Jas Obrecht: Stevie Ray Vaughan’s “Texas Flood” Sessions

by Jas Obrecht

During the early 1980s, blues music was in the doldrums. Record sales were down. Even established artists such as B.B. King, John Lee Hooker, and Buddy Guy saw drops in their audiences. Then, with the release of Texas Flood during the summer of 1983, Stevie Ray Vaughan brought blues and blues-rock roaring back to life. In the process, he helped resurrect the careers of many bluesmen. As Buddy Guy reported a few years later, “I owe the biggest thanks in the world to Stevie, because he was sellin’ records and I wasn’t. He opened the door for many of us.”

Vaughan co-produced Texas Flood with his Double Trouble bandmates–bassist Tommy Shannon and drummer Chris Layton–and Richard Mullen, who also engineered the sessions. I met up with Mullen at Austin’s Arlyn Studios in 1996, while he was engineering and co-producing Eric Johnson’s Venus Isle album. During a break, we spoke about the Texas Flood sessions. “Ninety-eight percent of all of Stevie’s records were done straight live,” Mullen explained. “Stevie was relatively fearless in the studio. He was a real performer in the sense that he didn’t think too much about the technical things. Once he got out there and started playing, he was just enveloped in the music. You could see that when he played live, and he wasn’t any different in the studio. If he was into it, you’d see him do his little dance steps all over the studio, just like he was playing for 10,000 people. There were hardly any overdubs at all. Just about the only overdubs were vocals and an occasional rhythm part over a lead, but the basic guitar parts on the studio records were all done live. And they were almost always judged on Stevie’s performance. If someone in the band made a bonk but Stevie played great, we’d say, ‘Well, that’s it. Let’s just go with that.’

“My first record with Stevie, Texas Flood, took us only two hours to record. That’s all we did on that record. It was basically him playing his live set two times straight through. We got in the studio, we set it up, and I said, ‘Just play it like a gig.’ They went through about 12 songs, took a break, and a half-hour later did the whole set again. We basically chose the best of the two cuts, and that was the first record.”

The sessions took place at Jackson Browne’s rehearsal studio in Los Angeles. Browne and Vaughan had met in August 1982, when they’d both played the Montreux Jazz Festival. For Browne, the moment of revelation came when he joined Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble in an after-hours jam session in the Casino bar. “Stevie Ray was just blowing the roof off this small, smoky, after-hours club,” Browne recalls in the Texas Flood liner notes. “It was really exciting. We jammed a little bit, them and the guys in my band. When I heard them play that night, one of the things I said was, ‘If you come to L.A., I’ve got a place set up in a warehouse and you can record.’ It wasn’t even a studio–just a warehouse with a bunch of home equipment. In a way it was a perfect environment because there was no traffic in and out of the place, in a very rough part of the city, and there was kind of a rent-a-cop standing by the elevator so nobody unauthorized would come up into this building.”

That Thanksgiving, Vaughan, Double Trouble, and Richard Mullen loaded up a van in Austin, drove to Los Angeles, and commenced setting up for the sessions. In his 1984 Guitar Player interview with Dan Forte, Vaughan recalled, “The first record, we pretty much set up like we do onstage, but we did have a few baffles between us. We went ahead and used headphones like on one ear. We couldn’t see the control room–it was at the other end of the place with a bunch of stuff in between, and no window. I like it a lot that way.”

Richard Mullen described how they handled the guitar amplification: “I would just have Stevie play and set the amps up myself. We never went through and dinked on the amps like Eric Johnson does. We were more like, ‘Well, this amp either works or doesn’t.’ There wasn’t as much science in it–it was mike it with a 57 [Shure SM-57], turn it on 10, and go. Stevie would usually use as many as three or four amps at the same time. He’d usually have four or five different Dumble Steel-String Singers on hand and six or seven Fender Vibroverbs. On every record, his sound came from a combination of the Fender and Dumble amps–it wasn’t specifically one or the other. We pretty much did all of Stevie’s miking pretty close–within two or three inches of the cone, usually a little off-center. We never did a lot of room miking. We’d usually just add effects afterwards to do whatever room sounds we wanted.” Vaughan reportedly used Jackson Browne’s Howard Dumble-built Dumbleland 300 SL amp for the majority of the Texas Flood session.

In the Forte interview, Vaughan elaborated on his Dumble amps: “Right now, I use a Howard Dumble 150-watt. He calls it the Steel String Singer, I call it the King Tone Consoul–that’s ‘s-o-u-l.’ It’s like an overgrown Fender tube amp.” In those days, between his guitar and amps Vaughan typically had an original first-issue Ibanez Tube Screamer, used for distortion, and three vintage 1960s effects: a Vox wah-wah, a Dallas Arbiter Fuzz Face, and a Tycobrahe Octavia.

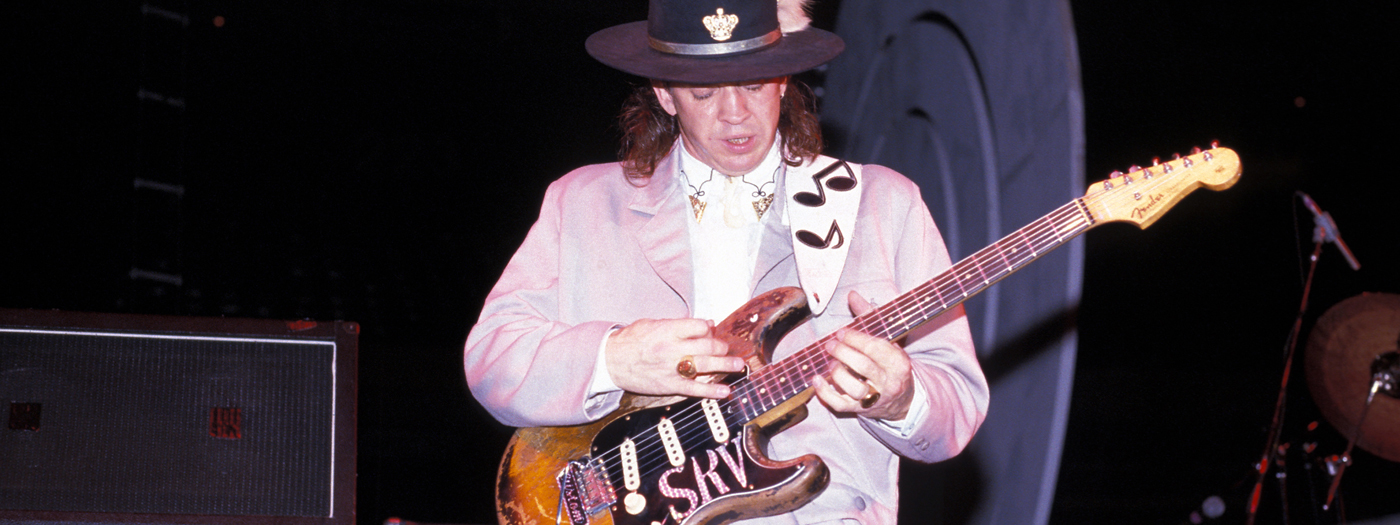

For the beautiful instrumental “Lenny,” dedicated to his wife, Vaughan played the brown, maple-neck Fender Stratocaster that he called “Lenny.” His wife Lenny had given him the instrument, which has been variously described as a 1963 or ’64. But for most of Texas Flood, he used his trademark guitar, “Number One.” In interviews, Vaughan often referred to this beat-up, alder-bodied Fender Stratocaster as “a ’59,” but in fact it was manufactured a few years later. In the liner notes to the Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble box set, guitar tech Rene Martinez explains, “For the record, Stevie always referred to Number One as a ’59. When I opened it up, I discovered ‘1962’ was stamped on the neck and ‘1962’ was written on the body cavity. I thought, ‘Why does Stevie call this a ’59?’ Stevie later told me, ‘If you look on the back of the pickups, ‘1959’ is hand-written on there.’ Ever since he saw ‘1959,’ he started calling it a ’59. The fretboard is a veneer board [curved on the underside], though all of Stevie’s other rosewood-board guitars were slab boards [flat on the underside].”

Except for its 5-way toggle switch and lefty tremolo arm, Vaughan kept Number One stock. Rene remembers Number One’s neck, a Fender D-style, as being the largest he’d ever seen on a Strat. Vaughan used Gibson jumbo frets to help accommodate his heavy guitar strings: “I use a .013, a .015 or .016 depending on what shape my fingers are in, .019 plain, .028, .038, .060 or .056. If I go down to an .018 on the G string, it feels like a rubber band to me.” Like Jimi Hendrix, he typically tuned down a half-step. As Vaughan once explained, “I use heavy strings, tune low, play hard and floor it. Floor it–that’s technical talk.”

In the CD’s liner notes, Tommy Shannon remembers the Texas Flood sessions as being relaxed and spontaneous: “One of the great things about playing with Stevie is he didn’t sit there and tell you, ‘Well, no, play this and play that. Lay out here and . . . .’ You know? Each of us played what he felt, that’s all. And if Stevie heard something and liked it, he could sit down and play it. I think he could hear deeper than anyone else could and it just kind of poured out like water. We knew the songs that we wanted to do when we went into the studio, but no, we didn’t sit down and write out a song list or anything like that. And that’s something we really wanted, to get a live sound on our record.”

Vaughan himself wrote most of Texas Flood: “Love Struck Baby,” “Pride and Joy,” “Rude Mood,” “Lenny,” “I’m Crying,” and “Dirty Pool,” co-written with Doyle Bramhall. He also covered “Testify” (author unknown), Buddy Guy’s “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” and Howlin’ Wolf’s “Tell Me.” The most interesting cover of all, though, is surely the title track, “Texas Flood.” Texas blues singer Larry Davis recorded his original version in November 1958 with Fenton Robinson on electric guitar. Issued on Duke, this original version bears an uncanny resemblance to Vaughan’s, both in the arrangement and especially the vocals:

Following the completion of the Los Angeles sessions, Vaughan and crew headed back to Austin. They added a few vocal overdubs and began shopping the tape. It eventually came to the attention of Columbia Records producer John Hammond, who, having signed Billie Holiday, Charlie Christian, Bob Dylan, and many other musical giants, had one of the most glorious records in the history of recorded music. Hammond, the father of bluesman John Hammond, forwarded the tape to Gregg Geller, A&R man for Epic Records.

In the Texas Flood liner notes, Geller takes up the story: “Over the years John would forward all manner of acts to me. The very last one was Stevie Ray, and that was a no-brainer. I didn’t have to think real hard. What really appealed to me about him was not his guitar playing, which was undeniably brilliant, but his singing was totally natural and believable, not blackface. It wasn’t someone trying to sound real. My decision also had to do with what was going on in music at the time. The idea of electric blues was so unfashionable, but I felt there was a need for what he was doing. There was a need for a guitar hero–the old ones were inactive or doing pop records. I signed Stevie in the spring of ’83. John booked them into Media Sound on 57th Street, and we sat and listened to those original tapes to decide if anything needed to be done, but the gist of our approach was to do as little as possible. There were maybe a handful of overdubs and a slight bit of remixing, and the record came out in June.” Vaughan recalled Hammond being there for the mixdown and remastering.

With the album’s release, Stevie Ray Vaughan and Double Trouble began touring North America and Europe. October 20, 1983, found them at Ripley’s Music Hall in Philadelphia. Barely 150 people showed up for the gig, but Vaughan and band pulled out the stops, delivering a scorching set of Texas Flood tracks, as well as Jimi Hendrix’s “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and an encore medley of Hendrix’s “Little Wing/Third Stone From the Sun.” The show was broadcast live over Philadelphia’s WMMR-FM radio station and later rebroadcast on the nationally syndicated King Biscuit Flower Hour. This set became a welcome addition to Legacy’s Texas Flood reissue.

To those who knew him, one of Vaughan’s endearing qualities was his habit of crediting those who inspired him. In return, many of the musicians he helped bring back into the spotlight expressed their gratitude toward him. As John Lee Hooker said after Vaughan’s death in August 1990, “To me, Stevie’s one of the greatest blues singers there ever was. I am very sad because I wish he were here. But his music will never die. He’s one of the greatest blues musicians that ever picked up a guitar.”

Photo: Larry Marano, Getty Images/Hulton Archive

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

That Thanksgiving, Vaughan, Double Trouble, and Richard Mullen loaded up a van in Austin, drove to Los Angeles, and commenced setting up for the sessions. In his 1984 Guitar Player interview with Dan Forte, Vaughan recalled, “The first record, we pretty much set up like we do onstage, but we did have a few baffles between us. We went ahead and used headphones like on one ear. We couldn’t see the control room–it was at the other end of the place with a bunch of stuff in between, and no window. I like it a lot that way.”