Peter Hook—Revisiting Joy Division and Factory Records

by Barry Cleveland

Few labels are as storied as Manchester-based Factory Records. Founded in 1978 by media host Tony Wilson, actor Alan Erasmus, and band manager Rob Gretton, Factory Records was the early home of an eclectic assortment of bands that included The Durutti Column, Cabaret Voltaire, and Joy Division. Although these bands had little in common stylistically, the label’s early releases were produced by recording iconoclast Martin Hannett and sported distinctive artwork by graphic designer Peter Saville, resulting in a de facto label sound and image. The label debuted with the release of A Factory Sample in late December 1978—a double EP that included two Joy Division tracks—and ended in 1992 (though other Factory-related businesses appeared and disappeared for at least another decade). The 2002 film 24 Hour Party People provides a glimpse of at least part of the story.

Joy Division are arguably the most historically significant band associated with Factory Records. Vocalist/lyricist/guitarist Ian Curtis, guitarist/keyboardist Bernard Sumner, drummer Stephen Morris, and bassist/backing vocalist Peter Hook originally formed to play unadorned punk, as attested to by their earliest recordings—but in the hands of Martin Hannett they crafted two albums that largely defined the post-punk sound. With their dark, moody ambience and unprecedented use of digital effects, Unknown Pleasures and Closer remain highly influential nearly half-a-century later. Joy Division came to an early end with the tragic death of Ian Curtis on May 18, 1980.

Here, on the occasion of Record Store Day, we speak with Joy Division and New Order bassist Peter Hook about Joy Division, the early days of Factory Records, Martin Hannett, his unique bass playing style and sound, and how he uses his Line 6 HX Effects processor when performing live with his current group Peter Hook and the Light.

What distinguished Joy Division’s relationship with Factory Records?

Well, the truth is that we were all really young and naive and none of us actually knew what we were doing so we were in very good company. One of the things I liked about Tony in particular was that he never did anything for money. It was all for his art or his interpretation of art. For example, it was his idea to split the money 50/50, which was unheard of, and he was very hands off when it came to our music, leaving us to our own devices, which is a fairly anarchic way to run a record label. We also all believed that the music should speak for itself and were essentially anti-promotion. We didn’t put our names on the record covers, we didn’t put the singles on the LPs—our attitude to selling records was terrible. Nonetheless, Factory had at least ten fantastic years with the success of Joy Division and New Order, apart from the hiccup in the middle.

Was it also a matter of being in a certain place during a certain period of time?

That punk and post-punk period was a fantastic time for music in England and the world. There was a great acceptance and an opening of being able and willing to listen and take a chance on anything that was unparalleled.

Because the early Factory releases were recorded by Martin Hannett and featured artwork by Peter Saville there’s a sense of continuity and label identity—but in reality, the bands actually all sounded very different from one another. How did bands get signed to Factory?

Honestly, it was mostly a matter of who came up to Tony and what they said to him. It was that free. Famously, Ian Curtis was absolutely horrific to Tony the first time we met, but Tony remembered him. Tony seemed to thrive on things that weren’t normal and that were difficult and ornery. I mean, he famously turned down the Smiths because he thought they were boring and he turned down the Stone Roses because he thought they were too Manchester.

Unless someone saw Joy Division perform live during the short time that you were together, when they think of the band’s sound they mostly think of the recordings—but didn’t the live band sound quite different?

Well, even in that brief time our sound changed quite a bit. When we first started out all we wanted to do was rip peoples’ heads off like the Clash or the Sex Pistols, and Martin didn’t actually change our sound that much when we recorded “Glass” and “Digital” for A Factory Sample. That was very much how Joy Division played and sang and sounded. But when we recorded our first album, Unknown Pleasures, Martin realized that there was something else that he could do with the group, and as long as he didn’t listen to us and we didn’t get in the way he would be able to do it, which is exactly what happened. Martin made the music deep and meaningful, with the ability to influence generation after generation, and Bernie and I wouldn’t have done that. We were actually very unhappy with the album at the time, though Ian and Stephen liked it.

Though by the time you were recording Closer didn’t you already know what Martin was up to in terms of the processing and production techniques?

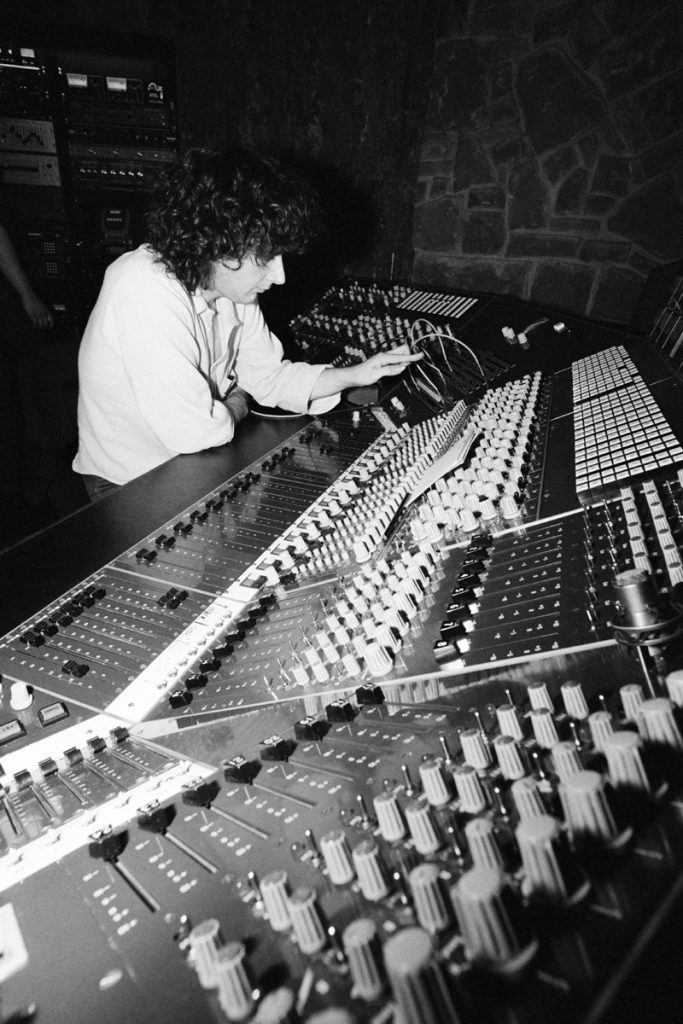

Yes, and Bernie and I fought with him constantly. We’d sit on either side of him at the mixing desk and take turns demanding things and most of the time he would just freeze up and say something like, “Just let me get on with it, you idiots.” His attitude was that musicians should neither be seen nor heard, which was quite odd given that he himself was a musician. Though, again, he was absolutely right not to listen to us.

Would it be fair to call him the fifth member of Joy Division, as some have done?

No. He didn’t write any of the songs or even particularly change any of the music. He just had his very idiosyncratic recording techniques, which changed the sound of the music.

What are a few examples of those techniques?

One of his big things was clarity. Everything had to be recorded as cleanly, clearly, and separately as possible, which involved putting microphones really close to amps and instruments and recording DI signals in addition to using mics. That’s all absolutely correct, but it meant that if we had tried to remix it ourselves, we would have listened to the unprocessed tracks and thought, “Oh my God, this sounds terrible.” He had the vision and the experience to be able to imagine how it was going to sound once he had added all of his effects and mixing tricks and we didn’t.

Those effects included the AMS DMX 15-80S Digital Stereo Delay, the Marshall 5402 Time Modulator, a Melos Echo Chamber tape delay, and EMT plate reverbs. Do you recall any specifics as to how he used them?

Well, although he worked with AMS on the development of their delays and reverbs, what he actually used the most were the EMT plates. Strawberry Studios had two huge EMT plates that sounded absolutely wonderful and he used them to build up his own Phil Spector-style wall of sound. But his biggest influence as a producer was Tamla Motown. They had an acoustic echo chamber in the attic above the studio at Hitsville USA that they used to get all those great echo and reverb sounds and that was what inspired Martin’s trademark sound more than anything else.

Your bass sound on Closer is bigger, fuller, and clearer sounding than on Unknown Pleasures. It was a different studio and I believe you used a different amp, but didn’t you also play a different bass?

Yes, I played a Shergold Marathon 6-string bass on the majority of the songs, which was the main difference. But I also didn’t use my own effects on Unknown Pleasures, whereas on Closer I used an Electro-Harmonix Clone Theory analog chorus and a Yamaha delay unit set to 80 milliseconds to fatten things up. Of course, Martin also added his own effects sometimes, or used them instead of mine. The 6-string bass sounded really different than the 4-string and a lot of people thought some of the bass lines were guitar lines.

Is the Marathon tuned like a guitar with E as the lowest string?

Yes, it’s tuned E, A, D, G, B, E, low to high.

Do you ever play with your fingers instead of a pick?

I’ve always played with a pick and I’ve always hit the strings as hard as I could [laughs].

Did you always play through an amp when recording with Joy Division or did you ever plug directly into the board?

Martin recorded my amp, but he also used to record a DI signal, though I really had no idea why at the time.

What is an example of another recording technique used when recording your bass?

Because my parts often included an open string used as a sort of rhythmic drone, we would record the open-string part on one track, and the other parts on another. For example, on “She’s Lost Control” we recorded the rhythmic open D part on one track and the melodic G-string part on another track, and then combined them. That way we could put more bottom end EQ on the open string without muddying up the higher, melodic part. And I continued to use that technique with New Order.

Much is made of your playing high on the neck, but your use of open-string pedal points and chordal figures combined with melodies is mentioned less frequently. Is there anything else that you feel gets overlooked in your playing?

My playing is actually a lot simpler than most people think. For example, people argue with me about how the bass part on “Love Will Tear Us Apart” is played [laughs]. I always go for the simple thing, but maybe in some cases because of the recording techniques the parts sound more complex than they really are? Also, the vast majority of Joy Division’s songs were written from jams. We weren’t actually playing “songs,” like in a studio format, we were playing in a group format, jamming together—and to me that was the strength of Joy Division.

Is that why most Joy Division songs don’t follow typical songwriting structures and more or less stick to a single tonal base with only minimal changes?

Yes, we’d start with jams and then build over them. If you look at a song like “Transmission,” the bass hardly changes throughout it and you might say, “Oh, that’s dead simple, that.” But nobody else has written a song that sounds like it. “At a Later Date,” “Novelty,” they all have a bass riff that goes all the way through and hardly changes. That leaves room for the guitar to put different parts on it. If we would have made the bass more complicated, we wouldn’t have achieved what we were trying to do. It was a formula: Ian would sing and I would do the backing vocals with him, Bernie would play guitar and sometimes keyboard, and the bass and drums would carry the song.

What do you make of the resurgence of vinyl in the last 10 years or so?

It doesn’t surprise me at all. As sad and old-fashioned as it may sound, nothing gives me more joy than getting a record out of its sleeve, putting it on the turntable, and hearing those first few little scratches at the start before the music comes in. It’s a fantastic way to listen to music and as much as I have embraced digital, it’s still wonderful to have something so tangible. It’s the perfect medium to listen to music on. The size of the sleeve, and the fact that you can hold it in your hands.

The concept of albums is rapidly being replaced by individual tracks and personal playlists. Do you have any thoughts about that?

Many musicians, especially older musicians, are so used to working in that format that it’s the only way they can do it. That said, in the early days of Joy Division we weren’t writing tracks for an LP, we were writing songs we could play live, and we needed about ten or so to play our first gigs.

Sure, but by the time you recorded Closer you were thinking in terms of a collection of songs that comprised an album, right?

Yes, very much so, though the problem with Closer is that we had only completed four or five songs in the studio before Ian died, and the others were completed posthumously. Joy Division had never actually played most of the songs live.

How long have you been using Line 6 gear?

A long time, starting with both the walnut-shaped red guitar and grey bass PODs, which we used in the studio all the time. And later I got a DL4 delay pedal, and eventually had about seven of them! I still have some of those units.

What Line 6 gear are you using currently?

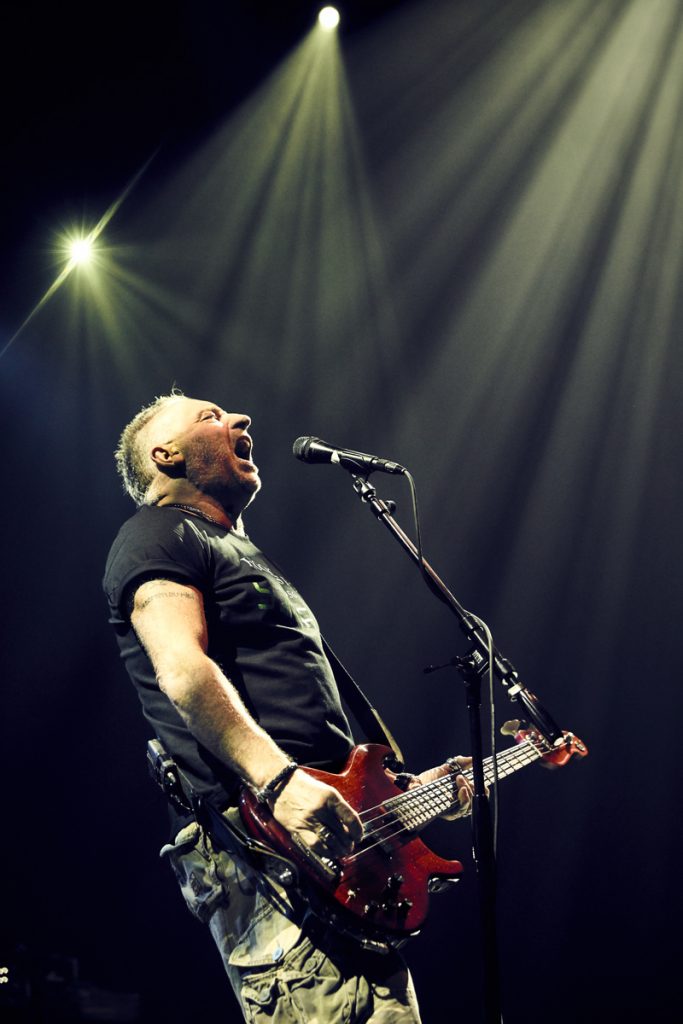

I use an HX Effects pedal in conjunction with the Clone Theory chorus when performing live. I also have several Helix Floor units, which my son is valiantly teaching me how to use. To be honest, I’m a bit of a traditionalist and I like my echo to be an echo and my chorus to be a chorus and my fuzz box to be a fuzz box—but I have to be realistic when touring because I can’t take all that stuff with me. HX Effects does a wonderful job of putting everything together and it sounds great.

Which effects do you use the most?

I use the 70s Chorus as a backup to the Clone Theory, the Wringer Fuzz for slight distortion, the Kinky Boost for some solos, short and long delays, and the 10 Band Graphic EQ. The EQ is just used to boost the volume of the Shergold 6-string bass, which has passive pickups, to the match the level of my Yamaha BB bass, which has active pickups. I find that with a little bit of effort and work the HX Effects can do everything that I want and need—and it’s also very reliable. Mine comes with me all around the world and it’s never let me down once. So that’s something that can’t be said for the old stuff, sadly.

Any thoughts on Record Store Day?

Supporting Record Store Day is an absolute pleasure. I have the same reverence for vinyl that I did when I was a kid walking down the street with, say, my Black Sabbath album so everybody could see that I had it. It was so important to me then and I’m still very much tied to that!

Joy Division, Factory, and Martin Hannett photos: Kevin Cummins, Getty Images

Peter Hook live photo: Travis Shinn

More information on Martin Hannett may be found in Chris Hewitt’s book Martin Hannett – Pleasures of the Unknown.

Barry Cleveland is a Los Angeles-based guitarist, recordist, composer, music journalist, and editor-in-chief of Model Citizens and The Lodge, as well as the author of Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques and a contributing author to Stompbox: 100 Pedals of the World’s Greatest Guitarists. Cleveland also served as an editor at Guitar Player magazine for 12 years and is currently the Marketing Communications Manager at Yamaha Guitar Group. barrycleveland.com

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Hooky is my kind of old school kind of gear guy, but I also appreciate that Jack is teaching him how to use the HX Effects! #LineSixRules

Peter Hook is my favorite basest. His tone is legionary. I twice saw him perform in DC. The last time I saw him his son played bass whilst he sang. You could tell that Hooky was very proud of his son. I watched this performance with my son. It was special day.