang and Lonnie Johnson “Hot Fingers” (1929)

The onset of the Great Depression sent shockwaves through the record industry. Lonnie Johnson soldiered on, scoring a 1930 hit with “I Got the Best Jelly Roll in Town.” When his recording opportunities evaporated, he labored in a steel mill, toured with the blackface minstrel team of Glenn and Jenkins, and did club appearances in Chicago. Catching the attention of Decca Records, he resurrected his recording career in the late 1930s, when he featured an electric guitar on a smattering of sessions. He then joined the roster of Bluebird Records and scored a major hit with 1942’s “He’s a Jelly-Roll Baker.” Just as his fortunes were on the rise, though, wartime material shortages brought a temporary ban on recording. Johnson went on the road, playing one-nighters throughout the Midwest and West Coast. Most of his income, though, came from outside of music, including a stint as a groundskeeper at a golf course. When recording resumed at war’s end, Johnson first recorded for the small independent Disc label, cutting some of the most lackluster records of his career.

His fortunes changed dramatically in 1947, when he inked a deal with Cincinnati-based King Records. At his very first session, on December 10, 1947, he recorded his pioneering blues ballad, “Tomorrow Night.” Set to piano and acoustic guitar, this tender torch song spent seven weeks at #1 in Billboard’s national Race Records chart. For years afterward it was Johnson’s theme song and a regular on juke boxes and at sock hops. As B.B. King remembered, “When Lonnie sang ‘Tomorrow Night,’ probably his most famous song, I understood that he was going to a place beyond the blues that, at the same time, never left the blues.” Two more Top-10 R&B hits followed: “Pleasing You (As Long as I Live)” and “So Tired.” During his five years with King Records, Johnson recorded dozens more R&B-oriented singles in a variety of formats.

In 1952 Lonnie Johnson became one of the first American blues artists to tour England. These well-received concerts were his last major public performances of the decade. Upon his return Johnson moved to Philadelphia and found work as a janitor at the Benjamin Franklin Hotel. He regularly performed in the community and enjoyed giving lessons to young musicians, but there was little interest in recording his old-school style of blues.

Johnson’s 1959 re-entry into the recording industry came about quite suddenly. Chris Albertson, a deejay at WHAT-FM, Philadelphia’s all-jazz radio station, wondered on air about what had happened to Lonnie Johnson. A caller who knew him, banjo player/guitarist Elmer Snowden, tipped him off to Lonnie’s whereabouts. The Benjamin Franklin Hotel’s maintenance supervisor confirmed that a Lonnie Johnson worked there, but doubted he was the one who’d been a star. But, he told Albertson, “He might play guitar, because he’s real careful with his hands and always wears gloves to protect them.” The moment he set eyes on the janitor named Johnson, Albertson knew he’d found the right man.

Albertson invited Columbia Records producer John Hammond and Riverside Records’ Orrin Keepnews to meet with Johnson and Snowden at his apartment that weekend. Both men showed up. With Albertson rolling tape, the musicians played and swapped stories. “It was an evening filled with amazing music,” Albertson wrote. “Lonnie, the lean man with the misleading, perpetually sad face, looked much younger than his years.” When Hammond and Keepnews passed on recording Johnson, Albertson took the tapes to Prestige Records owner Bob Weinstock, who authorized new recordings. Lonnie Johnson, recording artist, was back in business. “I’ve been dead four or five times,” he smiled, “but I always came back. This time, I knew that someday, somehow, somebody would find me.”

Lonnie Johnson “Tomorrow Night” (1947)

Sessions were arranged, and Johnson cut four well-received albums for Bluesville Records, a subsidiary of Prestige. Laid-back and expertly played, the best of these—Blues & Ballads and Blues, Ballads, and Jumpin’ Jazz—found Johnson and Snowden sharing guitar parts and an easy camaraderie. Johnson also renewed his working relationship with Victoria Spivey, recording Idle Hours and Woman Blues together. The experience inspired his old friend to launch her own label, Spivey Records in Brooklyn. “From 1963 on,” she noted, “Lonnie became practically a house man for my own record company.” The following year Johnson made two 45s in Cincinnati for King Records.

Despite these albums and singles, Johnson did not gain recognition on the scale enjoyed by Mississippi John Hurt, Son House, Rev. Gary Davis, and others who’d recorded before World War II. B.B. King, for one, found this situation disturbing: “As my life went on and my passion for blues grew, it hurt me to see that Lonnie never got the critical acknowledgment he deserved. The scholars love to praise the ‘pure’ blues artists or the ones like Robert Johnson, who died young and represented tragedy. It angers me how scholars associate the blues strictly with tragedy.” John Hammond, son of the Columbia producer, observed that part of the reason for this was that “Lonnie wasn’t playing much blues anymore. He had just been found in a hotel in Philadelphia, and he sang some sweet gospel-type tunes and jazz standards. He’d lost that edge, but every now and then there’d be moments and flashes.”

Lonnie Johnson spent his final years in Toronto. He found regular work at the Penny Farthing, playing a mix of jazz, ballads, and blues. “He was sort of a crossover artist who did everything he did very well,” Jim McHarg observed. “Lonnie was always his own man. He would actually go in front of a blues audience and sing what they might see as a trite, sugary ballad. He would do what he wanted to do and sing what he wanted to sing. He was a free spirit, and I think that’s one of the reasons why Lonnie loved Toronto so much—he was actually accepted as Lonnie Johnson. Not so many people tried to force him into a pigeonhole.”

During September and October 1963, Johnson performed in 17 European cities as part of the American Folk Blues Festival. The roster also included Muddy Waters, Otis Spann, Willie Dixon, Big Joe Williams, and Sonny Boy Williamson. Dressed in a fine gray suit, the dignified Johnson was filmed during the tour, playing a mournful version of “Too Late to Cry” punctuated with an adventurous solo. While he was overseas, Valerie Wilmer, on assignment for England’s Jazz Monthly magazine, asked Lonnie to describe his style of blues. “I am altogether different from the rest of the people that sing,” he responded. “Some of them sing their words like it’s country blues, and some of it is rock ’n’ roll type singing. I sing city blues. My blues is built on human beings on land, see how they live, see their heartaches and the shifts they go through with love affairs and things like that—that’s what I write about and that’s the way I make my living. It’s understanding others, and that’s the best way I can tell it to you. My style of singing has nothing to do with the part of the country I come from. It comes from my soul within. The heartaches and the things that have happened to me in my life—that’s what makes a good blues singer…. I sing blues, ballads, swing—anything. I have to do that in order to keep working ’cause some places don’t like blues and then you don’t have a job. So, whatever’s happening, I keep up with the times.”

In 1965 Lonnie recorded an album for Columbia Records with Jim McHarg’s Metro Stompers, Stompin’ at the Penny. During a visit with his friend Bernie Strassberg that year, he sat down with someone’s electric guitar and was taped playing the remarkable set of blues and jazz songs heard on The Unsung Blues Legend: The Living Room Sessions. He made his final recordings in 1967 for Folkways Records, playing an inspirational array of blues, pop, R&B, jazz standards, and rock-tinged songs and taping a four-minute interview called “The Entire Family Was Musicians.” A lion in winter, Lonnie Johnson, now in his mid-seventies, still sang with feeling and confidence, and he fired off chorus after chorus of supple, perfectly placed solos. For the final track, he ended his recording career right where it had started, announcing into the microphone, “One more blues? Okay. I’ll play you an old one I made a long time ago. I’ll play you the first record I made for OKeh Records, ‘Falling Rain Blues’—that was a big hit.” As the last notes faded, Lonnie Johnson concluded his 42-year recording career. He passed away at home in Toronto on June 16, 1970.

Lonnie Johnson Live “Another Night to Cry” (1963)

In her eulogy in Record Research, Victoria Spivey wrote, “Lonnie Johnson was the greatest blues guitarist man in the business—and what a beautiful blues ballad singer he was too! Everywhere I turn, I hear him in T-Bone Walker, B.B. and Albert King, Muddy Waters, and the younger fellows like Buddy Guy. And, of course, all the white kids are playing Lonnie, most of them thinking they’re being influenced by B.B. What I like about B.B. and T-Bone is that they all give Lonnie the credit for it. I say to Lonnie: ‘Join the heavenly Gabriel as you used to play with the earthly Gabriel, Louis Armstrong.’”

Primary photo: Getty Images/Bettmann Archive

OKeh Records ad: Courtesy Tim Gracyk

Record label photo: Courtesy Roger Misiewicz and Helge Thygesen

Publicity photo from 1927: Courtesy Jas Obrecht

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

nice post!