Reeves Gabrels – Is Art-Rock’s Jedi Master Really a … Blues Rocker?

by James Volpe Rotondi

Owing to his brainy, maze-like runs and otherworldly textures, guitarist Reeves Gabrels has been dubbed a “Jedi Master” in the press more often than he can count. A longtime member of post-punk pioneers The Cure, decade-plus collaborator with David Bowie, former touring guitarist for Paul Rodgers, and a prolific bandleader in his own right, the 65-year-old Gabrels certainly merits the honorific. So when his tattoo-artist son-in-law was authorized by Lucasfilm to create official Star Wars tatts, the 65-year-old naturally opted for the distinguished “Grey Jedi” crest.

In his solo playing, too, Gabrels can be seen as a kind of interstellar sensei, skilled with both mind and sword. (Or in his case, a Reverend Reeves Gabrels Signature guitar with signature RG Railhammer pickups.) Gabrels’ jazz-fueled Jedi training ripened at the esteemed Berklee School of Music in the ’70s, but his basic training took place in venues like the Fillmore East, at the feet of bluesy rock heavyweights like Leslie West, Steve Marriott, and Michael Schenker—players who relied more on the force in their guts than the figures on any scale diagram.

That said, Gabrels knows his Lydian b7 from his altered scale, and he’s not afraid to wield either, especially when those tonal colors are allied with the fresh, vivid, and often alien guitar sounds that have become his session signature over the last three decades.

We caught up with Gabrels at his home studio “lair” in Upstate New York where, in the interest of his ever-more-surprising tonal palette, he keeps a wide assortment of vintage amps and guitars, pedals, and Line 6 gear—from an original DL4 Delay Modeler to the M5, M9, and M13 multi-effectors, and a recent model Helix Floor and HX Stomp. It’s quite the sonic force. “The thing about the Grey Jedis,” says Gabrels, “is that they don’t believe the Force is necessarily good, but they also don’t believe it’s necessarily evil. The force just is. It’s all in how you use it.”

We reflexively think of you as this kind of avant-garde rock player, but in fact, you grew up on many of the same ’70s blues-rock idols as many of your peers. What’s the connection there?

Everybody in my little circle in Staten Island when I was in seventh and eighth grade back in the early ’70s were all Leslie West fans. I remember getting home from school in January of 1971 and there was a storm coming, so I got out of school early. At that point in my life, I wanted to be a comic book artist. So, I’m sitting at my desk drawing, and I’ve got the radio on—I had just discovered “open format” FM radio. The legendary DJ Scott Muni was on, and it was like someone had brought him The Gnostic Scriptures or something; it was a test pressing of the brand new Mountain record, Nantucket Sleighride. I mean, he did everything but read the catalog number. Listening to that album was a revelatory moment for me. It’s as if everything I’ve continued to love in life grew out of that moment: dark, stormy weather, Les Paul Juniors, and this whole span of “progressive blues-rock,” for lack of a better expression.

This will be a revelation for many players out there, too, many of whom are more likely to identify you with, say, the Downtown New York avant scene, or more fusion-type influences.

I used to get really annoyed when I would get lumped in with Richard Lloyd, Robert Quine, and Marc Ribot—the Downtown guys. All great players, and I share a lot of their aesthetics and even some of the harmonic things. But if you peel all that away, I was putting a pretty big fat rock tone out there on the guitar, with pretty good finger vibrato. In the early Bowie days, I used to get really frustrated that people couldn’t see the difference between me and the Downtown guys.

My roots are in 1970s English and American rock: Leslie West, Peter Frampton, Ollie Halsall, Neil Young, Steven Stills. I was a big Michael Schenker fan, too, which makes sense, given the kind of tones I like, and because he was like Leslie West, but faster and louder. Where I’ve ended up tonally is probably a sum of Schenker, Ronson, and Leslie West. I mean, in 1975 I had been in New York City for a good two years going to art school, and I had a rock band called Malice that started out as a cover band on Staten Island, playing Mountain, Mott the Hoople, Bowie, Spooky Tooth, and Humble Pie. Then I started taking lessons from John Scofield after I had seen him with Billy Cobham and George Duke’s band. It was Scofield who basically talked me into going to Berklee.

Scofield said, “You know all the rock guitar tricks. So now you’ve got to listen to trumpet, listen to what horn players do and how keyboard players use their left hand. For all the things you’re asking about and all the things you want to know, you’d be much better served to just go to Berklee, because for you to get what you want from me is going to take 20 years of lessons, but you go up there for a couple of years and you’ll get it all.” He was right. I really wanted to know how to “talk” to other players that weren’t playing guitar. I wanted to have a common language with all musicians.

Two things that really identify your playing are your use of the whammy bar while you play lines—not necessarily just at the end of them—and your tendency to leave little unresolved blue notes at the end of a phrase. You don’t like to go for stock phrases, do you?

My feeling is that the music you make should change based on the day you’ve had, and it should be informed by the life you’ve lived. Melody is always going to be the last frontier, because you’re putting your heart on the line. When you play a melody you’re saying to people, “I think this is beautiful.” Anytime you present something you think is beautiful to people you don’t personally know, well, you’d better have some seriously thick skin. So, while I do use the whammy bar a lot, every time I’m in a position where the music doesn’t ask for it, I step away from the whammy bar. And I step away from it to remind myself that melody is the last frontier.

As to your question about the unresolved quality of many of my lines and

chords, you might find it interesting that my favorite resolution chord is a

Major 7 #11, and that I usually like to play it with some distortion. Look,

life is never fully resolved, y’know? You may get some resolution at different

points in your life, or get acceptable resolutions you can live with, but

there’s always that little bit of uncertainty. It’s exactly like playing the Major

7th chord, letting it ring … and at the last moment you gently tap the #11.

That’s life.

You’re no stranger to Line 6, or to amp modelers, having been an early adaptor of the Line 6 Amp Farm plugin in the ’90s on Bowie’s Earthling, and other albums. And you’ve had a DL4 forever! Tell us about what you’re currently using to craft sounds in the studio and on the gig for The Cure and Reeves Gabrels & His Imaginary Friends.

It’s funny, but my grab-and-go pedalboard still has my old DL4 Delay Modeler and the MM4 Modulation Modeler on it. In fact, I’ve got two DL4s and an M5 on my Cure board. The M5 is really handy for some of the earlier Cure stuff, because back then a lot of the time the reverb was being driven into overdrive or an overdriven amp. Now, that’s a sound! [Read Jeff Schroeder on the Virtues of Running Delay and Reverb Before Distortion] A very hard, hard reverberation. So I actually keep the M5 earlier in my signal chain, before my distortions. I’ve got a G2 GigRig switching system, as well, so I don’t have to worry about buffering issues. I’ve got at least ten settings on the M5 just for the songs from the first three or four Cure albums alone.

Hell, I still drag my Line 6 M13 with me to the studio all the time, because when people want me to come into the studio, they want me to make cool sounds. If they want it to sound like Keith Richards, they know other guys that can do that. At some point, I had to accept the fact that I had become a known quantity as a stylist—but the good news was that I was a known quantity! I use the Helix Floor a lot for recording at home and for sessions, though I have not used it in a live setting yet. I feel that I really need to know a piece of gear inside and out before using it on the gig. I also have an HX Stomp which I’m getting to know better, but again, not really ready to take out for a tour.

Let’s talk sounds and blocks: what are some of your go-to modules and presets?

Generally, I’ll find an amp that I like, and build a pedalboard around that. I pretty much treat Helix like I would treat creating a rig if I was setting it up in the analog world, and that’s because, at age 65, I still view the world through an analog lens. One of my go-tos is the Brit P-75 Nrm, which, though based on a Park 75, is one of my favorites for kind of a Marshall Plexi crunchy rhythm sound. I’ll pair that with a 4×12 Blackback 30 cabinet block, which is basically me mimicking my live rig, because I use Vintage 30s all the time, sometimes pairing them with CreamBack 65s.

Another go-to is the amp block called WhoWatt 100, and that’s basically a Hiwatt Custom DR103. For a long time, I was using three Hiwatt D103s with three 4×12 cabinets with The Cure [laughs]. It may surprise some people, but The Cure is an incredibly loud band. My volume on stage is around 104 decibels coming out of the cabinet. For my rhythm volume! Boosted up 5db for solos, I can literally feel my trousers vibrate against my skin.

There’s also a preset in Helix called Space Cadet which I’ve modified quite a bit. It starts with a Deluxe Comp compressor, then a Low Cut/High Cut EQ, a Looper, followed by a Particle Verb, Octo reverb, and Cave reverb. I use this setting for a lot of my textural stuff. I also like the Tycoctavia Fuzz block a lot, and I’ve noticed I’ve been using the Bit Crusher distortion quite a bit, too. Something that gets a lot of use as well is the Octi Synth. One thing I found pretty consistently is that the blocks and the sounds that I like best are the ones that say Line 6 Original. It’s almost always the Line 6 versions that I gravitate to. That really surprised me.

Like Schenker, West, and Ronson, you’ve got a great knack for finding those parked-wah-style midrange bands that really cut through.

I’ve found that I keep going back to the Boss Graphic EQ pedal, which I had modified so it’s a little quieter. That lives in front of my SIB Varidrive pedal, which I tend to run pretty overdriven and distorted. But I control that amount of gain with my Ernie Ball Volume pedal, which was modified by the guys at Thru-Tone. Also, the Railhammer pickups on my signature Reverend Guitars do have a pronounced central midrange, and it’s a really narrow band—which also makes it easy to pull out if you’ve got a graphic EQ.

But yeah, I almost always have an EQ/boost of some kind, like the JHS Prestige booster/buffer pedal I’ve been using recently, and another one made by Thru-Tone FX in Nashville. And for those parked wah sounds, I’ve been using the Chicago Iron Parachute pedal, which is basically a reengineered Tychobrahe Parapedal, a parametric-based wah. I mean, this thing produces frequencies below the audible range, so when you bring it out of the heel down position, it sounds like it’s throwing up, and at the volume we play, I have to imagine some people in the back of the arena are having trouble holding their bowels!

So, you were an art school kid and studied art and graphic design at the Parsons School of Design and School of Visual Arts in New York City. What elements of your art training do you think show up in your tone crafting?

I guess I do think of it as almost like cartooning, or painting, and that could be the art school influence. I might think, “Is this going to be photo-realism, or am I going to go for super-realism?” You know, you might see a painting done with acrylic paint, and if you step ten feet back from it, it’ll look just like a photograph. But if you step right up to it, three feet away, you’ll see all the brushstrokes. I tend to look at sound that way.

Look, it’s just a matter of how refined your taste is, and how far into the technique of something you want to go. Brush strokes in a painting may look unfinished to most people. But people that have actually used a brush, well, they like to see the brush strokes. It’s the same with musicians. Being a creator of music or art is a weird position to be in because you have to be able to simultaneously wear the hat of the average listener, the hat of the dilettante artist, and the hat of another creator. The question becomes, “Who do you want this piece of work to speak to?”

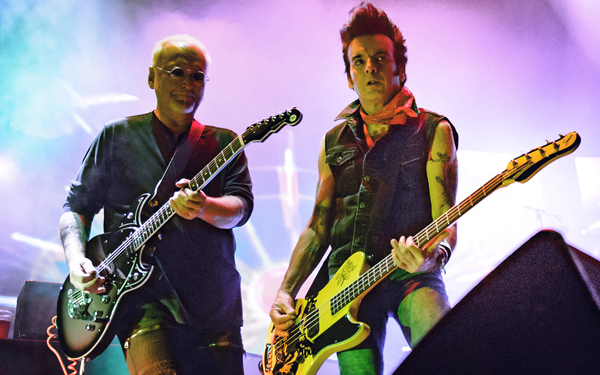

Photos: Mauro Melis

Learn more about Helix: https://line6.com/helix/helix.html

Learn more about M Series Pedals: https://line6.com/m-series-effects-pedals/

Guitarist and writer James Volpe Rotondi has been a Senior Editor at Guitar Player and Guitar World, a contributor to Rolling Stone, JazzTimes, Acoustic Guitar, Mojo, and Spin, and has toured with the acclaimed bands Mr. Bungle, Humble Pie, and French electro-rock group Air. He lives in Nashville.

Related posts

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Thanks for the post !! Like you the Line 6 originals are the ones I go to the most on my POD GO (coolest little modeler ever!!!)…..tweaked the comet trails filter effect so that it swells with the notes and has a ‘bubbling’ sound on low notes ….crazy !!!