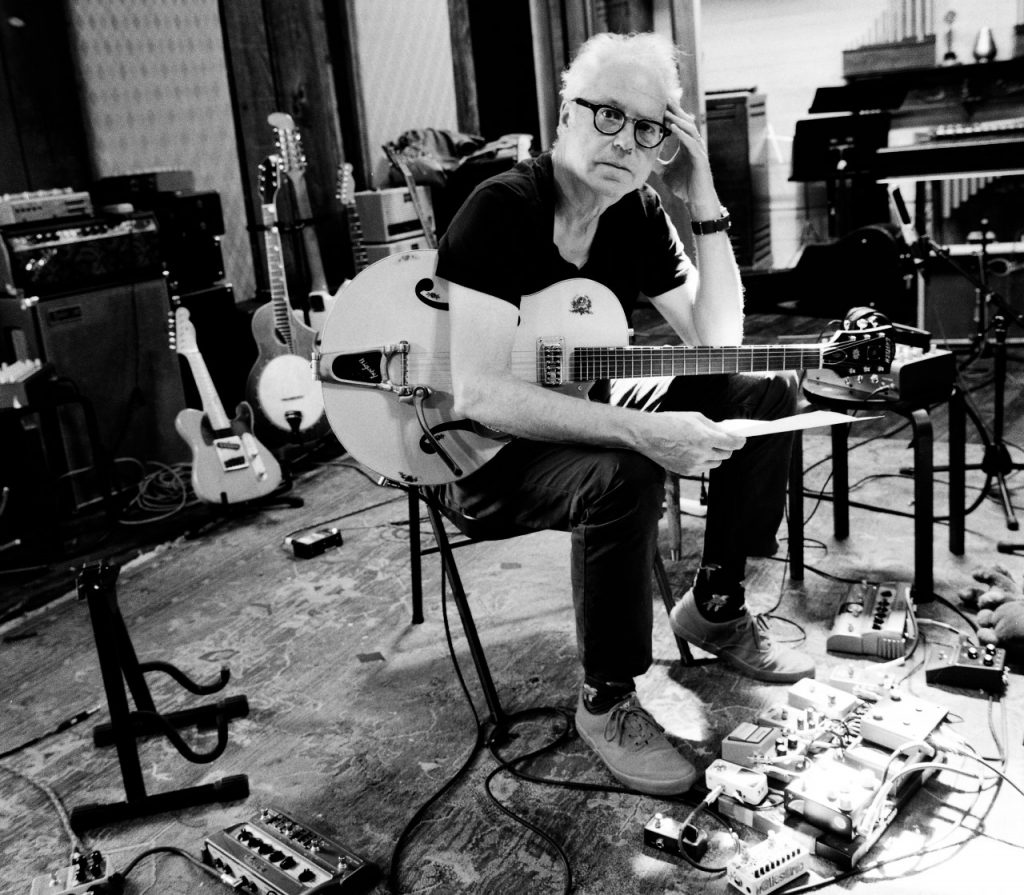

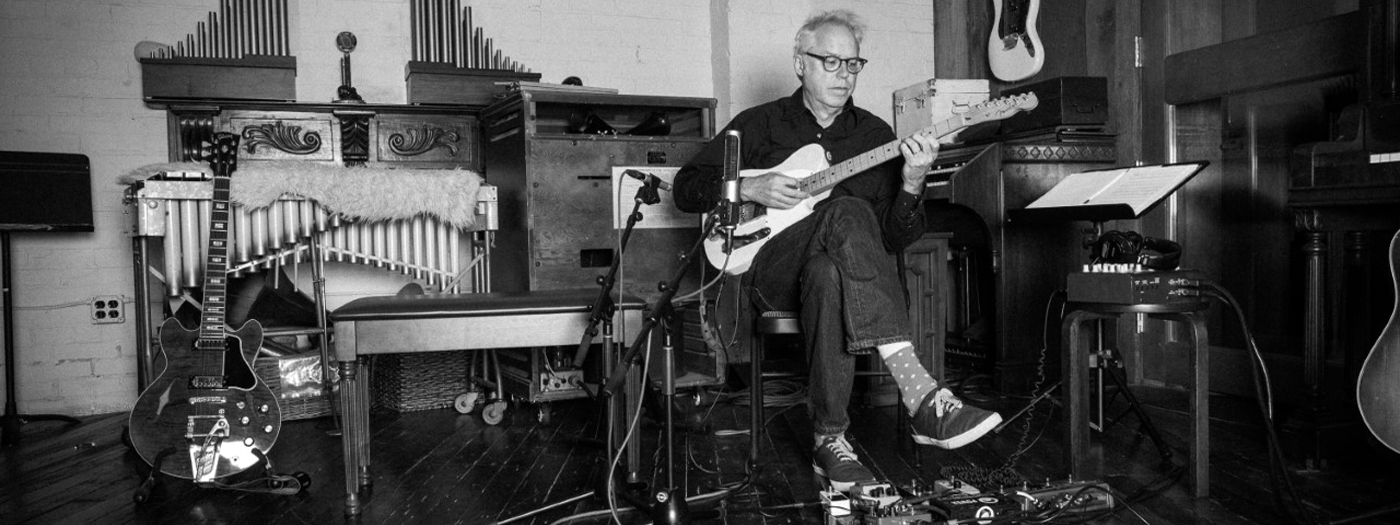

Bill Frisell Talks Looping & Loopers

by Barry Cleveland

Bill Frisell has been one of the world’s leading guitarists for more than four decades. His expansive discography includes numerous historic jazz milestones and his countless collaborations span nearly every imaginable genre.

Frisell is typically categorized as a “jazz” guitarist, though the label only begins to encompass his polyglot musical aesthetic. He speaks jazz, but his vocabulary is rich with expressions from blues, folk, rock, R&B, country, and other musical dialects, all somehow mysteriously blended into an organic whole.

Looping has always been an integral part of Frisell’s performances—from his masterful deployment of the notoriously finicky Electro-Harmonix 16-Second Digital Delay in the early years, to his current use of the Line 6 DL4 Delay Modeler, which he has relied on for looping and delay effects throughout the past 20 years.

Here, we trace the evolution of his looping and explore its importance in his music.

You are considered by many to be the master of the Electro-Harmonix 16-Second Digital Delay, which you used extensively early in your career. Did you have other delay devices before that?

I believe my first delay was a Univox tape echo, which recorded onto a cassette and was sort of a poor man’s Roland Space Echo. When that died I got a Boss DM-1 Delay Machine pedal that looked a little like a flying saucer, followed by a huge rack-mounted Yamaha analog delay. None of those did looping, though.

How did you first cross paths with the 16-Second Delay?

The late Robert Quine was a good friend of mine, and we used to have these crazy jam sessions. He bought one when they first came out, and when he showed it to me I just plugged in and instantly got sucked into it. That pedal took over my brain. I felt like I had been waiting for it my entire life.

What made it unique?

For one thing, there were two ways to change the speed of the loop playback once you had something recorded. One control changed the playback speed gradually, raising or lowering the pitch by small amounts. But there was also a control that changed the speed as if there were multiple tape heads spaced in different increments, and that would subdivide the speed into some sort of mathematical one-into-two, two-into-four, four-into-eight, and so on, which produced really dramatic effects.

You could also change the speed and pitch of a recorded loop, then put the delay back into record, overdub something else at regular pitch, then loop that and manipulate it by changing speeds or reversing it—and continue doing that indefinitely. You’d get all these layers of really different-sounding things that were all happening at the same time. What was really awesome about that was this sort of random surprise element, because there were so many ways that things could go off in directions that differed from what you were expecting.

What was it about that randomness that appealed to you?

For me, the music is always about trying to keep things in this area on the edge of what you can understand and what you can’t understand; what you know and what you don’t know. I want there to be some risk in it because to me that’s the point where it’s the most inspiring, when you’re off into this zone where you don’t know what’s going to happen. If you’re eight years old and you discover something for the first time, it’s like, “wow, this is the most amazing thing!” I’m trying to be in that space with the music all the time, and the randomness would transport me into that zone pretty quickly. I used it as a tool to organize sounds and melodies or whatever in more of a compositional way. It wasn’t so much about the guitar; it was like the pedal became this separate instrument.

At the same time, there were certain things that would go completely off the rails if you weren’t careful. For example, the regeneration wasn’t regulated in a way that would automatically keep it from going past the danger point, and it could potentially blow up your amplifier!

“For me, the music is always about trying to keep things in this area on the edge of what you can understand and what you can’t understand.“

Why did you stop using it?

It just quit working. I got another one, but it also stopped working, and by that time they were getting fairly expensive, if you could even find them. One of my greatest regrets in life is that once while I was visiting Boston a music store there had piles of them in the window on sale for $100. I could have cleaned up [laughs].

After that, I got a DigiTech 8-Second Delay pedal that I used for a really long time, but that was a huge step down, sacrificing a lot of what the 16-Second Delay could do. It didn’t even have a reverse function and the pitch control was so unpredictable that you never knew what note was going to come out when you moved it. That pedal was also very noisy. I continued using it even after getting the DL4, but eventually it stopped working and the DL4 became my main delay and looping pedal.

What is it about the DL4 that has worked so well for you for 20 years?

I’ve tried other things, but I keep coming back to the DL4 because at this point I’m so familiar with how it works that using it is super-intuitive and I never have to think about anything. In some ways the DL4 was a compromise compared to the 16-Second Digital Delay, but it also does a few things that the 16-Second didn’t do.

Describe a few of the core things that you do with the DL4.

You can create three presets and I’ve sort of settled into using those, even though I know there are a lot of different delay types to choose from.

One preset is just a basic delay thing using the Lo Res delay to kind of fatten things up. Another preset started with the Reverse delay, which is what I’m using whenever you hear me play backwards things. And the third preset is a ring-modulator-type effect you get if you start with the Reverse delay and set the delay time to as fast as it can go. A normal ring modulator lets you adjust the pitch, and this stays in one pitch area, but otherwise it is very similar.

Also, sometimes, I’ll select a preset and then mess with things like the delay time or the regeneration with my hand as I’m playing. Even when you’re looping you can still do basic delay stuff with the other knob and get these oddball sounds that maybe you add to the loop as it is playing. That’s actually a really cool thing to do. I only wish that there were a way to have the footswitches on the floor and everything else on a table, so that I could adjust the controls with my hands on the fly without having to bend down.

Something I do a lot with the looper, especially when I’m playing solo, is to find a simple rhythmic or melodic pattern that might work throughout a whole song, maybe with notes common to all the chords or just a single note or something, and play along with that.

Are you ever able to introduce randomness and the element of surprise into your playing using the DL4?

Yes. Sometimes I’ll play a couple of just random notes or sounds, not in any rhythm or anything, and capture them in a loop. Then, I might pitch those notes or sounds down an octave; or if the delay is already at half speed when I record the sounds, an octave up. I might also reverse the loop, or change the pitch and then reverse that sound. The idea is just to create some sort of textural sound that I can feed off of. Sometimes I’ll even turn the loop off and then bring it in later in the song, so it seems to mysteriously emerge from nowhere.

Even after all these years I’m still discovering new ways to use the DL4. Someone that I’ve played with who uses the DL4 a lot is Mary Halvorson. She uses it constantly, with an expression pedal, to do all sorts of amazing things that never even occurred to me. When I first saw her, what she was doing was so different that I didn’t even realize she was using that pedal.

Learn more about the DL4 Delay Modeler.

Main photo: Monica Jane Frisell

Barry Cleveland is a Los Angeles-based guitarist, recordist, composer, music journalist, author, and editor of Model Citizens and The Lodge, as well as the Marketing Communications Manager at Yamaha Guitar Group. barrycleveland.com

Related posts

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.