Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 2 – Seattle Bands, Betty Jean, and The Blues

by Jas Obrecht

When Jimi Hendrix launched his first band, one of the first musicians he turned to was his childhood friend Pernell Alexander, who played guitar. They named their fledging lineup the Vibertones, then quickly changed it to the Velvetones. Pernell remembered that “Walter Jones was the drummer, Robert Green played the piano, Luther Rabb played tenor and baritone sax, Anthony Atherton played alto sax, and Jimi and I played the guitar. I think Terry Johnson played with us a couple of times. My dad was our manager. We played all over—at Polish Hall, Washington Hall, the Boys’ Club, and the YMCA.” Robert Green recalled that Jimi and Pernell both played through Pernell’s amp: “They had it down. They got a lot of their fingerwork by listening to Chuck Berry. Jimi and Pernell loved Chuck Berry. We did three of four Chuck Berry numbers—like ‘[Little] Queenie.’ We also played ‘Lucille’ by Little Richard and Fats Domino’s ‘Blueberry Hill.’ We’d play blues for grown-ups and whatever was jamming at that particular time for the youngsters. We played all the pop tunes. We landed a gig at the Yesler Terrace gym and for a couple of months we played there every Friday and Saturday night for teenage dances.”

A friendly rivalry developed between the Velvetones and another local band, the Rocking Teens. “The Velvetones lived in Madison Valley,” Pernell explained. “The Rocking Teens lived up in the Terrace. We all knew each other. In fact, later on Jimi joined the Rocking Teens. Anyway, we were having a North Side/South Side feud. Actually, it was about girls, but the Battle of the Bands was really a serious thing. It would be the Velvetones and the Rocking Kings. We didn’t know about bass guitars back then. Jimi and I would tune our guitars to a low C for the bass part.”

Pernell Alexander pointed to another young Seattle guitarist, Randy Snipes, as the original inspiration for Jimi’s over-the-top showmanship. “We called him Butch. The kid was amazing. He was phenomenal. He had great showmanship. He taught Jimi the stunts. Butch was the first one here to play the guitar behind his back and with his teeth. Jimi learned those tricks from him. Butch taught us both a lot.” Anthony Atherton confirmed this account: “Pernell Alexander and Butch Snipes were the ones who taught Jimi how to play the guitar.” “Jimmy learned a lot from Butch Snipes,” added Luther Rabb. “Sometimes Butch would loosen his strings to play bass. He was fluid. I was amazed by his playing. And if you listened to Jimi and then listened to Butch, you’d hear them playing each other’s licks.”

The next lineup Jimi joined, the Rocking Teens, was renamed the Rocking Kings when some of its older members graduated from high school. They specialized in covers of Top-40 hits: Ritchie Valens’ “La Bamba,” Bobby Day’s “Rockin’ Robin,” the Coasters’ “Yakety Yak,” Bobby Freeman’s “Do You Wanna Dance,” Danny & The Juniors’ “At the Hop,” Chuck Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode,” and Ray Anthony’s “Peter Gunn.” “This was a typical, ordinary, real young teenager band,” Jimi’s dad, Al Hendrix, recalled. “I saw them play, and they made good music.” Looking at a photograph taken of the Rocking Kings at Washington Hall on February 20, 1960, Al identified the lineup as drummer Lester Exkano, sax players Webb Lofton and Walter Harris, and pianist Robert Green. Jimi, wearing the band uniform of white shirt, dark tie, peg-style pants, and powder-blue sports jacket, holds his white Supro Ozark guitar.

Although he doesn’t appear in the photo, Junior Heath also played guitar with the Rocking Kings. “With two guitar players,” Heath explained, “one had to tune his guitar down like a bass, while the other played lead. We’d take turns, going back and forth.” Both guitarists played through Heath’s amp. For a while, Sam Johnson, who lived across the street from the Hendrixes, sat in on electric bass. Walter Harris recalls that the Rocking Kings “played at PTA dances and teenage sock hops, after football games, in the gym, and at the Garfield Funfest. All the schools knew us. We played a lot at Birdland, in the Central District. It was open for kids with no alcohol served until 11:30, when the kids left and the adults came. During the school year we played there on Friday and Saturday nights, but during the summer it was open Wednesday through Sunday.

Jimi Hendrix – A History of his Guitars – Part 1

“There was something unusual about Jimi,” Harris continued. “I felt sorry for him sometimes, like during the summer when he’d be working landscaping with his dad all day and come to practice wearing the same clothes. But, as poor people, we were all in the same situation, trying to express our feelings through our music. It’s just Jimi wasn’t as fortunate in some ways as the rest of us. The first time I went to Jimi’s house, he was living with Al in a little flophouse/hotel on East Terrace. I saw he had a little radio. It turned out that Jimi could play whatever was on the radio. Any number that came on the radio, he could play it. The same key. And he practiced a lot, because the radio was all the company he had. He didn’t have a TV. Most of us were fortunate to have a TV, but all Jimi had was that radio. We’d go to practice and pick Jimi up. He’d leave a note on the table: ‘Dad, I’ve had dinner.’ A cinnamon roll and glass of milk. It was sad, you know. Jimi had no one to cook dinner for him.”

Several other people interviewed in Mary Willix’s Jimi Hendrix: Voices From Home described how Jimi often had to rely on the kindness of others for his meals. All the while, Harris insisted, Jimi kept his cool: “Jimi was a square, like most young kids. Jimi didn’t smoke and he didn’t drink. Jimi was not a fighter. I saw him take verbal abuse, but I never saw Jimi get angry or aggressive toward anybody. Jimi was just a cool, non-violent, lovable guy.”

Another of Jimi’s musical endeavors in 1960 was playing with James Thomas & His Tomcats. Al explained, “Jimi started telling me about James Thomas, who had drums and all kinds of instruments in his home. James was a grown man, but he wasn’t as old as me. He’d get the kids together—ten or fifteen of them—and they’d all play instruments. James was always searching around trying to find music deals, and he also got gigs for the guys at army bases.” According to Al, Thomas would promise to pay his musicians—$15 apiece was the going rate—but that seldom happened. “The guys in the band would always end up with a zero, or maybe even owing James something.” Al laughed at the memory of Jimi accompanying Thomas to a gig in Vancouver and the young musicians having to push the car after it broke down enroute. “After a whole lot of problems, Jimi just said, ‘Man, I’m so disgusted, I ain’t gonna play with these guys no more.’ But each time a chance to play came around, he just couldn’t turn it down. He’d say, ‘Well, maybe this time’s gonna be better.’ Jimi had all kinds of hassles, but he always went back for more.” One of the places Jimi performed at was the Spanish Castle, which Al described as “a roadside stop down on old Highway 99 on the way to Tacoma. Jimi used to go out there and want to jam with some of the groups. I imagine that’s where he got the song title for ‘Spanish Castle Magic.’ I don’t know what the lyrics mean, though—it don’t take a day to get there!”

Al, continually on his son’s case about being responsible, noticed that Jimi started coming home without his guitar. At first Jimi claimed that he’d left it at James Thomas’ house, so Al insisted he go retrieve it. Finally, Jimi confessed that it had been stolen during an intermission at the Birdland. “I got mad because he lied about it,” Al said, “but he was afraid I’d blow up if he told me it got stolen. I said, ‘You’re just going to have to wait to get another one.’ For a few days Jimi was going around with nothing to do, his hands in his pockets, missing the guitar.” Jimi’s Aunt Mary, Al’s sister-in-law, bought him another guitar at Myers Empire Music Exchange, but Al insisted he give it back to her. “I just felt that if I couldn’t get a guitar for him, there wasn’t going to be one. I don’t remember how long it took me to get him another electric guitar—maybe a month or so—but that second electric guitar I got him was the same one I sent to him while he was in the service.” Jimi treasured this red Danelectro Shorthorn, which had a single lipstick-tube pickup. He named the guitar “Betty Jean” in honor of his high school sweetheart, Betty Jean Morgan.

During the summer of 1960, Al began dating Willeen Stringer. Eventually Al and Jimi joined Willeen and her young daughter, Willette, in their house at 2606 Yesler Way. Jimi’s playing reportedly took a quantum leap when Al brought home a stereo record player with detachable satellite speakers. “Jimi would split the speakers apart, put my 45s on the turntable, and play along on his guitar,” Al remembered. “He’d try to copy what he’d heard, and he’d make up stuff too. He lived on blues around the house. I had a lot of records by B.B. King and Louis Jordan and some of the downhome guys like Muddy Waters. Jimi was real excited by B.B. King and Chuck Berry, and he was a fan of Albert King too. He liked all them blues guitarists. We also had a radio and a television on Yesler. I didn’t see Jimi pay too much attention to the radio, but he liked to lay on the floor or sit on the couch and watch TV. Usually when I came home from work, he’d be sitting there with the TV on, and then he’d be playing along to the stereo during commercials. When the program would come on again, he would watch that again.” (Jimi’s passion for records continued throughout his life. At the height of his fame with the Experience, he had a collection of close to a hundred albums, including several each by Muddy Waters, Lightnin’ Hopkins, John Mayall, and Bob Dylan.)

Two of Al’s Muddy Waters 45s—“I’m Your Hoochie Coochie Man” and “Rollin’ Stone,” both issued by Chess Records—left such a lasting impression that Jimi played the songs throughout his career:

In addition to Muddy’s virile, no-notes-wasted approach to the guitar, Jimi was influenced by the Chicago blues great’s singing style, perfectly exemplified by “Mannish Boy”:

A half-dozen years later, as the Jimi Hendrix Experience played their first gigs in London, British blues fans were quick to notice the similarities. As John McLaughlin noted, “Jimi was singing like Muddy Waters. Jimi had that thing, had the sound. It was almost part talking, part chanting. And he had the timbre, that sound that Muddy’s voice had. So, by the time he hit, people were just like, ‘Wow, Jimi, beautiful!’” The Experience recorded live versions of “Hoochie Coochie Man” and “Rollin’ Stone” (renamed “Catfish Blues” in a nod to its opening line) for the BBC. In concert, Jimi easily displayed his mastery of the stop-time pacing of “Rollin’ Stone,” and then rocketed into space, figuratively speaking, with jaw-dropping extended solos highlighted by perfect string bends and machine-gunning chordal passages:

Jimi spent his final months in Seattle living with his dad and the Stringers on Yesler Way. After he dropped out of high school, he was unable to find work in a grocery store or hotel, so Al put him to work mowing lawns and doing other landscaping tasks. In May 1961 Jimi wound up in Seattle’s juvenile hall. According to Al, Jimi had been arrested for joyriding in a stolen car. Upon his release, Jimi enlisted in the U.S. Army’s 101st Airborne, a.k.a. the Screaming Eagles.

Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 3 – Becoming “The Most Compulsive Player Ever”

Jas Obrecht: How Jimi Learned to Play Guitar Pt. 1 – Earliest Music, First Guitars

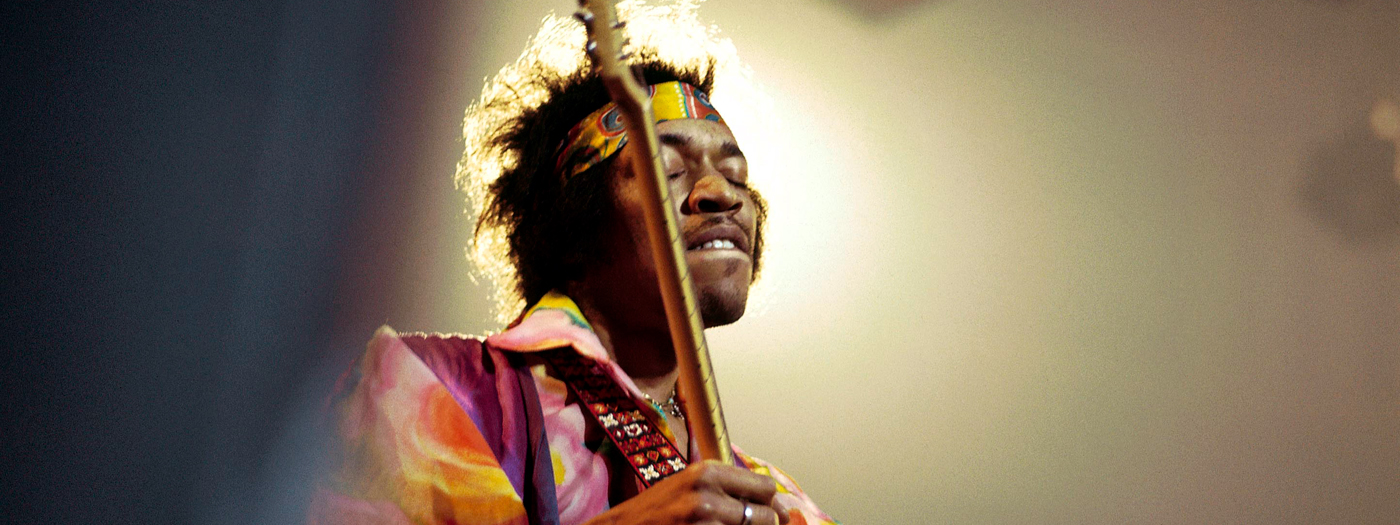

Jimi Hendrix photo: David Redfern, Getty Images Redfern Collection

A longtime editor for Guitar Player magazine, Jas Obrecht has written extensively about blues and rock guitarists. His books about music include Rollin’ and Tumblin’: The Postwar Blues Guitarists, Early Blues: The First Stars of Blues Guitar, Talking Guitar, and Stone Free: Jimi Hendrix in London. For more of Jas’ writing, check out https://jasobrecht.substack.com.

Related posts

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.