Chris Gill: Nashville’s Dirty Secret – Country Music’s Founding Forefathers of Fuzz

by Chris Gill

The raspy, buzzy, square-wave distortion effect that guitarists know and love as fuzz is associated mostly with various misfit genres of rock and roll, including garage rock, psychedelia, the British invasion, punk, indie, and grunge. From the mid-’60s sounds of the Count Five’s “Psychotic Reaction,” the Strawberry Alarm Clock’s “Incense and Peppermints,” and the biker movie soundtracks by Davie Allan and the Arrows through the fuzz-saturated riffs of Nirvana, the Melvins, and Mudhoney in the ’90s and today’s garage/blues rockers like Jack White, Dan Auerbach, and Gary Clark Jr., fuzz has earned a reputation over the last five decades as an effect beloved by a more rebellious breed of rockers.

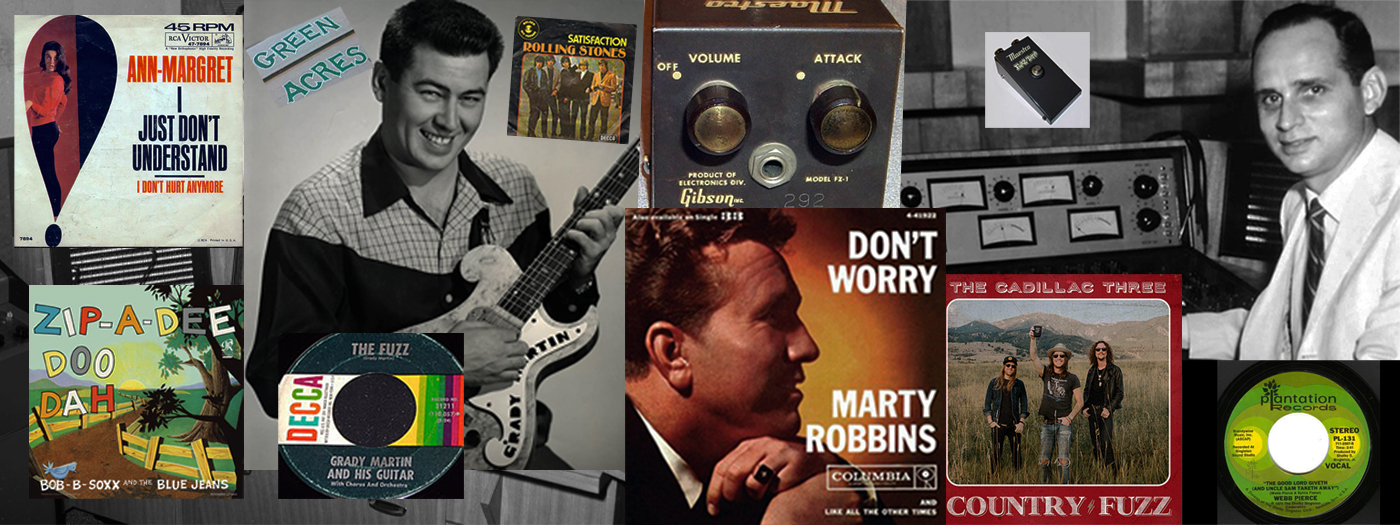

The earliest examples of fuzz that casual popular music fans are aware of include the Rolling Stones’ “Satisfaction” and the Yardbirds’ “Heart Full of Soul,” both released in 1965, while a few music history aficionados with deeper knowledge will cite the Ventures’ 1962 single “The 2,0000-Pound Bee (Parts 1 and 2)” as the song that started it all. However, the true birth of fuzz goes back a few years even before that, originating from the unlikely source of Nashville’s recording studios and a variety of country guitarists and artists who embraced this revolutionary new sound. For about a five-year period before the Stones recorded “Satisfaction,” fuzz guitar was featured on dozens of country singles, and the sound remained a vital, if often overlooked, element of country guitar vernacular well into the late 1970s.

While blues, rock, and rockabilly guitarists increasingly embraced distorted tones during the ’50s and purposely abused their amps by damaging speakers or loosening tubes to generate distortion, the discovery of fuzz was made completely by accident. During a session at Nashville’s Quonset Hut Studio in late 1960 for Marty Robbins’ single “Don’t Worry,” engineer Glenn Snoddy failed to notice that a transformer blew in the recording console channel that was being used to record a 6-string bass part performed by session guitarist Grady Martin. When Martin began to play his solo about a minute and a half into the song, the bass produced a raspy, heavily distorted tone. Robbins and producer Don Law liked this novel, new sound and decided to keep the heavily distorted 6-string bass track as-is.

Shortly after “Don’t Worry” was released on February 6, 1961, it became a big hit, spending ten weeks at #1 on the Billboard country singles chart and peaking at #3 on the pop singles chart. Wisely, Snoddy set aside the malfunctioning channel strip for future use in case anyone asked him to replicate the sound. In January 1961, just prior to the single’s release, Grady Martin revisited this new signature sound, making it the centerpiece of his instrumental single “The Fuzz,” which most likely is where the effect’s name originated.

Soon Snoddy was receiving more requests for the “fuzz” sound than he could accommodate, so he collaborated with his friend Revis V. Hobbs, an engineer at WSM Radio, on building a standalone device that could replicate the distinctive “fuzz” distortion. Together they came up with a compact transistor-based circuit housed in a small metal box with a footswitch that allowed users to activate the effect when desired. Snoddy pitched their invention to Gibson, which introduced the device as the Maestro FZ-1 Fuzz-Tone in 1962.

The next notable country single featuring the fuzz sound was “I Just Don’t Understand” by Ann-Margret. Recorded May 9, 1961, at RCA Victor Studio B in Nashville, the single was produced by Chet Atkins and featured Billy Strange on guitar. Allegedly, the session engineer created Strange’s fuzz guitar tone by overdriving the input channel’s preamp on the recording console. Later in 1962, Strange recorded additional fuzz guitar tracks for “Zip-A-Dee-Doo Dah” by Bobb B. Soxx and the Blue Jeans and “The 2,000-Pound Bee” by the Ventures, using a homemade fuzz box made by country pedal-steel guitarist Red Rhodes for the latter.

Dozens of country artists recorded songs featuring fuzz guitar over the next few years. By 1965, when Los Angeles studio guitarist Tommy Tedesco was recording his parts for the theme to Green Acres, fuzz guitar had become such an accepted part of the contemporary Nashville sound that he opted for the effect instead of the traditional twang of a Telecaster or Gretsch. The sound of fuzz became even more prevalent on country singles over the next few years, with memorable tracks released by Ferlin Husky, Wanda Jackson, Waylon Jennings, Buck Owens and the Buckaroos, Jimmie Rodgers, and the Willis Brothers.

Fuzz continued to be a fixture of country guitar tone throughout the Seventies, but the number of recordings that prominently featured the sound began to dwindle by the end of the decade. Some of the better-known examples from this period include “The Runnin’ Kind” by Merle Haggard, “The Good Lord Giveth and Uncle Sam Taketh Away” by Webb Pierce, and “T For Texas” by Charlie Walker.

The current sounds of country music have progressed and changed dramatically over the years, but now could be a great time for open-minded country guitarists to explore the tones and textures of fuzz once again. The Cadillac Three is a great example of a current country band that embraces heavily distorted guitar tone—in fact they love raunchy square-wave distortion so much that they named their latest album Country Fuzz. Thanks to them and a handful of like-minded up-and-coming bands, fuzz is poised for a strong country comeback.

Chris Gill is the former editor-in-chief of Guitar Aficionado and a regular contributor to Guitar Player and Guitar World magazines. He is an avid collector of dusty effects pedals, obscure American, British, and Japanese amps, and useless trivia about music and instrument history.

Related posts

By submitting your details you are giving Yamaha Guitar Group informed consent to send you a video series on the Line 6 HX Stomp. We will only send you relevant information. We will never sell your information to any third parties. You can, of course, unsubscribe at any time. View our full privacy policy

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.