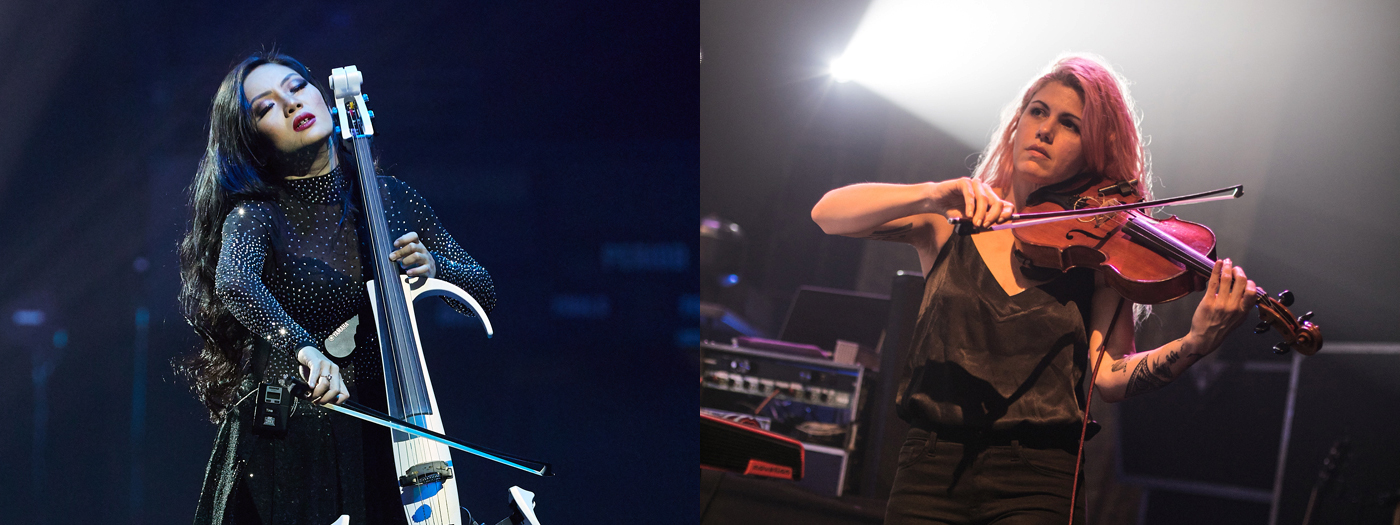

Not Guitar: How Tina Guo & Lisa Molinaro Make Cellos and Violas Rock with Line 6 Effects

by James Rotondi

In her video for “The Rains of Castamere,” from the Game of Thrones soundtrack, noted cellist Tina Guo—one of film composer Hans Zimmer’s go-to string players on soundtracks from Gladiator to Wonder Woman to Dune, and a huge concert attraction in her own right—looks more like some fierce Far East warrior princess than an unprepossessing classical and djent music fan. The same might be said for violist Lisa Molinaro, whose moody, evocative string work in Modest Mouse, as well as The Decemberists, The National, and her own Talk Demonic might suggest a blonde-streaked indie-rock diva, but whose far-reaching background in both modern classical and popular forms is paired with a decidedly down-to-earth demeanor.

What both women share is a desire to stretch the boundaries of their instruments beyond their traditional roles, even as they honor—and in Tina’s case, continue to regularly perform with symphonies—the chamber and orchestral greats, from Mozart to Elgar and beyond. For Guo, who plays her Yamaha SVC-210 electric cello through a Line 6 Helix LT, and Molinaro, who plays an acoustic viola through Line 6 M9 and HX Effects processors, the challenges and joys of using effects for strings are markedly different than they are for guitarists. That difference extends to technique, touch, and yes, taste. Still, given their naturally emotive sound, strings have a way of blooming mightily with the textural, atmospheric potential contained in Helix.

As Molinaro puts it, “I always want the listener to go somewhere else in their mind and heart, and to enjoy a kind of journey, and when you’re listening to a song with strings and effects, it’ll can really do that.”

You both studied classical technique and repertoire growing up; when did the rock bug bite, and what were the first bands that made you begin to think, “Can I make my instrument sound like that?”

Tina Guo: Well, my parents are both music teachers: mom’s a violin teacher, and dad is a cello teacher. And we literally weren’t allowed to listen to anything else but classical growing up. In my late teens, though, I managed to listen to some cassettes of Marilyn Manson, Guns N’ Roses, and Rammstein, and that’s where the dream came from of wanting to sound like an electric guitar—in my case, industrial metal guitar, specifically. When I was in college, I bought my first electric cello at the Guitar Center in Hollywood, spent two years sounding terrible on it, with various pedals, and eventually began to find a way to play what I was hearing in my head.

Lisa Molinaro: As a kid, I was sort of moving between viola and piano as my two primary instruments. My Dad was a musician, and he was playing keyboards and singing in rock bands, so we had a pretty diverse musical environment at home: lots of Motown, acid rock, and classical. Ironically, my first cassette was also Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction; I used to hide it so my mother couldn’t see the album cover. But like Tina, it took me a long time to sort of figure out how I was going to bring my classical training together with my love of hardcore punk. I mean, I wanted to thrash around, play on my knees, all that stuff. But it wasn’t until I moved to Portand, Oregon in my twenties that I started playing with a pickup on my viola, got a Voodoo Lab Proctavia, and began actually doing it.

What were the challenges you both noticed right off the bat? In what ways did you quickly realize that playing guitar through pedals and amps was decidedly different from playing a chamber instrument?

Lisa: Even at my first gig with Talk Demonic, there were issues. I mean, the FOH guy didn’t know how to deal with my sound, and he wouldn’t really let me deal with my own sound either! And of course, there were feedback issues. Unlike Tina, I’ve never played an electric viola; it’s always just been my acoustic one. Now, if you have a pickup on a resonant acoustic instrument, and you have these other loud instruments onstage like drums and amps, that’s all going to vibrate through your viola, and cause feedback. In a sense, that forced me to start EQing even before I really knew that it was called EQing! But y’know, once I got my first distortion box—a Voodoo Lab Proctavia—and learned how to roll off certain frequencies, I started to hear how it could all be done, that the viola could sound different than it’s supposed to, and that I could finally bang my head now!

Tina: For me, since I bought that electric cello, feedback has not been much of an issue. And I very much differentiate between the acoustic and the electric cello. It’s very Jekyll & Hyde for me, and I still play a lot of classical concerts, so I think of them probably much the same as you would electric and classical guitar. One is like the alter-ego of the other. For my electric cello, I used an amp and individual pedals for a good ten years before I was introduced to the Helix platform by a great live engineer named Igor Stolarsky, who also happens to be a Senior Embedded Systems Engineer at Line 6.

I was using the Coffin Case BDFX-1 Blood Drive pedal—which is the one pedal I’ve hung onto since going with Helix—and other pedals with an ENGL Fireball amp, but the pedalboard and amp were just incredibly heavy, and I’d have to hire a separate tech just to help me with all that. Igor brought a Helix over to my place, and though I really only use five or six main patches, which Igor helped me dial in, I was converted pretty quickly. I use the Helix LT with Hans Zimmer Live, and it’s so light, compact, and great-sounding. I don’t use anything else anymore.

Lisa: The precursor to the HX Effects I have is an M9, which I’ve got right here in front of me. Guitarist Johnny Marr from The Smiths had played in Modest Mouse for a while, and he came and visited and jammed with us one day in Portland, and actually gave me his M9. He just said, “You’ve got to try it. It’s really amazing. You can do all this cool stuff with it.” That was my first foray into having a multi-effect processing unit, and I never stopped playing it from that day. With the M9, I could now set up different effects “scenes,” which allowed me to be more adventuresome in my playing with both Talk Demonic and Modest Mouse, and get a little crazier with sounds even while refining it all a little more. The sounds I had used with Modest Mouse were generally a little more traditional, in a sense, using reverbs and delays. But with the M9, songs, I started to use harmonizers and the delays to stack pitches and create sort of mini-chamber-group sounds, with octaves, minor thirds, fifths, whatever would work for the song.

What are some of the amp and effect blocks that you find yourself returning to?

Tina: I have two main amp choices that I like for my live work: one of them is the Jazz Rivet, which is like a Roland JC-120 Jazz Chorus amp; and the other is the Angl Meteor, which is like my old ENGL Fireball 100 amplifier, and gets me that very metal sound I like to have. When I work on soundtracks, I like to have four main distortion tones, including things like the Brit Plexi Jump, and this is so that I can cover a range of frequencies. Often in soundtrack work, you can be dealing with something like 200 layers, and you have to find where the cello can sit in all that. I always send four different distortion tracks, plus a dry signal, for the composer/producer so they can choose what works best in the track.

Lisa: I use a few different amps, but it’s the delays and reverbs that I probably focus on more. I really like the Simple Delay and the Euclidian delay on the HX Effects: the Euclidian basically breaks up the delays into a series of slices, and the rhythms change as you tweak them. I also like the Glitz reverb, which is a bit like a Strymon Big Sky Bloom, and the Ganyemede, which is a really great Hall reverb. For distortions, I still tend to think Fuzz is the best choice for the viola, so I go for things like the Arbitrator Fuzz, the Tycoctavia Fuzz, and those more Hendrix-y pedals. I think those types of sounds are great for bowed instruments.

I’m very curious how using distortion impacts the way you play a stringed instrument. On guitar, using overdrives and distortions is what allows us to play very sustained notes, and thus to create a kind of lush legato sound. But cellos and violas are built to do that already. How does it work?

Lisa: Well, that’s interesting you say that, because it’s kind of the opposite for us. With distortion, I’m generally just bowing no more than four inches out from the “frog,” which is the end of the bow that I hold, and where you tighten the bowstrings. So, just the low end of the bow. Your attack has to be really “grabby” if you want it to track well, to pick up the sound and process it without it all getting muddy. You want to go in pretty hard, and things like double-stops work really well because of that. I have to say, I just don’t do rapid passages that often with Fuzz.

Tina: It’s actually a lot more forgiving to play the electric cello with effects as opposed to an acoustic instrument. With an acoustic cello, I feel like you’ve got a lot more details and nuances which need to connect all the time. With distortion, for sure, if I’m trying to get those heavy, chunky sounds, I also play really short, hard notes with the bow, to the point where, a lot of the time, I’m literally hitting and beating the cello with the bow. If the distortion was turned off, it would sound terrible! As far as faster passages, it’s much the same: I have to play very, very short bow strokes—even shorter than what we normally think of as staccato—in order for it to sound reasonably clean. At times, I’m literally just barely hitting the string!

Photo of Tina Gou: Suzanne Teresa

Photo of Lisa Molinaro: Brandon Nagy

Learn more about Helix LT: https://line6.com/helix/helix-lt.html

Learn more about HX Effects: https://line6.com/hx-effects/

Learn more about M9: https://line6.com/m-series-effects-pedals/

Guitarist and writer James Rotondi has been a Senior Editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, a contributor to Rolling Stone, JazzTimes, Acoustic Guitar, Mojo, and Spin, and has toured with the acclaimed bands Mr. Bungle, Humble Pie, and French electro-rock group Air. He lives in Nashville.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

The first fuzzed Cello I’ve heard decades ago was Tømrerclaus’ Cellokarma from 1978

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hK9Euy1HhZo