Carol Hatzinger – From Recording Revolutionary to Senior Director

by Barry Cleveland

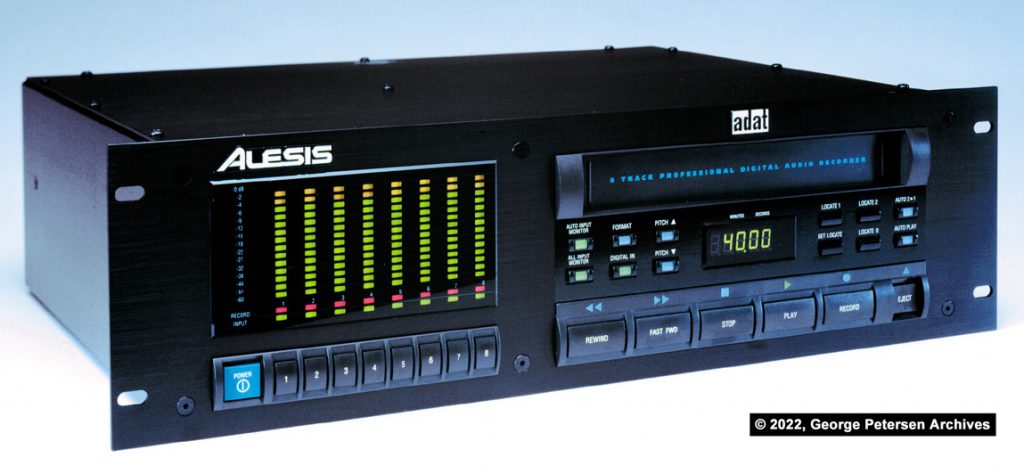

The ADAT (Alesis Digital Audio Tape format) recorder began arriving at retailers 30 years ago this month. The ADAT, which recorded eight tracks onto an inexpensive S-VHS cassette, sparked a recording revolution that resulted in the emergence of countless “project” and home studios in which commercial-quality recordings could be made for a fraction of the cost of recording in pro facilities (something typically only possible for bands and artists signed to large record labels). This, in turn, led to the proliferation of independent record labels, and ultimately to the fact that nearly all musicians today have at least a modest home recording setup. And while the ADAT era has long since passed, the multichannel ADAT Optical Interface or “lightpipe” remains a standard that is still used to this day.

The core engineering team responsible for the ADAT was Marcus Ryle, Michel Doidic, Keith Barr, Alan Zak, Dave Brown, Carl Lafky, and Carol Hatzinger (Carol Nakahara at the time). Hatzinger was also directly involved in the development of other Alesis products, as well as products by Fostex, Studer, Dynacord, Steinberg, and Leprecon. She was a founding member of Line 6, and currently serves as the Senior Director of Project Management. Women’s History Month is a fitting occasion to spotlight this largely unheralded frontline revolutionary and now principal executive.

“It was obvious to us that Carol was an exceptionally talented and brilliant engineer from our first meetings, and we worked hard to convince her to join our team,” says Ryle. “She played a vital role in the development of the ADAT, writing every single line of code in the original unit, and virtually all of the code in the BRC [Big Remote Control] and RMB [Remote Meter Bridge], as well as designing significant parts of some of the custom chips. And, of course, she also made many more technical contributions to other products over the years. Thank you, Carol, for helping to change the recording world!”

The original “black face” ADAT recorder.

Talk a little bit about your family background.

I was born in Seattle, third generation Japanese, also known as Sansei, which means that my grandparents immigrated to the U.S., but my parents were born here. So, I grew up very American, but with a lot of the cultural aspects of being Asian-American. In many ways I epitomized the stereotype: quiet, studied classical piano, good at math, excelled in academics. My father had high expectations and so I got straight As throughout my schooling, but not because I was so smart. I worked hard because not doing so was not an option. There’s an episode of Glee in which two Asians are talking and one says that they received a B- and the other acknowledges that as an “Asian F.” Well, that was my life.

Do you speak Japanese as well as English?

Unfortunately, language was not one of the things that was passed down. I grew up knowing various words and simple phrases as a kid, but not enough to have a conversation. Most of my generation weren’t taught to speak Japanese, likely because of the war. My grandparents and parents were removed from society with whatever they could each put into a single suitcase and forced to spend three years of their lives in the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho, where they were surrounded by barbwire fences and armed guards. So I believe that when my parents’ generation had children, they wanted them to be thoroughly American.

What were the circumstances that led to your becoming an engineer working within the music industry?

Well, I love music, and playing piano and singing were my outlets—but in my family music was a hobby and not a career. I was really good at math, so I looked to see how I could apply that skill. My uncle owned a chain of music stores throughout the Seattle area, and every year he would go to the NAMM Show in California. I attended my first NAMM Show in the late ’70s, when it was held at the Disneyland Hotel, and that’s what triggered me to think about how I might combine my love of music with something “practical.”

I entered college as an electrical and computer science engineering major, but I also auditioned for the music department and was accepted as a music major. I never declared it as a major or minor, but I did take several music courses for fun. So, yeah, I entered college with the goal of being able to connect music and engineering, though I had no idea what that might look like in terms of a career.

What kind of music were you playing?

I was trained as a classical musician and learned a lot of music theory, which made it fun taking the college classes and studying things like composition. But for fun I also really enjoyed pop, R&B, and other more contemporary music.

Engineering at that time was considered by many to be mostly a male profession. Did you encounter any difficulties as a woman, and in particular an Asian-American woman?

I think I had a pretty healthy attitude about being a female Asian-American. It’s who I am, so I couldn’t really change that even if I’d wanted to. There were very few other females in my engineering classes, and sometimes I was the only one—but I worked hard to prove that I was just as capable as any male in class and made sure I was not viewed as the weak link, especially when working on any group projects. I also didn’t have a chip on my shoulder about any of that, so I didn’t go into the classes looking for problems. My dad taught me at an early age to just ignore people who make disparaging remarks about ethnicity or anything else. All that said, I don’t recall experiencing any discrimination in college. I know that’s not been everyone’s experience, but all the males I worked with were great. I feel very fortunate in that regard.

The Alesis Big Remote Controller or BRC.

Circling back to getting started working as an engineer in the music industry, what was the environment like at the time?

Based on what I had seen at the NAMM Shows, I knew there was a connection between music, math, physics, electronics, and programming. In fact, one of my senior papers was titled The Application of Computer Science and Engineering to Music Synthesizer. At the time, engineering jobs for larger companies such as Yamaha and Roland were all in Japan, and U.S. companies were all quite small. Although my first job out of college was actually in aerospace at Northrop, I sent my resume to some music companies, Oberheim being one of them.

Apparently, it made a favorable impression.

I was living with my parents at the time and when I came home one evening my mom told me there was a message from Tom Oberheim. And I was like, “Wow, not some HR person, but the Tom Oberheim.” I interviewed and joined Oberheim in September, 1986. I’d gone from working with a company of thousands of people that had to have security clearances, to working for a company that at the time had less than 100 employees. I had no idea what I was in for, but I thought, “Hey, this is what I wanted to do and this is really cool.”

What exactly did you do at Oberheim?

My first project was the DPX-1 Sample Player, which could play back samples from the E-mu Emulator II, Sequential Circuits Prophet 2000, Ensoniq Mirage, and Akai S900 samplers by loading 3.5″ and 5″ floppy diskettes. A team of five engineers, all male, had already started the project and had designed an operating system and an audio engine that could accept the various formats, grab the information from the diskettes, and then process it to reproduce the sampled sounds. My first job was to analyze the Emulator II, determine what all the data is and where it exists, then figure out how we could play the sounds back using our general voicing engine. That isn’t the sort of thing they teach you to do in school, so it was like being a technical detective—but I love that type of stuff and I was really motivated to do well. Plus, it was a lot of fun! There was also a series of compact mini performance products that I worked on, but I was only there for a couple of years before I transitioned to Fast Forward Designs.

What was Fast Forward Designs?

Fast Forward Designs was a company run by two extremely talented engineers named Marcus Ryle and Michel Doidic, who had previously worked at Oberheim, but left to form their own consulting company. At the time, they had recently designed the Alesis HR-16 High Sample Rate/16-Bit Drum Machine and MMT-8 Multi Track MIDI Recorder, both of which were huge hits. An engineer at Oberheim introduced me to them in January, 1988, and by July I was working for them. I’d gone from a company with thousands of employees to one with less than 100 and was now one of six people total, five of whom were engineers.

ADAT team members (left to right). Top: Alan Zak, Craig Devin, William McGee, Carol Hatzinger, Russell Palmer, Marcus Ryle.

Bottom: Dee Jordan, Carl Lafky, David Douglass.

What were some of the most important products you worked on?

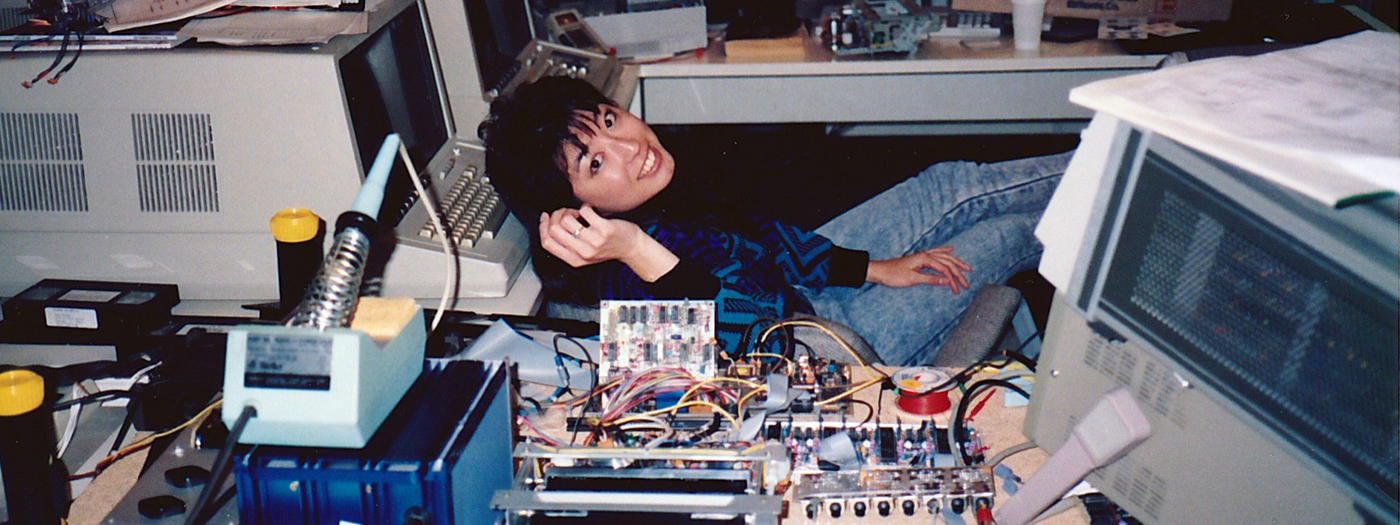

My first projects were the Leprecon LM-850 56-channel MIDI lighting controller and the Alesis DataDisk, but the most challenging and exciting projects were for the Alesis ADAT recorder and that whole family of products. I wrote all of the code and designed significant parts of many of the custom chips for the original “black face” ADAT machine, as well as code for the BRC and RMB. Those were obviously truly revolutionary products and it was amazing to be part of such a smart and innovative team. Also, all of our work was kept highly confidential and we weren’t allowed to talk about it with anybody, much like when I was working in aerospace—but this was way more exciting because of my personal interest and because it was for the music industry.

I imagine the tools you had at your disposal were quite different than those available now.

Absolutely. It was crazy. For example, I recall using copy and paste in MacDraw to create timing diagrams to figure out how the signals needed to line up to do what was required [laughs]. We did have some fancy workstation software, though, to run simulations of the designs before we committed and sent things off to the foundry. The firmware for the ADAT was all written in 8031 assembly language on an HP 64000 Logic Development System, which was kind of a standard at the time. No PCs, no high-level C language or anything like that. There also wasn’t a lot of memory available and latency was a big deal, so everything had to be as efficient as possible.

Did you have any idea at the time how revolutionary the ADAT would be?

There was always a vision of what it would mean for the industry, so, yeah, we knew we were working on something big—but you really don’t know until it actually happens. After doing so much hard work, once it debuted we were finally able to actually step back and realize, “Wow, this is really cool.”

Fast Forward Designs eventually transitioned into Line 6. How did that happen?

Marcus and Michel, who were obviously the brains behind all this, began thinking about making a digital modeling guitar amplifier, and luckily there was no conflict of interest with any of the projects we were working on. Nonetheless, the research was a closely guarded secret that had to be kept from everyone who wasn’t directly involved, so we had a code phrase to alert everyone when, say, someone from Alesis was in the building. There were five rotating phone lines, and Eric Von Ploennies was the first engineer to work on the guitar amp, so the receptionist would get on the intercom and say, “Call for Eric on line six,” and that would alert everyone because there was no line six. Then, when it came time to select a brand name, various options were considered and Line 6 was chosen for several reasons, including that there are six strings on a guitar, but also because it was generic enough not to force us into making any specific type of product.

Hatzinger at Yamaha Guitar Group headquarters in 2022, flanked by an ADAT, an early POD, POD Go, and HX Stomp XL.

So Line 6 was originally just the brand name and Fast Forward Designs remained the company name for a while?

Yes, Fast Forward Designs was still the name of the company that was doing consulting for other companies, but we needed a brand name to release the AxSys 212 guitar amp under. At that time most of us were still working on the various versions of the ADAT—the XT-20, LX-20, and M-20—as well as doing work for other companies. Once we began making the AxSys 212 and other products, the company grew pretty fast and needed people beyond just the engineers. So then we started getting sales people and marketing people and finance and purchasing and production and customer service people. We also did all the manufacturing ourselves here in the U.S. at first, so we added a production facility, and at about that time we decided to gradually phase out the consulting work and focus exclusively on our own products. That’s about the time that the name of the company officially changed to Line 6.

Your role also changed at about that time, right?

Yes, I transitioned from writing code to project management, which suited me really well and fit with my personal goal of having a family. Engineering required being in the building at specific times in order to work on the equipment and with other team members. With project management I was able to alter my schedule. I’d start at around 6:00am, and then be able to leave in the afternoon to pick up my kids from school, be at home with them, take them to their various extracurricular activities, and things like that. The company really worked with me to find a good way to meet both its goals and my personal goals—and I’m still here all these years later.

What are the most rewarding aspects of working for Line 6 and now Yamaha Guitar Group?

Mostly, I appreciate having the opportunity to work with so many really smart, creative, and artistic people. It’s very rewarding to see how our products are used to create music and support self-expression. My music background played a more prominent role early on when I was involved in discussions about user interfaces and product implementation, but it’s still what keeps me connected. Traveling to China and Malaysia to visit the factories and meet our teams there was also very enlightening. And then becoming part of Yamaha and traveling to Japan for the very first time was amazing and filled with many memorable experiences.

What advice would you give to young women who are either considering a career in engineering or have already recently embarked on one?

I’d say don’t let anyone hold you back from pursuing a career in engineering or any other field just because you’re a female. Understand your strengths as well as your weaknesses and work hard to do your best. You’ll gain respect and prove that you deserve to be there as much as anyone else. That’s advice I would give to anybody, male or female, but certainly female. Sometimes we have to work a little bit harder to prove that we belong, that we can do the job just as well. Don’t give up, believe in yourself!

ADAT, BRC, and Team ADAT photos courtesy of George Petersen Archives

Carol Hatzinger 2022 photo: Steve Geer

Barry Cleveland is a Los Angeles-based guitarist, recordist, composer, music journalist, and editor-in-chief of Model Citizens and The Lodge, as well as the author of Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques and a contributing author to Stompbox: 100 Pedals of the World’s Greatest Guitarists. Barry also served as an editor at Guitar Player magazine for 12 years and is currently the Marketing Communications Manager at Yamaha Guitar Group. barrycleveland.com

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

What an absolutely fantastic story! Thanks for sharing!

I remember when ADAT’s landed in our local studios. Complete game changer.

Thanks for all you have done over the years!

I am 70 yrs old..I have had a ,long, long Bassist Career , traveled the world….only because of her hard work and those compadre’s she worked with…., was this possible , at the time , you could not record, the cost was 350+ an hour…(now that i pay for electric bill, i get it)….but you made it possible to capture live performance (musicianship) at a cost with some sacrifice we all could afford….truly a Hero for all real musicians to give thanks for…..a great example at a time girls need examples more then ever….glad you are being celebrated!….

Fascinating–talk about “hidden figures.” There should be a statuette of Ms. Hatzinger in every recording facility everywhere!

What an amazing story, thank you! Ms. Hatzinger unknowingly you have touched my life for decades. As a former machine code programmer, I appreciate what you did to make ADAT happen and wow! This emphasizes why I prefer to work with young people: We/They don’t know limitations or what “is enough” so the work output is HUGE and that helps everyone. It’s a privilege and empowerment to have unknowingly followed your accomplishments since the 90’s. I’m anxious to follow in your next steps!

That early photo hits home. HUGE terminals, open circuit boards, a VHS cassette, and I can almost smell that soldering iron.

This was an uplifting and inspiring story.

Thank You … for your game-changing work.

As a professional musician from that era,

I too. remember analog tape sessions and

and the ADAT revolution. Truly Remarkable.

Wow, great article! Ahh the memories…I gladly blew a portion of my student loans to buy an ADAT in 1993 (I think it was about $3800) and combined with a StudioMaster 16 and a Roland S760, we were finally in the game. I still remember the first test recording like it was yesterday- I was alone, but the clarity and high quality of the playback sounded like someone else was live on a mic, so it literally startled me! It got our band on the local radio, and also gigs doing commercials. Thank you Carol for all your hard work, I had no idea that the ADAT and Line 6 were connected by the thread of her genius!