Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 3 – Becoming “The Most Compulsive Player Ever”

by Jas Obrecht

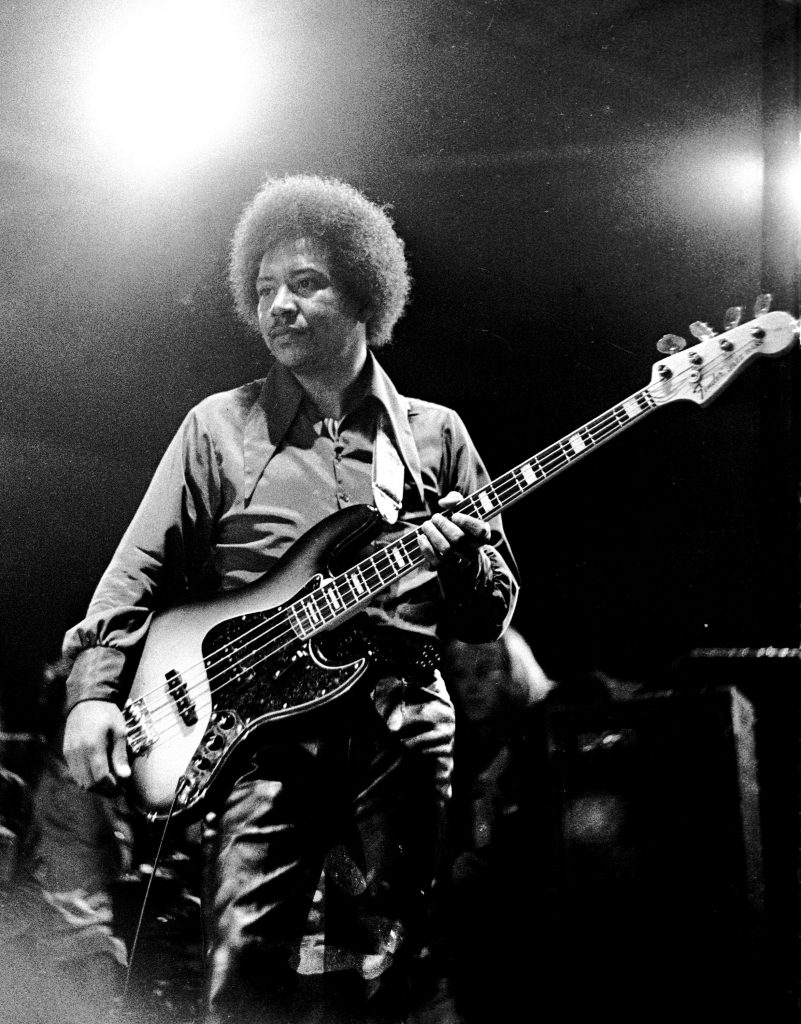

Soon after his arrival at 101st’s paratrooper jump school in Fort Campbell, Kentucky, that November, Jimi met another serviceman, Billy Cox, who would become his lifelong friend and post-Experience bandmate. “I was coming from a theater,” Billy told me in 1988, “and it was raining. We all ran and wound up on the doorstep of Service Club No. 1, where you could rent instruments and go to little practice rooms. I heard this guy playing a guitar with a sound I had never heard before. It was in its embryonic stage, but I knew that sound was destined to be developed into something great. I’d describe it as a mixture of John Lee Hooker and Beethoven. I went in and introduced myself, told him I played bass. I checked out a bass and we started jamming, and that relationship lasted for a long time.”

By this time, Cox recalled, Jimi’s playing was firmly rooted in the blues: “When we first started playing, the only songs we basically jammed on from the very, very beginning were blues songs, because musically we were limited at that particular time as far as repertoire goes. Basically, he was an R&B player—a rhythm and blues player.” Billy recalls that besides Chuck Berry, Jimi’s favorite players to listen to were contemporary bluesmen: “Slim Harpo, especially. Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Howlin’ Wolf, Albert King, B.B. King. He said they were great bluesmen. A lot of songs we initially started playing were by those guys. That was point A. Then we graduated into the Top-40 rhythm and blues, and then into a lot of pop numbers.” In December, Jimi asked Al to send him his red Danelectro Shorthorn. Billy details, “He used that all through the service, up to a year after we got out. When we were making a little bit more money, I co-signed for him and he traded that in and got an Epiphone.” According to Cox, the “Betty Jean” guitar was subsequently destroyed in a house fire.

Military life did not suit Jimi Hendrix. After his 1962 discharge, he sought work as a professional musician, gigging in small clubs around Nashville. Cox and Hendrix became roommates and formed a band, the King Kasuals. At home in Nashville, Billy recalls, they’d often play along to blues records: “We’d sit around, pass the Jell-O or strawberry upside-down cake, and pull out an Albert King or B.B. King record and get a lick or two. I remember those facial expressions Jimi did, because Albert, he just gets out of sight with some of his licks. Jimi really liked that. Albert King was a very, very powerful influence on him. At that time people liked to hear stuff that was current, and Bobbie Blue Bland, Albert King, and B.B. King were very fashionable and popular. Jimi had a lot of influences guitar-wise, but what the world heard of Jimi Hendrix—he evolved into that area because he wanted to break out of all that. You know, we played behind shake dancers and different groups that came to town. Jimi could play ‘Misty’ in the original key, ‘Moonlight in Vermont,’ ‘Harlem Nocturne,’ and stuff like that. So, he basically knew where he was going and how he was going to get there. The other music bored him to a degree, and he wanted to be adventurous and reach for his own individuality in music.”

Jimi’s unwavering dedication to his instrument had its price, socially speaking: “Around this time people nicknamed Jimi ‘Marbles,’” Billy explained, “because he walked up the street with an electric guitar, playing it. He’d play it in the show, he’d play it coming back from the gig. I saw him put 25 years into the guitar in five years, because it was a constant, everyday occurrence with him. People called him Marbles because they thought he was crazy. They couldn’t understand why a man would basically be playing the guitar all the time. But basically, he knew that he had to make this instrument an extension of his body. It was like how people learn to whistle. He learned to play a guitar like a person would whistle, and you have your lips with you all the time, so you can whistle. I remember mornings waking Jimi up, knocking on his door, and there he was laying on the bed with the same clothes he had on the night before, his guitar laying across his stomach or alongside him. He was practicing all night long.”

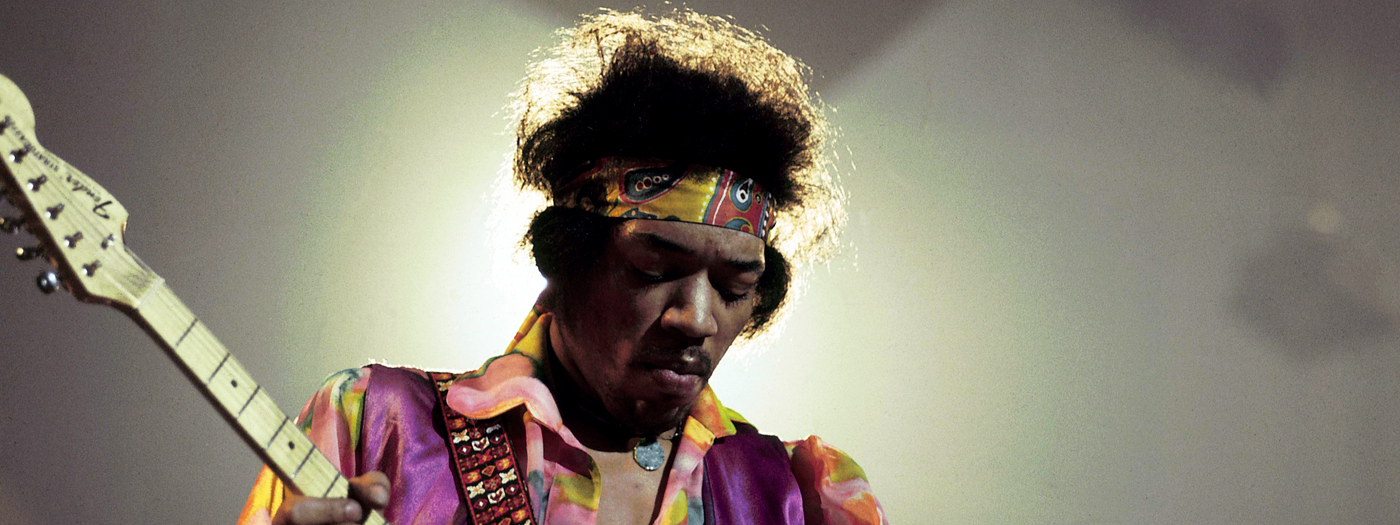

Jimi’s obsessive devotion to the guitar remained constant for the rest of his life. Michael Bloomfield, who had an encyclopedic knowledge of the blues and had played in Chicago clubs alongside giants such as Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf, was among those who witnessed this first-hand. They first met in New York City a few weeks before Jimi left for England to form the Experience. “I remember going to his hotel room,” Bloomfield recounted. “He had a little Kay amp against the wall, and he had his guitar out—immediately he was getting new sounds out of it. He never stopped playing. His guitar was the first thing he reached for when he woke up. We were bopping around New York once, and I said, ‘Let’s find some girls.’ He said, ‘That can wait, there’s always time for that. Let’s play, man.’ He was the most compulsive player I’ve ever run into. That’s why he was so good.

“Hendrix was by far the greatest expert I’ve ever heard at playing rhythm and blues, the style of playing developed by Bobby Womack, Curtis Mayfield, Eric Gale, and others. I got the feeling there was no guitaring of any kind that he hadn’t heard or studied, including steel guitar, Hawaiian, and dobro. In his playing I can really hear Curtis Mayfield, Wes Montgomery, Albert King, B.B. King, and Muddy Waters. And Jimi was the Blackest guitarist I ever heard. His music was deeply rooted in pre-blues, the oldest musical forms, like field hollers and gospel melodies. From what I can garner, there was no form of Black music that he hadn’t listened to or studied, but he especially loved the real old Black music forms, and they poured out in his playing. We often talked about Son House and the old blues guys.

“But what really did it to him was early Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker records—that early electric music where the guitar was hugely amplified and boosted by the studio to give it the effect of more presence than it really had. He knew that stuff backwards—you can hear every old John Lee Hooker and Muddy Waters thing that ever was on that one long version of ‘Voodoo Chile’ [on Electric Ladyland]. He was extremely interested in form—in a few seconds of playing, he’d let you know about the entire structure. That’s why he liked rhythm guitar playing so much—the rhythm guitar could lay out the structure for the whole song. He would say, ‘There is a world of lead guitar players, but the most essential thing to learn is the time, the rhythm.’”

Like Al and Leon Hendrix, Billy Cox, and Mike Bloomfield, Chas Chandler also witnessed Jimi’s extraordinary dedication to his instrument. It was Chandler who’d “discovered” Jimi playing in a seedy New York club, arranged his passage to London in September 1966, and helped orchestrate the meteoric rise of the Jimi Hendrix Experience. While rooming together in London, Chandler recalled, “Jimi used to get up in the morning to go and fry himself a breakfast, and he’d be frying bacon and eggs with the guitar on. That lad never had a guitar off less than eight hours every day, plus the gig at night. He’d take the guitar to the loo with him because he liked the sound of the echo in there. He’d sit in there for hours, just playing a Fender guitar—not plugged in—because he liked the sound coming off the tiles in the loo. He had a guitar on all the time, all the time. He was the best guitarist in the world because he wanted to be the best, and he was prepared to work at it.”

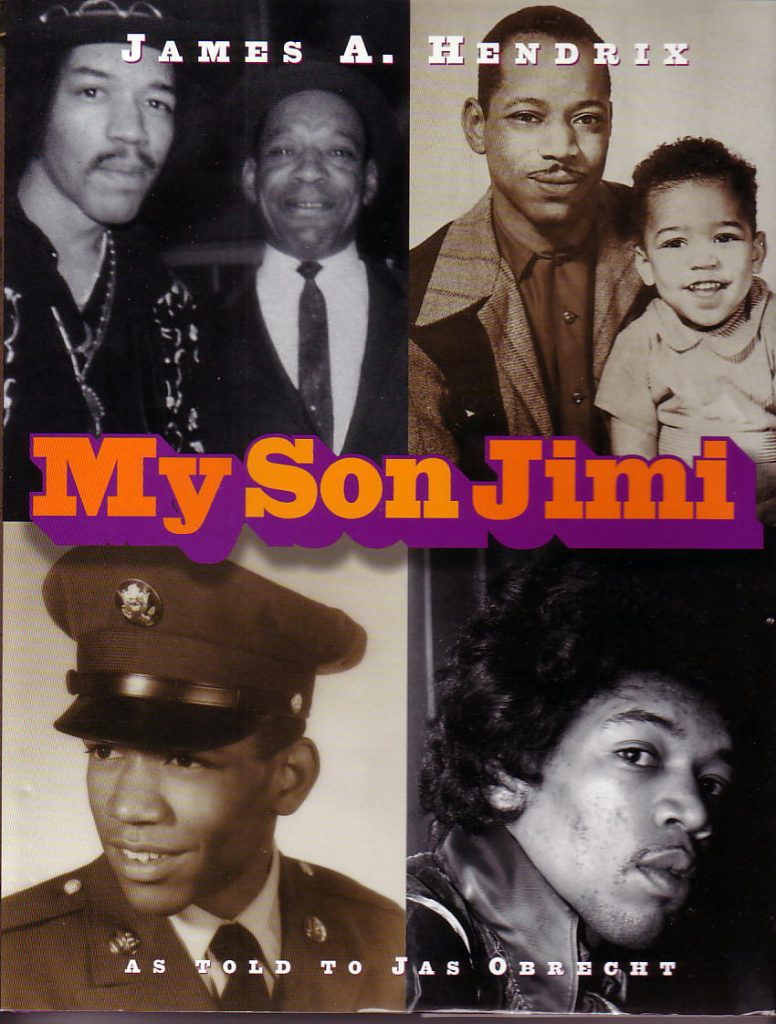

The most savvy music-related advice Jimi Hendrix ever received could well have come from his dad just before he left for boot camp at Fort Ord, California: “It was a Friday afternoon after work,” Al said, “and Jimi told me he was going to make it in music. He was saying, ‘Yeah, dad, I’m gonna be famous one of these days.’ I felt that following the same trend in music that everybody else was doing is a hard trail, so I told him, ‘When you get into the music business, do something original. And if you do come out with something extraordinary, people will take note: “Hey, here’s something different.”’ And that’s sure what he did. After Jimi became famous, I remembered that conversation and thought to myself, ‘Yeah!’”

Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 1 – Earliest Music, First Guitars

Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 2 – Seattle Bands, Betty Jean, and The Blues

Jimi Hendrix photo: David Redfern, Getty Images Redfern Collection

Billy Cox photo: Chris Walter/WireImage, Getty Images

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Very nice and informative article! I didn’t know too much about Jimi’s early days, I’m more in other types of music but for a guitar player there’s no way around Jimi.

He “experienced” the electric guitar as something completely new.

Thanks!