Barry Cleveland: How Joe Meek Turned the Recording World Upside Down

by Barry Cleveland

When I began researching my book Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques back in 2000, Joe Meek was commonly portrayed as an English eccentric who made quirky DIY records with excessive levels of compression, tape echo, reverb, and distortion in his home studio during the 1960s, one of which, “Telstar,” had become a worldwide #1 hit in 1962.

It was only after a year of acquiring and poring over copious quantities of written and recorded material, interviewing people who either worked directly with Meek or were knowledgeable about him, and listening to more than a thousand musical recordings from throughout his career, that a considerably more complete and accurate picture began to emerge:

Far from being a curious footnote in the annals of British recording history, Joe Meek was a giant whose approach to recording and recording technology was years and in some cases decades ahead of his time, and beginning in the mid 1950s his work had profoundly impacted and disrupted the entire British recording community—and by extension recording worldwide.

It can be challenging to put some of Meek’s contributions into perspective, however, because nowadays many of his “radical” innovations have been so thoroughly assimilated that we take them for granted, if we notice them at all, and it is difficult to comprehend how they could have provoked such a violent backlash from the majority of his contemporaries. We’ll examine a few of them, but first a little background:

Robert George “Joe” Meek was a precocious child. By the age of ten he had written and produced theatrical performances by and for the children in his village, and had built a crystal radio set, a microphone, and a tube amplifier. At age 14, he expanded his setup to work dances as a mobile DJ, and at 24 he built a disc cutter that he used to cut his first record—a library of sound-effects he had recorded on a homemade tape machine. Meek worked repairing radios, televisions, and other electrical devices before becoming a professional audio engineer.

Although frequently characterized as a music industry outsider, Meek actually began his professional recording career as an employee at IBC, the largest and most advanced studio in London. British engineers at that time were essentially scientists that wore white lab coats and faithfully executed procedures developed to record sounds with the greatest possible fidelity, while producers sporting suits made all of the creative decisions, despite rarely understanding anything about recording technology. That a mere engineer might offer creative suggestions—much less insist upon them being carried out—was unimaginable. Meek almost singlehandedly lead the revolution that ultimately toppled that regime

Between 1955 and 1957 Meek engineered dozens of hit records for major pop and jazz artists—often adding unique sonic touches that distinguished them from the recordings of their peers. To realize the sounds he heard in his head, Meek tweaked tape machines and pushed limiters to the max to get the hottest possible levels on tape, used compressors to create pumping and breathing effects, placed microphones close to and sometimes inside sources rather than in the officially prescribed positions, experimented with using the “wrong” types of microphones, and sometimes even went so far as to intentionally overload preamp inputs. Meek was also a big fan of acoustic echo chambers and tape delay, and in 1957 he built his mysterious “black box” spring reverb unit out of a broken heater to get even more ambient effects (several years before the development of the Accutronics spring reverb unit). It is also likely that Meek was one of the first engineers to direct inject (DI) the electric bass.

The implementation of these techniques resulted in a major paradigm shift that has now become almost universal. British pop recordings made in the 1950s incorporated a lot of room sound. Microphones were typically placed well away from sources, and separation was achieved by keeping the musicians far apart from each other. Meek close-miked sources, largely eliminating the room sound, and then used compressors and limiters to tighten up those sounds and give them more punch. To compensate for the lost ambience, and sometimes to create unnatural ambient effects, Meek would send entire mixes to an echo chamber. He might also add tape delay—using a three-head reel-to-reel recorder—and it is quite possible that he was the first person in England to delay signals beforerouting them to an echo chamber, thus inventing pre-delay.

While many producers bristled at what they perceived as Meek’s challenges to their authority, because so many of his recordings became hits, other producers refused to work with anyone else. For the same reason, Meek became the engineer of choice for numerous artists and record companies.

Trad-jazz trumpeter Humphrey Lyttelton’s “Bad Penny Blues” is one of the best-known early examples of the way Meek’s approach changed the character of recordings for the better. The song was built around a boogie-woogie piano bass line and pushed along by a snare drum played with brushes. Meek compressed all the instruments far beyond what was usual for jazz recordings, but he also made the brushes prominent in the mix and intentionally distorted the piano bass line.

“It was Joe’s concept,” said the late Denis Preston, who produced the session. “He had a drum sound, that forward drum sound, which no other engineer at that time would have conceived of doing, and with echo. And Joe created this at a time when I was being told that the rhythm section should be felt and not heard. He was the first man to use what they then called distortion. I know what they call it now—now they build it into gear! And that made a hit out of what would otherwise have been just another track on a jazz EP. It was purely a concept of sound.” “Bad Penny Blues” made it into the Top 20 on the pop hit parade.

While at IBC, Meek also experimented with sound-on-sound recording using two recorders. “Joe and producer Michael Barclay used to work with what they called ‘composites,’ which they made track by track by track,” said the late engineer and producer Adrian Kerridge, who worked with Meek at the time. “What they were in effect doing was multi-track recording using the composite method. Nobody else to my knowledge in London, in fact, in Europe—I don’t know about America—was working this way at that time.”

Despite those many successes, Meek eventually grew tired of the confines and often adversarial environment of IBC, and left in September of 1957. A few months later he helped Preston found Lansdowne studio and before long Kerridge joined them. Meek designed a 12-channel mono tube mixer with EQ on every channel (a luxury at the time), which he had custom built by EMI/Hayes. Meek also installed EMI TR50 and TR51 recorders and oversaw all of the studio’s technical arrangements. The engineers at IBC called Lansdowne “The House of Shattering Glass” because of its clarity of sound, and in 1959 it became one of London’s first stereo studios. Meek remained there until November 1959.

Meek also built two more of his fabled black boxes while at Lansdowne. One was a Pultec-style equalizer described by one of its owners as “probably the warmest, smoothest, most transparent equalizer ever made.” Another was a Langevin-style compressor/limiter. Meek left both units at Lansdowne when he departed. He took his third black box—the spring reverb—with him. According to Kerridge, “It worked very well, and Joe was very secretive about it. To my knowledge, this was probably the first spring reverb unit of its kind. It produced a very twangy and reverberant sound that he used to great effect on many of his recordings.”

Additionally, Meek appears to have invented tape flanging during that same time—an effect usually presumed to have been developed in the 1960s. According to Kerridge, Meek used two tape machines to produce the effect circa 1957. “It was very successful and we used it a lot.”

During the Lansdowne years, Meek was also making impressive recordings at his tiny Arundel Gardens flat, most notably his “Outer Space Music Fantasy” called I Hear a New World, a full-length album that was recorded in stereo. How Meek managed to work in stereo remains a mystery, as nobody who was there recalls seeing any stereo equipment. The largely neglected recording is interesting because it provides fascinating insights into how an early audio innovator working at the dawn of commercial stereo dealt with issues such as phase relationships, imaging, and the juxtaposition of dry and processed sounds. Beyond that, Meek’s use of signal processing, tape manipulation, and tape loops puts the record in a class by itself. (Note: the commercially available CD release of I Hear a New World contains a drastically altered version of little historical significance.)

Despite his many extraordinary accomplishments in the 1950s, Meek is best known for the records he made in the 1960s, which were recorded in his legendary home studio located on the third floor above a leather shop in London at 304 Holloway Road. The 11×12 control room had no direct view of the roughly18x14 recording area down the hall, and Meek had to run back and forth between the two rooms to communicate with the musicians. Also, while the sound of an echo chamber can be heard clearly on nearly every recording made at 304 Holloway Road, and Meek claimed to have one, he very likely used the bathroom for that purpose.

As to what gear Meek used when making his classic 304 Holloway recordings, including “Telstar,” it ranged from professional quality to homemade, and as is the case with most studios the gear was continually being upgraded. For example, when Meek started out his main recorder was a modified Lyrec TR16-S, which he used along with a couple of portable EMI TR Series machines—but a few years later his recorders included an Ampex Model 300, an EMI BTR2, and several auxiliary machines. And it was much the same with his outboard gear, microphones, etc. But, even if it were possible to determine exactly what he was using on a particular session, that wouldn’t necessarily offer much insight into getting “the Joe Meek sound,” because he modified practically everything that he owned.

As Meek’s gear evolved, so did his approach to recording, which always involved combining multiple tracks in various ways. In November of 1962, he recorded himself walking around his studio describing his gear and the way he used it. Here’s an excerpt:

“The main machine is a Lyrec twin-track. I usually record the voice on one track and the backing on the other. The other recorder is an EMI TR51. This I use for dubbing. The artist has his microphone, a Neumann U 47, in the corner of the studio, screened off from the rest of the musicians. He’s going on a separate track [of the Lyrec]. The bass is fed in direct, the guitars have microphones in front of their amplifiers, and the drum kit has two or three microphones placed around it. Then, I dub the artist’s voice on again. I listen to the tracks that we’ve already got … Sometimes they’re good enough, but as a rule, the vocalist wears headphones and the track is played back to him, and it’s dubbed onto my TR51. So we have voice and rhythm tracks.”

Note that Meek does not record the voice onto the second track of the Lyrec, as he had the guide vocal cut at the same time as the rhythm track. Instead, he mixes it in real time with the rhythm track from track one of the Lyrec, straight to the EMI TR51, saving a generation of track bouncing. Peter Miller and Ted Fletcher, who both were recorded by Meek at different times, describe modified versions of this basic technique, devised by Meek after he had acquired additional professional recorders.

Meek was extraordinarily prolific and although his three most celebrated records are John Leyton’s “Johnny, Remember Me” (this revolutionary 1961 “death disc” is arguably Meek’s greatest recording), the Tornados’ monumental hit “Telstar,” and the Honeycombs’ “Have I the Right?” from 1964—Meek made a huge variety of records from schlocky pop to psychedelic rock. There is twangy instrumental guitar music, kickass rock and rockabilly, sci-fi, orchestral, and even country and western—just to name a few. And Meek’s regular session musicians included luminaries such as guitarists Ritchie Blackmore and Jimmy Page (who credits Meek as a major influence on his own production).

On February 3, 1967, Meek murdered his landlady with a shotgun and then turned the weapon on himself. The circumstances surrounding his horrific end remain unclear—but what is clear is that everyone from home recording enthusiasts to celebrity engineers and producers owe something to Joe Meek whether they are aware of it or not.

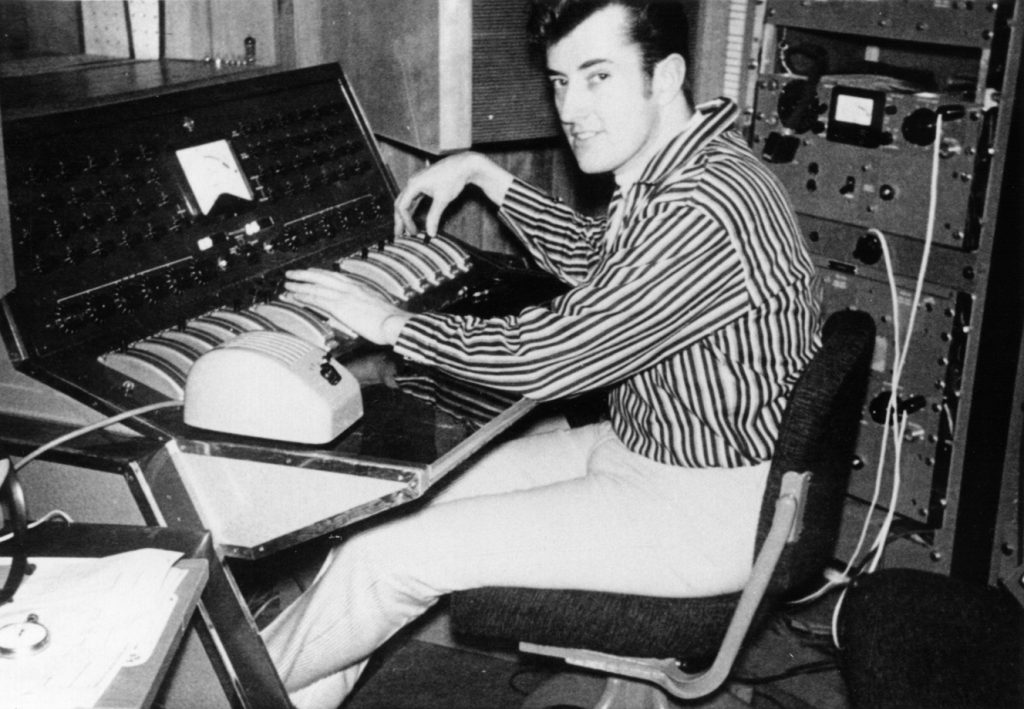

Main Photo: John Pratt, Getty Images.

IBC Photo courtesy Denis Blackham.

Lansdowne Photo courtesy Chris Williams, supplied by John Repsch.

304 Holloway Road Photo: David Peters.

Barry Cleveland is a Los Angeles-based guitarist, recordist, composer, music journalist, and editor-in-chief of Model Citizens and The Lodge, as well as the author of Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques and a contributing author to Stompbox: 100 Pedals of the World’s Greatest Guitarists. Barry also served as an editor at Guitar Player magazine for 12 years and is currently the Marketing Communications Manager at Yamaha Guitar Group. barrycleveland.com

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

I would love to know where I may purchase this Book….Joe Meek Bold Technique along with his CD.

Thank you,

KK DARLING

kkdarling1@gmail.com

https://www.amazon.com/Joe-Meeks-Bold-Techniques-Hardcover/dp/B00SB1GUS6

Hi there! Enjoyed reading this so much. Thank you for sharing 🙂