Jakko Jakszyk – Helix In the Court of the Crimson King

by Barry Cleveland

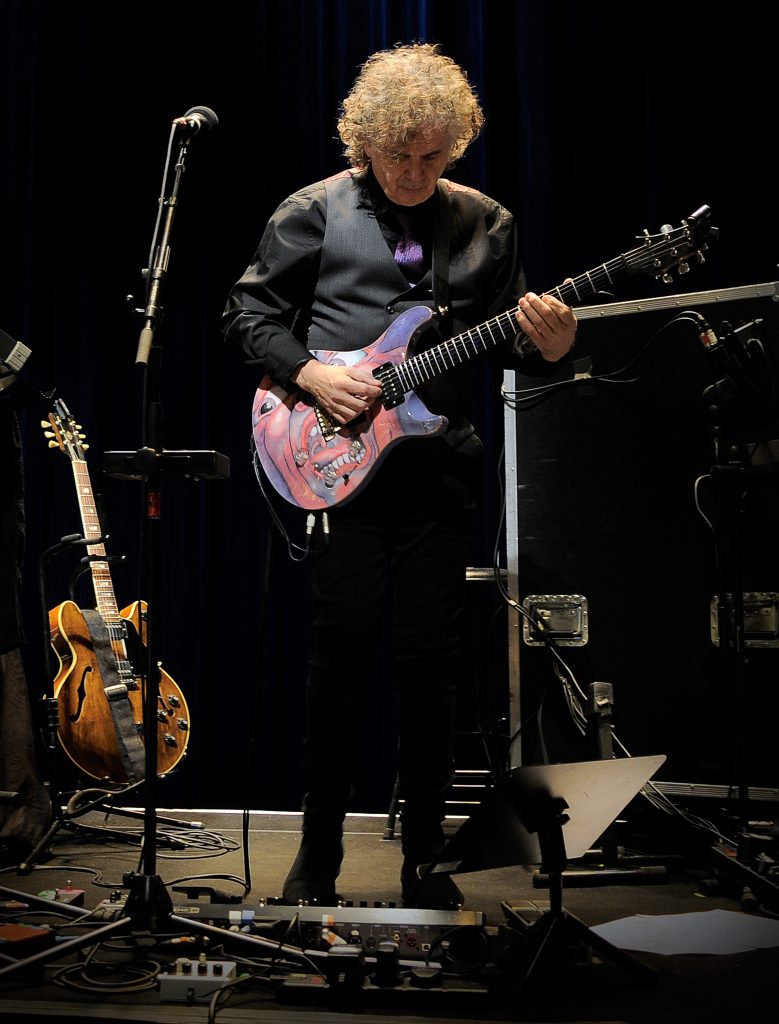

Guitarist and vocalist Jakko Jakszyk has been a member of King Crimson since guitarist Robert Fripp reformed the group in 2013. This latest incarnation of King Crimson mostly performs reimagined versions of material spanning the band’s entire history back to 1968. Jakszyk is tasked not only with playing many of Fripp’s frequently challenging guitar parts, but also with singing songs originally sung by idiosyncratic vocalists such as Greg Lake, Boz Burrell, Gordon Haskell, John Wetton, and Adrian Belew—an equally daunting task.

Jakszyk had worked with Fripp and several other current members of King Crimson previously on the 2011 Jakszyk, Fripp, and Collins album, A Scarcity of Miracles. In addition to the two guitarists, the recording featured Mel Collins (saxophone/flute), with contributions from Tony Levin (bass/Chapman Stick) and Gavin Harrison (drums). Fripp and Collins also played on Jakszyk’s 2006 album, Bruised Romantic Glee Club.

Additionally, Jakszyk succeeded Allan Holdsworth in Level 42 and was a member of Canterbury Scene rock band Rapid Eye Movement, as well as working with Steve Hackett, Steven Wilson, and members of Japan, Henry Cow, and Golden Palominos, among many others. He was also a member of The Kinks for two weeks.

The guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter released his superb Secrets & Lies in 2020, an eclectic amalgam that encompasses Crimson-like art rock, Middle-Eastern-tinged experimental pop, fuzz guitar soloing with orchestra accompaniment, and straight-ahead rock ballads. The album features a diverse lineup, including Fripp, Levin, Collins, and Van der Graaf Generator vocalist and guitarist Peter Hammill. A unique animated video for the hauntingly beautiful “The Trouble with Angels” was produced by Iranian filmmaker Sam Chigini.

In addition to his musical endeavors, Jakszyk has distinguished himself as a remixing engineer, creating stereo and 5.1 surround sound mixes of classic albums by Jethro Tull (Minstrel In the Gallery, Heavy Horses), Emerson, Lake & Palmer (Brain Salad Surgery, Trilogy), King Crimson (Thrak), Chris Squire (Fish Out of Water), and The Moody Blues (In Search of the Lost Chord).

Jakszyk relies on his Helix Floor when crafting legacy and contemporary King Crimson tones. He has kindly elected to share three of his presets with Model Citizens readers.

There are some wonderful guitar tones on Secrets & Lies. Were they created primarily with Helix?

Yes they were. I use Helix for practically everything I do these days.

Three of the tracks on that album were originally proposed for King Crimson. How did they wind up on your solo album?

I wrote “Uncertain Times” in response to the extreme political polarization taking place in England and around the world. The title came from Robert Fripp and Gavin Harrison came up with the rhythmic things in the end section, but the rest I wrote on my own. It was one of a number of songs I presented to Robert to be considered for King Crimson that didn’t make the cut. We used to have a joke where I would play something and he would either respond to it or say, “I love this track. It’s fantastic. It’d make an ideal track for your next solo record,” which was code for, “We’re not playing this.”

“Separation,” the epic tune at the end of the record, is something that I pieced together. Robert would come round to my studio on occasion and play me some sections of new things he was working on, and I would record the parts to a click so they could be worked with later. On that particular piece I had Gavin play drums and Tony play bass and I built it up into a complete song. Robert liked it, but, again, it never became a full-on Crimson track.

The third one, “Under Lock and Key,” includes what sounds like ’70s-era “Frippertronics” tape looping.

That’s what it is. I have access to all of the archival stuff, and that recording had a bit of a vibe and inspired the tune. Gavin and Tony play on that one as well.

The inimitable Peter Hammill sings and plays guitar on “Fools Mandate.” How did you come to work with him.

Van der Graff Generator’s Pawn Hearts is one of my favorite records ever, and I listened to it relentlessly when I was a school boy, along with Peter’s early solo albums. Dave Jackson, the saxophone player in Van der Graaf, played on my first record and I met Peter through him. For several years I kept running into Pete at an awards ceremony we attended and each time he would encourage me to make a solo record, so I said, “I promise I’ll make one if you agree to appear on it.” He asked if I had any unfinished tracks, and I sent him one of the more exotic ones. He sent back some vocals with lyrics and even put some guitar on it. I ended up writing a song about the British involvement in the Middle East around the end of the First World War, which I’m told is unlikely to get me a Top 10 hit [laughs].

You said he played guitar. Who played the Middle Eastern-inflicted bits and the cool solo?

That’s me. Pete played a load of noisy guitar at the very end, but the whole kind of Arabic scale thing is me.

As a member of this incarnation of King Crimson, which primarily plays material originally performed by other lineups, how do you strike the right balance between being faithful to the original music and presenting your own musical identity?

When playing the older material, having two guitarists in the band enables us to recreate some of the overdubbed parts on the recordings, and in those cases I naturally feel that I need to be true to the original parts. For example, “Sailor’s Tale” has got a three-part harmony section with two guitars and saxophone, so I play the overdubbed part using the tone on the record. In fact, when we first rehearsed that piece Robert said, “That sound was very good,” because it sounded like him. Then he asked, “Did you program that?” I said, “No, it’s a preset I found called ‘Early Fripp,'” which he thought was very funny. As for my own musical identity, I do have opportunities to deviate from the original parts in some cases, and also on some of the newer material.

You face a similar situation regarding your vocals, where you are singing songs originally performed by five different vocalists, none of whom sound alike. Some Crimson fans say that you don’t sound enough like the originals, whereas others say you sound too much like them.

Because those are the records I listened to growing up, and I was influenced by those vocalists, my singing is very much informed by them as sources of inspiration. But I’m not doing an impression of them, I’m singing as myself. Also, to be fair, the majority of the feedback from Crimson fans is very, very positive. There is a small element of what I describe as the militant wing of the Adrian Belew fan club that … but listen, what are you going to do? If you get offered a job like this, you take it, and you do it to the best of your ability in as honest and true a way as possible.

Describe how you use Helix with King Crimson.

To begin with, one of the reasons Tony and I use modelers is that we can’t have loud amplifiers onstage. Rather than having the lead singer down the front, and the band surrounding him like they’re supporting him, which of course is his natural and rightful position, Robert switched it round and put the three drummers out front, with us on risers behind them. That means that the sound of amplifiers would go directly into the drum overheads, which would be problematic. I used to use a different modeler, but when I was given the opportunity to try Helix during a tour, even though the Crimson gig is technically sufficiently difficult to not want to switch to an entirely new system, that’s what I wound up doing.

What was it about Helix that made the switch worthwhile?

My guitar has a piezo pickup in the bridge and two outputs, one for it and one for the magnetic pickups. Because there is a lot of acoustic guitar on the earlier Crimson material, I would blend the two sounds to cover two sounds simultaneously. Before I got the Helix, I used to route the piezo signal directly to the P.A., and use a switch or a volume pedal to turn it on and off, but I was forever forgetting to either bring the piezo in or pull it out, which was a real pain. Because Helix lets you have two independent inputs and signal chains, I was able to process the two signals independently and then save the whole thing as a single preset, which was fantastic. Later, I began experimenting with using the piezo sound as a tonal element within the preset rather than just as a replacement for an acoustic guitar. For example, if you bring it in under a clean electric sound it adds a really nice presence.

Another thing that is really useful is that you can turn the effects off and on so easily within a preset. For example, on “Larks’ Tongues In Aspic Part 1” I play this big slide-y fuzz part that on the record suddenly opens up and goes into this reverb wash on the final note, and recreating that within Helix is very easy.

Anything else?

My rig fits into a little flight case, compared to Robert’s huge racks of stuff and so many pedals on the floor that it makes my head spin just to look at them. And I can’t count all of the times that guitar players I respect and admire have come up to me and asked, “Wow, how on earth did you get all those great sounds?” When I point to Helix they can’t believe that’s basically my entire rig.

Do you use different amp, cab, and effects models for all the various King Crimson tunes, or do you have some go-to sounds that you use frequently?

For the classic tones from the ’70s I try to more-or-less replicate Robert’s rig from that period. For example, he used Hiwatt amps, so I use the WhoWatt 100 amp in Helix for some of those songs. But for some of the other songs, I’ve built up whole other sound scenarios, just because of how they feel and sound in the moment. An example of that would be using the Vermin Dist to get some of the fuzz sounds, though I don’t think Robert ever used a Rat fuzz pedal.

So much of the sound has to do with the player as much as the gear.

Yeah. I remember seeing Allan Holdsworth sit in with someone and when he borrowed a Telecaster I thought, “Oh, that’s going to sound horrible.” But it sounded like Allan Holdsworth, because he was Allan Holdsworth. Speaking of which, Allan was really sweet to me when I was a lad. Robert had said in an interview that Allan was the only guitarist in England worth listening to, so I went to see him with Soft Machine and his playing was like nothing I’d ever heard before. Later, I learned that he had joined Gong, which were signed to Virgin Records. I phoned Virgin, put on my best Yorkshire accent, and pretended to be a friend of his. I said, “I’m trying to track down Allan. You haven’t got his number, have you?” They gave me his number, so I phoned him up and said, “I’m an enormous fan. Do you give lessons?” He replied, “No, I don’t know what I’m doing, so I’d be useless giving lessons.” I was about to hang up when he asked if I’d like to come round to his place. As I recall, I went there every week for a while and he taught me about compression and other technical things.

Much of the Crimson material utilizes polyrhythms, cross-rhythms, and other challenging things to play. What’s an example of a particularly difficult one?

When Robert and I first got together after the band was formed, he said that he thought we should do “Larks’ Tongues In Aspic Part 1,” and as a fanboy I thought, “Oh, brilliant.” Then he said, “The trouble is that it is very difficult to play in my New Standard Tuning, so you could play that, seeing as you’re in standard tuning.” And I remember thinking, “I can’t play that. Are you insane?”

But you do play it nonetheless.

Yeah, I play in alternate bars of 10 and 11 or whatever it is—I don’t even count it—whilst the rest of the band are playing in seven, and I know that I have to begin on beat four of the fourth bar of seven. When we first started rehearsing it, I had no idea if I’d got it right until we reached the end and we all landed on the same beat. I just concentrate on the pulse, and the rest is all subdivision. Funnily enough, if you ever asked Allan Holdsworth what time signature he was playing in, he would say that he was playing in one and that everything was in one.

To complicate matters even further, you sometimes have to sing at the same time that you are playing those difficult guitar parts.

That’s the other thing. Those sorts of challenges force you into uncomfortable and difficult places and you have to find a way to survive and come out of them.

We can’t end the interview without my asking you how you found yourself playing in The Kinks.

One Sunday evening in about ’94, I got a call from a guy claiming to be a promotions bloke from The Kinks’ organization. He said Ray Davies wanted to know if I was available for a couple of weeks to play a radio broadcast on the BBC and some television stuff, because Dave Davies was ill. When I asked if he was sure that Ray had asked for me he said yes. Less than an hour later I met the guy at a service station and he gave me a cassette containing a bunch of music to learn.

The next day I drove up to Konk Studios for rehearsals and the rhythm section was Jim Rodford and Bob Henrit, from the band Argent. Then in walks Ray and I’m thinking, “This is just too surreal. I used to watch him on Top of the Pops.” So, after two days of rehearsals we go to the BCC to play on Radio 1. At the end of the first number the DJ goes to a live conversation with Ray and says, “I understand Dave is not with you today,” to which Ray replies, “No, he’s not well.” Then the DJ ask him who is playing guitar and Ray says, “We’ve got…” And in the end he said, “My granddad.” And I thought, “Bloody hell, he doesn’t even know who I am.”

Then we go into “All Day and All of the Night,” which has a simple bluesy pentatonic solo, and I’m so annoyed I’m flying all over the place rather tastelessly. And when the song ends, the DJ says, “Great guitar playing there by Jakko.” And Ray says, “That’s right. Yeah, Jakko. Well done.”

I found out later that Dave wasn’t sick at all. He was living in Los Angeles, and he and Ray were having a fight at the time, so Ray thought, “What can I do to piss him off? I know, I won’t tell him about these gigs and we’ll get somebody else in.” There just happened to be a copy of Guitarist magazine that had me on the cover sitting on the studio coffee table, so Ray said, “Let’s get this bloke. He’s obviously a good player. And I know that Dave gets this magazine sent to him in LA, so that will piss him off even more.” And that’s how I ended up in The Kinks.

__________________

Download Three Helix Presets

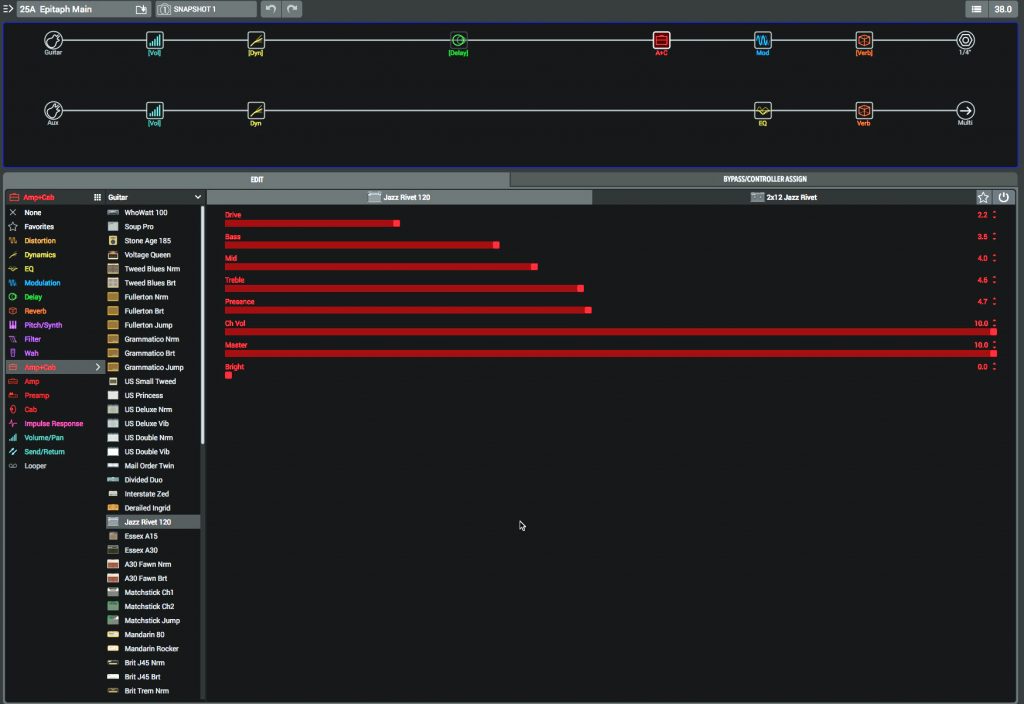

Epitaph

This is the basic sound I use for “Epitaph.” It combines the piezo and magnetic pickups, and so will be of most interest to those with a two-output guitar. The signal chain for the magnetic pickup is: Volume>LA Studio Comp>Adriatic Delay>Jazz Rivet 120>Bubble Vibrato>Plate. The signal path for the piezo pickup is: Volume>LA Studio Comp>Simple EQ>Plate.

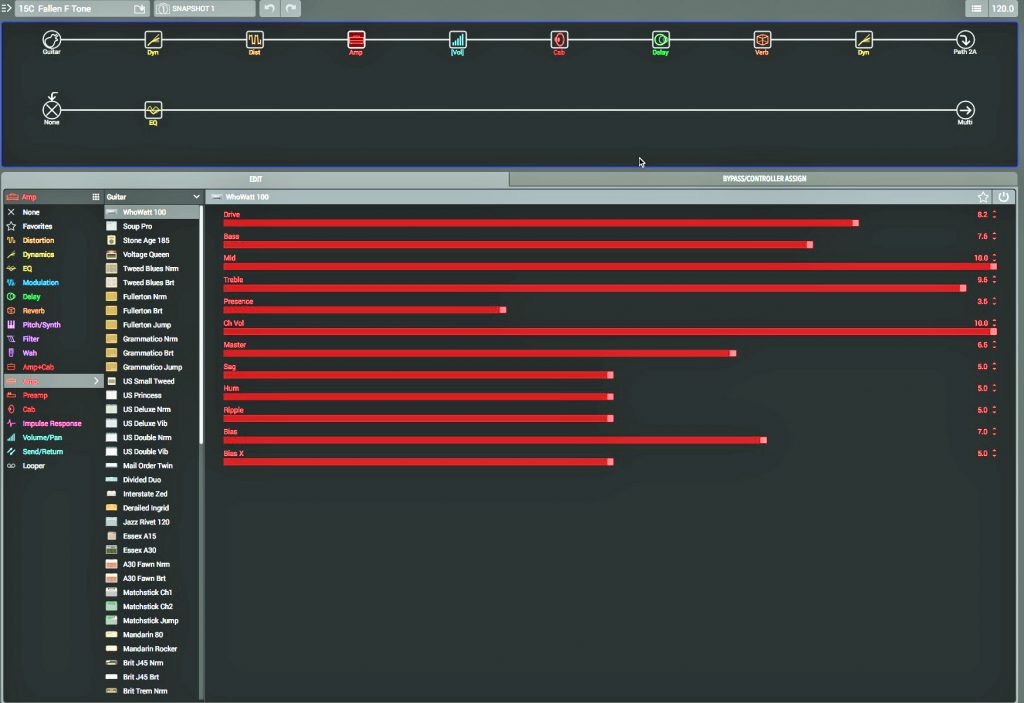

Fallen F Tone

I use this preset to emulate some of Robert’s sounds on “Fallen Angel,” specifically certain overdubbed parts or when I play a line because he’s playing something else. The signal chain is: Noise Gate>Vermin Dist>WhoWatt 100>Volume>4×12 1960 T75>Simple Delay>Plate>LA Studio Comp>Simple EQ.

Radical Oct

This is named after “Radical Action (To Unseat the Hold of Monkey Mind),” a new song, though I also use it for the heavy riffing on “Starless” and “Indiscipline.” The signal chain is: Noise Gate>Simple Pitch>Line 6 Epic> 2×12 Blue Bell>Simple EQ>Volume>Hall>6 Switch Looper.

More about Helix.

Main Photo: Spike Mafford

Barry Cleveland is a Los Angeles-based guitarist, recordist, composer, music journalist, and editor-in-chief of Model Citizens and The Lodge, as well as the author of Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques and a contributing author to Stompbox: 100 Pedals of the World’s Greatest Guitarists. Barry also served as an editor at Guitar Player magazine for 12 years and is currently the Marketing Communications Manager at Yamaha Guitar Group. barrycleveland.com

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

This is really a great article, I like the combination of the in depth interview, the audio/video fragments, and the shared preset! Keep on using this combination in the blogs!

“There is a small element of what I describe as the militant wing of the Adrian Belew fan club…”

Hey! I’m sitting right here!

Seriously though:

My wife and I saw the Elements tour. Drove from Homer, AK to Seattle to see it. Good Gravy! Crimson! One of the best concerts we’ve ever heard. Thank you, Jakko.

BTW, I also went to see Levin, Bruford, Belew, and that weird guy that sits down, back in the day. ALSO one of the best concerts I’ve ever heard. There you have that, I suppose.

Only one thing I missed – did Jakko used IRs or stock speakers?

spyr01d you can clearly see in the screenshots, he is using stock cabs